Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI (2024).

ISSN: 1576-3420

Received: 07/12/2024 --- Accepted: 09/19/2024 --- Published: 10/10/2024

INTERTEXTUALITY BETWEEN LITERATURE, CINEMATOGRAPHY AND EDUCATION: THE STRATEGIC NARRATIVE PATTERN IN THE ART OF WAR AND GAME OF THRONES

INTERTEXTUALIDAD ENTRE LITERATURA, CINEMATOGRAFÍA Y EDUCACIÓN: EL PATRÓN NARRATIVO ESTRATÉGICO EN EL ARTE DE LA GUERRA Y JUEGO DE TRONOS

![]() Alfonso Freire-Sánchez: Abat Oliba CEU University. Spain.

Alfonso Freire-Sánchez: Abat Oliba CEU University. Spain.

![]() Maria Fitó-Carreras: International University of Catalonia. Spain.

Maria Fitó-Carreras: International University of Catalonia. Spain.

![]() Montserrat Vidal-Mestre: International University of Catalonia. Spain. mvidalm@uic.es

Montserrat Vidal-Mestre: International University of Catalonia. Spain. mvidalm@uic.es

How to cite this article:

Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria, & Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat (2024). Intertextualidad entre literatura, cinematografía y educación: el patrón narrativo estratégico en el Arte de la Guerra y Juego de Tronos. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1-24. http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2024.57.e887

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Sun Tzu's Art of War, a book on war strategy, is considered a source of inspiration for cinematography in the field of strategic management, as numerous films inspired by its precepts are used as didactic examples in universities and business schools. Objective: This paper analyzes Sun Tzu's work and its intertextuality between literature, cinematography and education. Specifically, it investigates whether the Game of Thrones series captures the strategic axioms of the work and whether these can serve as a narrative pattern. Methodology: To do this, the content analysis of the series is combined with the literary analysis of the book to compare the war narrative of the series with Tzu's axioms. Results: The results allow us to contrast the existence of a certain strategic narrative pattern that guides the interrelation between the different fields: from literature to cinema and from cinema to consolidated theories on strategic management. Discussion: The treatment of heroism differs considerably; however, there are intertextual elements such as the need to manage human and material resources, the use of deception and spies, and the importance of elements and terrain. Conclusions: The narrative war pattern of the series inherits intertextual elements that, over the course of time, have evolved into established theories on business strategy derived from the axioms or strategic principles of The Art of War.

Keywords: The art of war, Sun Tzu, Game of Thrones, strategic narrative, intertextuality.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Art of War, written approximately 2,000 years ago by Sun Tzu, a military man and philosopher, is considered “the world's most influential book on strategy, and is passionately studied today in Asia by politicians and executives, just as it has been by military leaders and strategists for millennia” (Cleary, p. 7). Similarly, “there is evidence that it has been considered a direct or indirect influence on countless leaders, military leaders and thinkers of all cultures and times” (Freire-Sánchez, 2022, p. 105). The work has not only survived throughout this time, it has also transcended the military and political sphere: “it is studied in marketing and advertising companies, in coaching seminars, in the large technology companies of Silicon Valley (Steve Jobs was another of its great readers)” (Aranda, 2023, p. 19).

Thus, the teachings of master Sun Tzu have been included in the world of business and business management (McNeilly, 1999; Scott, 2007) and marketing (Silva, 2016). Similarly, they have been used to study human behavior and social psychology (Ashrafian, 2015) as well as labor relations and personal and professional success (Chu, 2009). Similarly, it has been reproduced in various media and formats such as video games (Jiménez-Alcázar, 2014) or cinema (Chang, 2020).

This study has been motivated precisely by the representation of the principles that make up The Art of War in cinematography, specifically those axioms that are embodied in the war narrative of the series Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019). In view of the pedagogical value of cinematography (Chang, 2020) as a tool to exemplify and teach business management models (Sweeney & Hughes, 2017) or business ethics (Teays, 2017), it has been considered relevant to reflect on and confront the intertextuality existing between literature, cinematography and education between the series Games of Thrones and the approaches and validity of Sun Tzu's millenary work.

The work of Sun Tzu has been chosen as a counterpoint to the Game of Thrones series, based on five main criteria. Firstly, because of its high war and strategic content. Secondly, for being one of the most watched and popular series of the 21st century (Ross, 2019). Thirdly, for being one of the most awarded and valued productions of the last decades according to specialized portals such as IMDb or Rotten Tomatoes. Fourthly, for being used as pedagogical audiovisual material in universities and business schools (García-Tojar as cited in Guerra, 2019). And, finally, for being based on a novel, so it shares a literary origin with The Art of War.

In 1996, they published Game of Thrones, the first of the seven books that make up the A Song of Ice and Fire book series, written by George R.R. Martin. This epic fantasy saga chronicles the decline of the monarchy in the imaginary kingdom of Westeros and its Seven Kingdoms, as well as the conflicts of war between seven influential families seeking to seize the Iron Throne. In 2011, HBO adapted the book into a series whose budget was unthinkable for television, and which has now become a standard (Ross, 2019). The production consists of a total of 73 episodes, divided into 8 seasons, released between 2011 and 2019.

1.1. The analogical validity of The Art of War in the field of business management and strategic management

Therefore, why should one continue researching on a millenary work? In the same way that Tugores and Bonilla-Quijada (2020) propose a re-reading of David Ricardo's economic principles from the prism of the present day, a similar analysis of the validity of Sun Tzu's axioms in the field of business strategy and management according to the specialized literature follows.

To this end, Chen (1994) relates the theory of competitive advantage in the market, among other strategic concepts, to the teachings drawn from the work of Sun Tzu. Similarly, in 2005, Robert Scott (2007) proposes an analogy between the Taoist philosophy that permeates the work of the Chinese master and the so-called samurai spirit to propose a decalogue on business management. In parallel, Moon (2018) develops an analysis of different business strategies, comparing the theories of Porter and other economists with the axioms derived from Master Sun. Cesarin and Balbo (2020), for their part, propose The Art of War as an analogy to the technological war that, according to the authors, China is waging against other world superpowers. On the other hand, Hlavatý and Ližbetin (2021) consider that the ideas embodied in The Art of War can be applied today insofar as they provide business executives with the necessary guidance for strategic decision-making. For these authors, one of the benefits of the work is that it is “a clear and comprehensive method that combines political and economic strategy, team-building rules and business competence” (p. 1,273). The study on the review of the most studied theories on strategy carried out by Oliveira and Ferreira (2021), who consider The Art of War as one of the most consulted works even today, also stands out.

Regarding the question about the validity of the millenary work in the entrepreneurial and business field, Jaime Silva (2016) considers that “the entrepreneur who seeks to constantly analyze the objectives of his/her business and develops strategies under Sun Tzu's point of view, will be able to face the war with much more tranquility and wisdom” (p. 6). In contrast, for Sha (2018), the ideal is to combine the principles of Sun Tzu's philosophy with current mathematical methods (or software) to obtain information and that will reduce the time needed for calculations and studies on the market and big data. In this sense, Samuel van Deth (2020) in his essay The Art of War & Sales: Is Sales the Next Frontier for the Bots? not only states that The Art of War is current, but also that this work can be applied to the field of sales in that it uses similar terminology and that sales tries to defeat its rivals, as happens in war. Xinrui and Mohd (2022) also advocate the validity of the teachings derived from the axioms of Sun Tzu's work, and even suggest that they can be used as a guide to develop effective Corporate Social Responsibility strategies.

Therefore, according to the specialized literature, it is possible to affirm that, even with certain nuances and logical adaptations due to the secular passage of time, The Art of War can be considered a suitable and valid means to explain theories and strategies in university classrooms and business schools. Therefore, if the results show that there are parallels in these marketing precepts between Sun Tzu's work and Game of Thrones, the series, or at least some excerpts from it, could be used to explain in the classroom concepts on strategy derived from the millenary work.

1.2. Cinematography as an educational tool on marketing, business models and business management

The very marketing, promotion and distribution of films and series can be considered a didactic example of marketing strategies and business models. So much so that Dupont and Augros (2013) assert that the relationship between business strategy and film is not a by-product or an afterthought of the film industry, but an integral part of film production and the movie-going experience. But, from the point of view of audiovisual storytelling, the use of films and series in the educational context as didactic and pedagogical tools has been the subject of study for decades. These audiovisual resources are recognized for their high capacity to enrich learning (Chang, 2020), offering a diversity of perspectives, audiovisual examples and results that can be described as multifaceted.

Integrating cinematography in the classroom facilitates a more dynamic and participatory educational scenario. This allows an in-depth exploration of complex topics through an accessible and stimulating format for students, solving one of the problems pointed out by Richards and Pilcher (2018) such as the limitation of literacy, based solely on texts when teaching subjects that involve emotions and empathy or highly subjective concepts such as strategy. Below, as an example, Table 1 lists some films that have reproduced elements related to business management or cases of business strategy failure and success.

Table 1.

Main cinematographic titles as a pedagogical tool in business strategy and management.

|

Titles |

Pedagogical implementation |

|

Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) |

Pursuit of power. Impact of greed. |

|

Pay it Forward (Capra, 1946) |

Ethics, integrity and responsibility in scenarios of financial adversity. |

|

Seven Samurai (Kurosawa, 1954) |

Leader's charisma to motivate and achieve objectives. |

|

Network (Lumet, 1976) |

Manipulation and the power of the media. |

|

Wall Street (Stone, 1987) |

Impact of greed in the business environment. |

|

Apollo 13 (Howard, 1995) |

Crisis resolution (organization, coordination, listening, decision making). |

|

Jerry Maguire (Crow, 1996) |

Loyalty, integrity and customer service. |

|

Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg, 1998) |

Strategic decisions in the battlefield, ethical dilemmas and resource management. |

|

The Social Network (Fincher, 2010) |

Entrepreneurial spirit and ethics, people management, and persistence and flexibility in growth strategies. |

|

The Wolf of Wall Street (Scorsese, 2013) |

Business ethics, emotional intelligence, power and leadership. Fraud and business success stories. |

|

Draft Day (Reitman, 2014) |

Decision making under pressure. Importance of maintaining principles and bargaining power. |

|

The Big Short (McKay, 2015) |

Market analysis, business risk and strategy in decision making. Fraud and success cases. |

|

Jobs (Stern, 2015) |

Leadership, entrepreneurship and business strategies. |

|

The founder (Hancock, 2016) |

Business expansion: franchising and marketing strategies. |

|

Air (Affleck, 2023) |

Market research, marketing strategies, business risk and decision-making strategy, success stories. |

|

Society of the Snow (Bayona, 2023) |

Resource management, ability to adapt to adverse situations and ethics in decision making. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Likewise, the consequences of the use of film in the classroom as a pedagogical and educational example are multifaceted and complex and cannot always be considered positive. This is precisely one of the contributions made by Hugo Letiche and Jean-Luc Moriceau (2019) in their work Turn to Film: Film in the Business School, considering that films offer opportunities for learning and research, but can also be sources of ideological poison, self-deception and misrepresentation. Kesimli (2023), for his part, argues that film has been inspired more by big corporate scams than by good business, so it would be a useful tool for teaching what not to do, while Chang (2020) asserts that the use of films and series in business schools is still very much in its early stages, but it is clearly a growing trend. Chang (2020) also argues that, faced with the saturation of impacts and multimodal information, education professionals should take advantage of other tools such as film to teach any content or theory.

Moriceau et al. (2022) in their article Des films pour relier: introduire les affects dans la business school (Films to engage: Introducing affects in business school), put forward four premises that cinema possesses and that make it a useful medium or tool in university studies and business schools. First, the authors speak of its ability to oppose original narrative and univocal meaning as it tells stories in a variety of ways: “the narrative thread (fable) describes the sequence of actions and circumstances, revelations and changes; the image (opsis) counteracts this thread, challenges it, speeds it up or slows it down, and enriches it with a range of meanings, aesthetic pleasures and affects” (Moriceau et al., 2022, p. 50).

Another characteristic proposed by the aforementioned authors is that film forces reflection, as it “affects, proposes new perceptions, speaks directly to the body, expels routines and refrains and forces us to think” (Moriceau et al., 2022, p. 50). To these ends, Kresse and Watland (2016) see the use of films in the classroom as a means of creating shared experiences, as well as the opportunity to foster small group discussion. Similarly, researchers Verstraete et al. (2018) also point out that the complex and multidisciplinary nature of film makes films a useful teaching material to use in the classroom. Thirdly, film allows relating what is perceived with abstract ideas or thoughts, giving rise to emotions and sensations that do not necessarily need to be experienced personally but through the seventh art (Moriceau et al., 2022) This thought maintains parallels with that previously raised by Tyler et al. (2009) on the beneficial fact that it is beneficial to include films or fragments of these in classes with the aim of fostering real-life connections with the course content.

The last characteristic in this regard is that cinema is a means to fight against uniformity and imaginary standards, to surprise through the unexpected and to seek paths towards self-determination. For Moriceau et al. (2022), this is an opportunity “to reflect on this uniformity and standardization, on the film industry and its effects on subjectivities, and to challenge what still works in us, what we still know how to desire and our possibilities for individualization” (p. 50). Below, (see figure 1), an infographic is proposed which summarizes the main characteristics of the use of cinematography in the classroom, according to the above-mentioned research:

Figure 1

Infographic on the impact on the application of cinematography in classrooms.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

1.3. Intertextuality between literature and film through narrative patterns

Starting from Kristeva's (1978) principle according to which all texts are constructed as a mosaic of influences and quotations, being absorption and transformation of other subsequent texts, transforming or subverting previous stories and genres. Therefore, it is logical to think of the existence of constant intertextuality between cinema and literature. Genette (1982), for his part, provides a more systematic approach to analyzing how texts connect and transform each other and thus extends the framework constructed by Kristeva. Similarly, Barthes, in his essay The Death of the Author (1977), suggests that it is the readers who construct the meaning of the text through their experience and knowledge of other texts. He offers a framework for understanding how narratives are constructed from other narratives. More recent studies, such as those by Kuryaev and Osmukhina (2018), reflect on the mutual enrichment that occurs between literature and filmmaking, as the former seeks new ways of developing plot and constructing textual space, while the latter explores new ways of interpreting stories and developing a verbal layer of the film-text.

With respect to this vision, cinema can be considered as a mirror of cultural imaginaries and traditional stereotypes, as in the case of the virtuous and Aristotelian hero defined by Sánchez-Escalonilla (2002) and which follows the traditional narrative pattern of Joseph Campbell's monomyth or hero's journey, expanded by other authors such as Robert Mckee or Christopher Vogler. This monomyth is based on the precept that most stories, tales, legends or myths are based on the same narrative patterns and great themes of humanity, which have been reproduced in literature, cinema and other cultural media over the decades.

Although there is currently a strong tendency not to follow the narrative pattern of the hero's journey in favor of more anti-heroic and imperfect characters that break this traditional mythology and represent a more human and realistic side of society (Freire-Sánchez & Vidal-Mestre, 2022), the intertextuality and interaction between these two art forms is constant, as well as the constant adaptation of literary works in film productions. This intertextual approach promotes the fusion of genres and experimentation with the artistic form, thus generating a web of references and connections between diverse texts and discourses (Daniyeva, 2020).

2. OBJECTIVE

To this end, the following research question (R.Q.) has been posed: What parallels and analogies exist between The Art of War and Game of Thrones and what intertextual strategic axioms between the two works are useful as a tool to explain the fundamentals of strategy and decision making? Several directly related hypotheses emerge from this research question. The first hypothesis, also raised in other previous studies such as those of Arkhangelsky and Novikova (2023), raises the possibility that transmedia intertextuality is a useful tool for education as it helps to deconstruct fields of study, foster reader creativity, and enhance engagement with classical texts through various media. In this sense, it is interesting to reflect on the transmedia connections and convergences that occur between the two works. While the second hypothesis considers that transmedia intertextuality applied to teaching encourages collaborative work and active participation. This hypothesis is related to the studies of Torres-Martín et al. (2022) and those of Thrower and Evangelista (2024), although they have not focused on specific cases such as Games of Thrones and The Art of War.

3. METHODOLOGY

For this purpose, a research design with a qualitative approach is proposed which combines the analysis of film content (Call, 2019; Domínguez-Delgado & López-Hernández, 2017) with the literary analysis of the work. The first technique allows us to understand the messages, emotions and reflections of a film or series (Brylla, 2018), with the purpose of reflecting on the different episodes that make up the series Game of Thrones, especially those moments that concern strategic decisions of an eminently military nature and the actions or tactics deployed on the battlefield by the different sides and factions that are part of the plot.

Subsequently, a comparison is made with the literary analysis of Sun Tzu's The Art of War. According to Hébert (2022), literary analysis is not satisfied with describing things as they are commonly described but complements with other approaches and fields. Thus, the analysis is conducted from the discursive paradigm that has as its ultimate goal the “study of the conditions of the interpretability of texts at a given time and in a given place” (Maingueneau, 2018, p. 8). Such construability allows an analysis that evades temporal distances between works and, by addition, conceives intertextuality, as it enables an investigation to determine the way in which a narrative establishes connections and interrelates with other texts (Daniyeva, 2020).

In terms of content and methods, the series was analyzed by watching it in its original version and by using notes made by the researchers through the streaming platform HBO during the year 2024. As for the work, three versions have been used: the 2023 reprint by Ana Aranda of the classic The Art of War by Sun Tzu from the Ariel Quintaesencia publishing house, the 1999 version by Thomas Cleary entitled The Illustrated Art of War by Sun Tzu from the EDAF publishing house and The Art of War by Sun Tzu published by the Dojo publishing house in 2018.

Finally, among the three versions, it has been decided to give priority to those of Cleary and Aranda, since both have been widely commented on. Aranda's version stands out for its contemporaneity, providing a translation adapted to the current contexts of leadership and strategy, with comments that enable the connection of Sun Tzu's teachings with contemporary business and social challenges. In turn, Cleary's (1999) version is enriched with additional information, including illustrations related to Sun Tzu's writings and helping readers visualize how the tactics described are applied in different scenarios. In contrast, the Dojo publisher's choice is limited to compiling Sun Tzu's axioms, without including additional commentaries by other authors. This selection criterion meets the objective of offering an updated and comprehensive perspective that keeps intact the original purist view of Master Tzu's teachings.

4. RESULTS

The Art of War is structured in 13 chapters, each of which can be considered a strategy itself (Hartanto & Agustini, 2020). The first of these, called Strategic Assesments, lays the foundations that define much of the thinking and military actions of the work. Master Sun's first axiom is: “Міlіtагу асtіоп іs important to the nation — it is the ground of death and life” (p. 59). This premise is the plot axis of the Game of Thrones series, insofar as the narrative seed focuses on the seizure and control of the kingdom, specifically the Iron Throne and the Seven Kingdoms. So much so, that this is the starting point of the different factions or noble houses such as the Targaryens, the Lannisters or the Baratheons. With the exception of the House Tyrell, the leaders of the different lineages have been consecrated as military experts: Robert Baratheon, Rhaegar I Targaryen or Tywin Lannister, among others. Therefore, both works are based on the same concept, which is to win and gain power over rivals.

Beyond the main approach, Sun considers that to win on the battlefield it is necessary to make use of five fundamental elements: “the way; the weather; the terrain; the leadership and discipline” (p. 60). In the series, these elements are constant in the development of the actions. On the one hand, earth and knowing what path to follow are cardinal points both in the sea battles of the army that Stannis Baratheon starts against the defense of the capital city of the seven kingdoms, King's Landing, led by Tyrion Lannister, as well as in the fortress of the sea army of the Greyjoys against other land armies. Likewise, the Battle of the Bastards is an example where terrain and position play a key role, as Ramsay Bolton uses the terrain to enclose the forces of Jon Snow and the wildlings. Similarly, the weather is another fundamental element that is used by the Night's Watch to defend the Great Wall of Westeros and Castle Black from wildling incursions, and also as an element of attrition for Stannis Baratheon's troops during the long sieges of the Lannister strongholds.

Regarding command and discipline, in general, in the HBO series they go together, because so strong is an army depending on the strength and charisma of the leader, so an army commanded by Jon Snow feels unbeatable against armies with leaders who do not inspire their troops as the Boltons. The same happens in the retreat to his quarters in the midst of the battle of King Joffrey Lannister, and that meant the breaking of the ranks of the army and the disbandment of some soldiers. The series makes a distinction between armies that follow a leader and are disciplined, such as the Unsullied, versus other armies that are not very disciplined, formed by mercenaries or thieves, such as the different troops that make up the House Greyjoy. From this perspective, there are still parallels between the two works.

Doing Battle stands as the name of the second chapter, highlighting as a main axiom the following text: “When you do battle, even if you are winning, if you continue for a long time it will dull your forces and blunt your edge” (Cleary, 1999, p. 77). The importance of logistics and resources becomes evident at several moments in the plot, such as, for example, during the prolonged Siege of Meereen, where patience and resource management play a determining role in the final outcome. The serial narrative understands the wear and tear that constant conflict puts on the troops, both for the physical state and the morale of the armies, so resource management must be always imperative and not just in times of disadvantage.

In the third chapter, Planning a Siege, Tzu states that “the general rule for use of the military is that it is better to keep a nation intact than to destroy it. It is better to keep an army intact than to destroy it” (Cleary, 1999, p. 89). In this regard, Daenerys Targaryen's ability to lead and win the loyalty of conquered peoples, including the Dothraki and Unsullied, shows the importance of clear and decisive leadership in military and political success. “If you outnumber the oponent ten to one, then surround them; five to one, attack; two to one, divide” (Cleary, 1999, p. 96). Indeed, the series demonstrates that those armies that destroy the defeated enemy or burn and raze the conquered cities, instead of the defeated peoples and troops adhering to their cause, usually perish. Even if they do not destroy the enemy, they will be subjected to constant betrayals and attempts at revolt, as happens on several occasions to Daenerys in her phase of Breaker of Chains and Mother of Dragons. Therefore, at this point there is a certain paradox and the series does not follow this precept of the millennial work.

Regarding the importance of order and strategy, Sun Tzu believes that “order and disorder are a matter of organization; courage and cowardice are a matter of momentum; strength and weakness are a matter of formation” (Cleary, 1999, p. 128). The Battle of Castle Black demonstrates how Jon Snow and the Night's Watch use their knowledge of the Wall to defend themselves against a numerically superior army. But Jon Snow himself, when leading a siege as in the Battle of the Bastards, demonstrates few strategic skills, being guided by momentum, bravery and courage, even though that may mean the sacrifice of hundreds of men. From this perspective, the series demonstrates the value of strategy, as in Rob Stark's armies, but, in the end, the great battles are won by the resilience, strength, courage and bravery of their leaders or by ignominious forces such as dragons or Valyrian fire, leaving strategy in the background or on the side of the defeated.

As for the principle that “a military force has no constant formation, water has no constant shape: the ability to gain victory by changing and adapting according to the oponent is called genius” (Cleary, 1999, p. 147). This principle became very popular at the beginning of the 21st century through a BMW advertising campaign that used an old interview with actor and martial arts expert Bruce Lee. In the campaign, Lee talks about the resilience of water and ends his testimony with the phrase “be water, my friend”. In Game of Thrones, there are many characters who are highly adaptable to situations, such as Arya Stark when she loses her sight and must face an enemy that surpasses her in strength, physical condition and height. But, in particular, Jon Snow is the character who must constantly adapt his military tactics as happens in the Battle of the Bastards, showing an ability to respond to extreme and changing situations.

One of the less popular strategies in The Art of War is deception: “a military force is established by deception, mobilized by gain, and adapted by division and combination” (Cleary, 1999, p. 154). However, deception is a commonly used tool in Game of Thrones, as can be seen in the Battle of Blackwater, in which Tyrion uses a ship full of Valyrian fire to destroy the enemy fleet, or when Arya Stark uses disguise and deception to confront her enemies. In parallel, Daenerys Targaryen's surprise attack on the Greyjoy fleet and ambush of the Lannister army illustrate the effectiveness of surprise and deception as a military tactic in the series' narrative. Likewise, two of the most powerful and intelligent characters in the series, Varys and Petyr Baelish, base their entire strategy on deception and the spy network.

Regarding spies, for Master Sun: “to fail to know the conditions of opponents because of reluctance to give rewards for intelligence is extremely inhumane, uncharacteristic of a true military leader, uncharacteristic of an assistant of the government, uncharacteristic of a victorious chief.” (Cleary, 1999, p. 219). In Game of Thrones there is a large network of spies, especially in terms of advisors to the ruler who holds the Iron Throne. The narrative of the series, as well as of the novels it influences, greatly enhances the power of information and secrets, as it can be seen in the fact that a Master of Whisperers position exists, and that this is one of the main positions of power and influence in King's Landing. The character who stands out the most for the strategic use of espionage is Varys, known as the Spider and who, at some points in the plot, holds the aforementioned position. Varys uses a network of spies, who are essentially orphans, to gather all kinds of information. This information allows Varys to know everything that happens in the different kingdoms and to select what information he wants to share with those around him so that they can make strategic decisions about it. The spies that Varys uses are those that Tzu classified as natives, while other characters that use the network are Littlefinger or Tyrion, who uses his cousin as a spy, which Tzu classifies as an internal spy.

For the Chinese general “In military matters it is not necessarily beneficial to have more strength, only to avoid acting aggressively; it is enough to consolidate your power, assess opponents, and get people, that is all”. (Cleary, 1999, p. 184). Several characters use cunning over ruthless force. For example, Sansa Stark and Petyr Baelish's use of political strategies and alliances enables them to achieve their goals without the need for open conflict. However, there are also clear examples of the opposite, for example, Stannis Baratheon makes the mistake of underestimating both his enemies and the challenges of the environment, leading to his defeat and death. This fact reflects the importance of correctly assessing one's strengths and weaknesses in relation to the enemy, as well as avoiding the wasting of material and human resources and the demoralization of the troops. Likewise, political maneuvering in the series often has as much or more importance than physical battles. The manipulation and political gamesmanship of characters such as Cersei Lannister and Tywin Lannister exemplify how war is not always fought on the battlefield. Similarly, the formation of alliances, often unstable and complex, are part of the military strategies of the series, such as, for example, the alliance between Daenerys Targaryen and the Lords of Westeros, and the union of the Northern houses to confront the Boltons.

“When the generals cannot assess opponents, clash with much greater numbers or more powerful forces, and do not sort out the levels of skill among their own troops, these are the ones who get beaten.” (Cleary, 1999, p. 188). This idea is reflected in several characters, but particularly in Tyrion Lannister. His ability to understand the enemy's limitations as his own limitations allows him to maneuver successfully in complex political and military situations. Similarly, Sun believes that “rulers should not go to war in anger, commanders should not battle out of wrath. Act when it is useful; otherwise, do not.” (Cleary, 1999, p. 217). This capacity for temper and adaptability are elements that Arya Stark displays in her journey of revenge and personal growth and is, in turn, what ultimately allows her to survive and achieve her goals. The main axioms and their parallels between the two works are listed below (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of Sun Tzu's axioms with Game of Thrones.

|

Sun Tzu |

Game of Thrones |

|

Strategic Assessments |

|

|

“Міlіtагу асtіоп іs important to the nation — it is the ground of death and life” |

Battle of the Bastion of the Hand (S.2, Ep. 9). Battle of Blackwater (S.2, Ep. 9). Battle of Winterfell (S.2, Ep. 10). Battle of the Bastards (S.6, Ep. 9). |

|

Elements of warfare (the weather, the terrain, command and strategy) |

|

|

“Know the enemy and know yourself, and your victory will never be endangered; know the weather and know the ground, and your victory will then be complete.”

“Victory is achieved in the planning room, long before the battle.”

“Swiftness is the essence of war.”

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

|

Constant narrative about the threat of winter weather. House Stark's motto is “winter is coming”. Snowstorms and sudden weather changes.

Planning for the Battle of the Bastards ( S.6, Ep. 9). Preparations for the expedition to the Wall ( S.7, Ep.6).

Strategic advantage thanks to the speed of Daenerys' attack with her dragons (S.7, Ep 4).

Cersei Lannister avoids a battle with the explosion of the great Baelor sept (S.6, Ep. 10). |

|

Logistics and resources when doing battle |

|

|

“When you do battle, even if you are winning, if you continue for a long time, it will dull your forces and blunt your edge”. |

Food shortage at the siege of Stanis (S2, Ep. 9). Shortage of vidriagon weapons in the battle of Winterfell (S8, Ep. 3). |

|

Planning a Siege (strategy of attack) |

|

|

“If you outnumber the oponent ten to one, then surround them; five to one, attack; two to one, divide; equal conditions, share; at a disadvantage, stay alert; in danger, retreat.”

|

Jon Snow surrounds his enemies in the Battle of the Bastards. Stannis Baratheon divides his army. Jon Snow's Strategic Retreat ( S.6, Ep. 9) |

|

Variations in Tactics |

|

|

“A military force has no constant formation; water has no constant shape: the ability to gain victory by changing and adapting according to the oponent is called genius”. |

Jon Snow's change of strategy in the middle of battle (Battle of Bastards, S. 6, Ep. 9). Cersei Lannister goes from collaborating in the fight against the white walkers to betraying (S. 7, Ep. 7). |

|

Topography |

|

|

“ Terrain is the key to war. Don't despise it, don't underestimate it.” |

Strategic use of the mountainous land in the Battle of Bastards (Battle of Bastards, S.6, Ep. 9). Chains on the river in the Battle of Blackwater (S.2, Ep. 9). Ambush in the river in the Battle of the Fords (S.1, Ep. 9). |

|

Fire attack |

|

|

“Fire should be used only as a last resort. If it is possible to win without launching fire, that is preferable. One should always look for ways to avoid unnecessary destruction.” |

Daenerys' dragons attack Baratheon's fleet at Dragonstone with fire (S.7, Ep. 2). Valyrian fire in the battle of Blackwater (S.2, Ep. 9). Fire for the destruction of the great Baelor sept (S.6, Ep. 10). |

|

On the use of spies |

|

|

“The art of war is based on deception.” |

Main characters who carry out espionage: Arya Stark, Lord Varys and Qyburn. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

5. DISCUSSION

Although many parallels have been found between the film adaptation of George R. R. Martin's work and The Art of War, both differ from each other in the fundamental principle of intentionality. First of all, Sun Tzu's work is strategic in nature, the main premise “is not war, but peace, and one of the main axioms is to learn to win battles without fighting, thanks to strategy” (Freire, 2022, p. 105). In this sense, Cleary also highlights that Japan's resurgence after the Second World War is due to: “one of the maxims of Sun Tzu's classic work: 'It is best to win without fighting'” (1999, p. 7). Also, for Oliveira and Ferreira (2021), Sun Tzu's work is characterized by the importance of avoiding bloody conflicts and achieving victory through strategy can be considered the strategist's greatest success.

However, Game of Thrones has a clearly warlike tendency (Stavridis, 2019) which causes those characters who start from an eminently peaceful stance such as Syrio Forel, Arya Stark's swashbuckling teacher, or eminently diplomatic characters such as Lord Eddard 'Ned' Stark, to be doomed to death and disgrace. In the same way, female characters such as Sansa Stark or Daenerys Targaryen, who at first live outside the military framework and war strategies, are forced to become great strategists without scruples in order to survive their enemies and their own wounds. In this regard, there is a fundamental schism between the two works, as one seeks to avoid war through strategy and the other leads the protagonists towards a determinism based on war, violence and death.

Another aspect in which works and series differ is the heroic nature of the leaders. For Sun Tzu, the leader's worth is based on five pillars: intelligence, honesty, humanity, courage and severity. However, these attributes, which, in part, respond to the Aristotelian virtue of traditional heroes (Sánchez-Escalonilla, 2002), are diametrically different from the kings and leaders of the Great Houses of Game of Thrones, such as Joffrey Lannister, who might lack all of them, or Robert Baratheon, who lacked some of them. Most of the characters who hold leadership roles in Game of Thrones are built with attributes closer to villainy or, at best, share characteristics with contemporary antiheroes, such as extreme violence, thirst for revenge, arrogance or lack of mercy (Freire-Sánchez & Vidal-Mestre, 2022). These traits are evident in characters such as Cersei Lannister, whose leadership is based on fear and manipulation, or Stannis Baratheon, whose rigid morality leads him to make extreme decisions such as the sacrifice of his own daughter. Both examples reflect the type of leadership that, according to Sun Tzu, is destined to fail due to the inability to adapt to circumstances and to inspire genuine loyalty among the followers.

Probably the only leader who possesses the attributes that determine a good general -according to Sun Tzu- is Jon Snow, such as wisdom, honesty, humanity, courage and discipline. A highly significant fact since he is considered a bastard with no birthright to rule, Jon repeatedly demonstrates an ability to earn the respect and loyalty of his people through acts of bravery, prudent strategic decisions, and leadership putting the collective welfare before his own personal power. This narrative construction of Jon Snow also aligns with what Northouse (2018) describes as transformational leadership, a concept in which leaders are geared toward the development and motivation of their followers or team, appealing to higher values and creating a shared vision that guides the group. Jon's more heroic vision is one of the strongholds that can be applied to business management and leadership and fully aligns with the general's honor according to Sun Tzu.

However, there are elements of narrative intertextuality between the two works, such as the need to manage human and material resources, the use of deception and spies, or the importance of the elements and land, although, as discussed above, what determines in most cases the victories in the most crucial battles of the series is not intelligence or strategy, but the courage and resilience of characters like Jon Snow or the might of Daenerys' dragons. Through examples such as Tyrion Lannister or the aforementioned Jon Snow, Game of Thrones can be used in educational settings to demonstrate how the combination of strategic and ethical attributes enables leaders to navigate complex situations and make difficult decisions, an essential skill in fields such as business management and organizational leadership. Therefore, the series, like the book saga on which it is based, is less strategy-driven than the Chinese general's millennial work, although they maintain common principles that can be applied to the teaching of business management and strategy, such as team leadership and decision-making, as McNeilly (1999) Scott (2007) and Silva (2016) have related to learning in these fields thanks to Sun Tzu's work.

6. CONCLUSIONS

After analyzing the main axioms of the thirteen chapters of The Art of War and comparing them with the war and military strategy of the series Game of Thrones, it seems that the HBO series, despite having certain parallels such as the importance of war, the management of supplies or the use of deception and the use of spies, differs in fundamental approaches to the millenary work. One of these approaches is the effectiveness of strategy, which is relegated to the background, since many of the most decisive battles or confrontations in history are not decided by complex strategic movements, but by the individual and impetuous decisions of the leaders or by the devastating power of the army, either by the dragons or by the number of troops. Likewise, those leaders who have demonstrated diplomatic skills or who have based their military actions on strategy have become the great losers of the narrative.

Therefore, and responding to the first general objective of our research, the war narrative pattern of Game of Thrones tends to place victory on the side of the bravest or most courageous and not the most intelligent or strategist, so it differs in terms of narrative construction from what Sun Tzu considers a good leader or strategist. However, this war narrative pattern does have intertextual elements that have become, with the passage of time, consolidated theories on business strategy arising from axioms or strategic principles of The Art of War, being particularly noteworthy those that refer to the strategic use of spies, deception or resource management. Thus, with regard to the second objective, the narrative does raise interesting questions about the need for research in decision-making, which would be equivalent to market research. They also attach paramount importance to the identity and reputation of leaders, sponsored by a historical construct based on the narrative and emblem of the different houses (Lannister, Stark, Baratheon, etc.).

That kind of care for corporate identity raises clear parallels with the corporate identity of companies and their reputation. Despite this, it is believed that the series could incur in certain misrepresentations if it were taken as a business pedagogical element, as it happens with other cinematographic works, as Letiche and Moriceau (2019) point out. In this sense, in addition to the aforementioned lack of effectiveness of the strategy in the success of the military maneuvers of the audiovisual work, the power of the leaders is associated with corruption, tyranny, lack of scruples and cynicism, so the seed on which these strategic decisions germinate has a negative connotation.

On the other hand, as Mamaeva (2024) suggests, transmedia intertextuality is beneficial to education, as it fosters collaboration, extends learning beyond the classroom, and creates a unified experience across platforms, which enhances the overall educational experience. In turn, according to the reflections of Pecheranskyi et al. (2023), the millennial connection between the two works could, thanks to transmedia intertextuality, transform education by encouraging the active participation of students, connecting different forms of media and creating stories that do not follow a single path. This fact enriches learning and allows educators and students to adapt more flexibly to the ever-changing media environment, providing valuable tools for navigating a constantly evolving media world. Therefore, there is a belief that this intertextuality in which different transmedia universes that can be applied to different dimensions, including education (Freire-Sánchez et al., 2023), such as the narratives that emerge from both works, facilitate the understanding of the military strategy that, as previously reflected, is suitable for application to the teaching of marketing and business management.

The constant and millenary influence of The Art of War on all kinds of later creations through intertextuality has been reflected, through intertextuality, in the Game of Thrones series as it has been in countless film productions. As if Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey were a narrative pattern or monomyth, Sun Tzu's teachings have been turned into a strategic narrative pattern that transcends temporality and sociocultural context. While certain narrative elements of the series, such as betrayal and extreme violence, may seem pejorative from an educational perspective, Game of Thrones' ability to dramatize complex conflicts and moral dilemmas provides an interesting resource for teaching critical skills in learning environments. This includes the ability to adapt to changing circumstances, understand the motivations of different actors and develop deep strategic thinking, all essential fundamentals in education and business. Therefore, the educational relevance lies in its ability to transform abstract theories of strategy into practical examples that promote reflection and active learning.

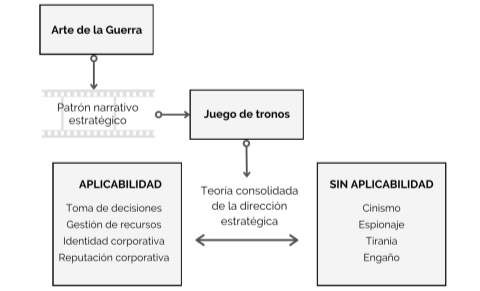

However, although this narrative pattern that converges between both works has become a consolidated theory according to the literature review carried out, in the case study, as can be seen in Figure 2, there are certain elements that are considered to have pedagogical relevance and others that, due to their eminently pejorative nature, do not have any.

Figure 2

Intertextuality, narrative pattern and consolidated theories.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

According to Kuryaev and Osmukhina (2018), there is no scientific methodology developed neither in film theory nor in literary criticism that would contribute to the competent and objective analysis and comparison of two texts, literary and cinematic. Likewise, it is believed that this type of analysis of cinematic content possesses a part subject to interpretation and subjectivity. Therefore, there is a task in the development of methodological foundations to compare the film version of literary works and their primary sources, as well as to determine the degree of mutual influence of literature and cinema.

This limitation prevents any categorical answer to the hypotheses raised, although it is believed that, as other authors have stated (Torres-Martín et al., 2022; Arkhangelsky & Novikova, 2023; Mamaeva, 2024), they are accepted insofar as they address elements that promote learning. However, the fact of approaching this intertextuality from narrative patterns and how they become consolidated theories that can be used as pedagogical elements, opens new lines of study that allow the establishment of bridges between past literary works and the contemporary cinematographic field from perspectives that have been little used.

7. REFERENCES

Aranda, A. (2023). El Arte de la Guerra de Sun Tzu. Ariel Quintaesencia.

Arkhangelsky, A., & Novikova, A. (2023). Transmedia strategies in school literary education: deconstructing kitsch and the semiotics of readerly creativity. Chinese Semiotic Studies, 19(2), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1515/css-2023-2007

Ashrafian, H. (2015). Surgical Philosophy: Concepts of Modern Surgery Paralleled to Sun Tzu's' Art of War'. CRC Press.

Barthes, R. (1977). Image-Music-Text. Fontana Press.

Benioff C. D., & Weiss D. B. (Prods.). (2011-2019). Juego de tronos [Serie de televisión]. HBO.

Brylla, C. (2018). The benefits of content analysis for filmmakers. Studies in Australasia Cinema, 12(2-3), 150-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2018.1540097

Call, C. (2019). Serial Entertainment: A Content Analysis of 35 Years of Serial Murder in Film. Homicide Studies, 23(4), 362-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767919841660

Cesarin, S., & Balbo, G. (2020). China y el arte de la guerra (tecnológica). Relaciones Internacionales, 29(59), 205-218. https://doi.org/10.24215/23142766e110

Chang, D. R. (2020). Using Films to Achieve Diversity Goals in Marketing Education. Journal of Marketing Education, 42(1), 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475319878868

Chen, M. (1994). Sun Tzu’s strategic thinking and contemporary business. Business Horizons, 37(2), 42-48.

Chu, C. N. (2009). El arte de la guerra para la mujer en el trabajo: de las zapatillas de cristal a las botas de combate. EDAF.

Cleary, T. (1999). El Arte de la Guerra Ilustrado de Sun Tzu. EDAF.

Daniyeva, M. D. (2020). Intertextuality is one of the main features of the communicative-pragmatic structure of literary works. ISJ Theoretical & Applied Science, 4(84), 844-848.

van Deth, S. (2020). The Art of War & Sales: Is Sales the Next Frontier for the Bots? Marketing Review St. Gallen, 37(5), 58-61.

Domínguez-Delgado, R., & López-Hernández, M. Á. (2017). Una perspectiva histórica del análisis documental de contenido fílmico. Documentación de las Ciencias de la Información, 40, 73-90. https://doi.org/10.5209/DCIN.56621

Dupont, N., & Augros, J. (2013). Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices. InMedia, 3. https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.625

Freire-Sánchez, A., & Vidal-Mestre, M. (2022). El concepto de antihéroe o antiheroína en las narrativas audiovisuales transmedia. Cuadernos.info, 52, 246-265. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.52.34771

Freire-Sánchez, A. (2022). Los antihéroes no nacen, se forjan: arco argumental y storytelling en el relato antiheroico. Editorial UOC.

Freire-Sánchez, A., Vidal-Mestre, M., & Gracia-Mercadé, C. (2023). La revisión del universo narrativo transmedia desde la perspectiva de los elementos que lo integran: storyworlds, multiversos y narrativas mixtas. Austral Comunicación, 12(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.26422/aucom.2023.1201.frei

Genette, G. (1982). Palimpsestos: La literatura en segundo grado. Taurus.

Guerra, A. (20 de mayo de 2019). Análisis psicosocial del final de temporada de Juego de Tronos. La Vanguardia. https://bit.ly/3XERb2x

Hartanto, F. W., & Agustini, M. Y. D. H. (2020). A Thought On Applicability Of Sun Tzu's Strategy On Marketing Strategy. Journal Of Management And Business Environment, 2(1), 38-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.24167/jmbe.v2i1.2621

Hébert, L. (2022). Introduction to Literary Analysis: A Complete Methodology. Routledge.

Hlavatý, J., & Ližbetin, J. (2021). The Use of the Art of War Ideas in the Strategic Decision-making of the Company. Transportation Research Procedia, 55, 1273-1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.07.110

Jiménez-Alcázar, J. F. (2014). El arte de la guerra medieval: combates digitales y experiencias de juego. Roda da Fortuna. Revista Eletrônica sobre Antiguidade e Medievo, 3(1-1), 516-546.

Kesimli, I. (2023). Seventh Art’s Perspective on Ethical Conduct and Corporate Irresponsibility. Springer.

Kresse, W., & Watland, K. H. (2016). Thinking outside the Box Office: Using Movies to Build Shared Experiences and Student Engagement in Online or Hybrid Learning. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, 12(1), 59-64.

Kristeva, J. (1978). Semiótica 1. Editorial Fundamentos.

Kuryaev, I. R., & Osmukhina, O. Y. (2018). Literature and Cinema: Aspects of Interaction. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 7(3), 276-383. https://doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v7i3.1621

Letiche, H., & Moriceau, J. L. (2019). Turn to film: film in the business school. Brill Sense.

Maingueneau, D. (2018). Análisis del discurso, literatura y ciencia. Arbor, 194(790). https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2018.790n4009

Mamaeva K. U. (2024). Transmedia storytelling in education. Education, innovation, research as a resource for community development, 22-25. Чебоксары: PH "Sreda". https://doi.org/10.31483/r-112269

Martin, G. R. R. (2023). Juego de Tronos (Canción de Hielo y Fuego 1). Plaza y Janes Editores.

McNeilly, M. (1999). Sun Tzu y el arte de los negocios. Oxford University Press.

Moon, H.-C. (2018). The art of strategy: SunTzu, Michael Porter and beyond. Cambridge University Press.

Moriceau, J. L., Paes, I., & Earhart, R. (2022). Des films pour relier: introduire les affects dans la business school. Management international / International Management / Gestión Internacional, 26(5), 48-60. https://doi.org/10.7202/1095467ar

Northouse, P. G. (2018). Leadership: Theory and practice (8th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Oliveira, A. J., & Ferreira, A. M. (2021). As principais tipologias estratégicas: uma revisão da literatura. Gestão E Desenvolvimento, 29, 159-176. https://doi.org/10.34632/gestaoedesenvolvimento.2021.9788

Pecheranskyi, I., Humeniuk, T., Shvets, N., Holovkova, M., & Sibiriakova, O. (2023). Transmedia discourse in the digital age: Exploring radical intertextuality, audiovisual hybridization, and the “aporia” of homo medialis. Research Journal in Advanced Humanities, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.58256/rjah.v4i2.1111

Richards, K., & Pilcher, N. (2018). Academic literacies: The word is not enough. Teaching in Higher Education, 23, 162-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1360270

Ross, I. (12 de abril de 2019). How Game of Thrones changed television. Financial Times. https://bit.ly/3zB690d

Sánchez-Escalonilla, A. (2002). Guion de aventura y forja de un héroe. Ariel.

Scott, R. (2007). El Arte De La Guerra. Las Técnicas Samuráis En Los Negocios. Robin Book.

Sha, L. (2018). Translation of Military Terms in Sun Tzu's The Art of War. International Journal Of English Linguistics, 8(1), 195-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v8n1p195

Silva, J. (2016). El Arte de la Guerra Aplicada al Marketing. IT Campus Academy.

Stavridis, J. (2019). Winning Westeros: How Game of Thrones Explains Modern Military Conflict. Potomac Books.

Sweeney, S., & Hughes, D. (2017). Integrating visual literacy training into the business curriculum. DBS Business Review, 1, 1-38. https://doi.org/10.22375/dbsbr.v1.7

Teays, W. (2017). Show me a class that’s got a good movie, show me: Teaching ethics through film. Teaching Ethics, 17, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.5840/tej20176644

Torres-Martín, J. L., Castro-Martínez, A., & Díaz-Morilla, P. (2022). Metodología transmedia en los grados de comunicación audiovisual en España. Index Comunicación, 12(2), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/02Metodo

Thrower, A. C., & Evangelista, A. (2024). Significance of Transmedia Storytelling in Higher Education: Collaborative Learning to Increase Enrollment and Retention Among Nontraditional Students. En J. DeHart (Ed.), Transmedia Applications in Literacy Fields (pp. 133-148). IGI Global. https://acortar.link/wiJTT6

Tugores Ques, J., & Bonilla Quijada, M. R. (2020). Comercio, distribución y crecimiento: una aproximación ricardiana a problemas actuales. Revista De Economía Mundial, 55. https://doi.org/10.33776/rem.v0i55.3828

Tyler, C., Anderson, M. H., & J. Tyler M. (2009). Giving students new eyes: The benefits of having students find media clips to illustrate management concepts. Journal of Management Education, 33(4), 444-461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562907310558

Verstraete, T., Krémer, F., & Néraudau, G. (2018). Utilisation du cinéma en contexte pédagogique pour comprendre l’importance des conventions dans la conception d’un business model. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat / Review of Entrepreneurship, 17, 63-89.

Xinrui, Z., & Mohd, H. B. M. N. (2022). How to Use Sun Tzu’s The Art of War to Help Businesses Fulfill Their Corporate Social Responsibility? Journal of World Economy, 1(2), 12-19. https://bit.ly/4dbE9yo

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOLEDGMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso and Fitó-Carreras, Maria Methodology: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Software: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Validation: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Formal analysis: Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Data curation: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso and Fitó-Carreras, Maria Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Supervision: Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. Project management: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Freire-Sánchez, Alfonso; Fitó-Carreras, Maria and Vidal-Mestre, Montserrat.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

AUTHORS:

Alfonso Freire-Sánchez

Abat Oliba CEU University.

PhD in Communication Sciences (UAO CEU). Award for Best Scientific Article in the 2nd FlixOlé-URJC Spanish Cinema Research Awards. Ángel Herrera Award for the Best Teaching Work (2013-2014). Attaché (AQU). He has been a member of the research team (2018-2022) of the R+D+i Project “Visibilizando el dolor: narrativas visuales de la enfermedad y storytelling transmedia” (VISIBILIZÁNDOLO). He is currently director of Advertising and PR Studies at the Abat Oliba CEU University. The results of his research have been published in Scopus, WoS and SPI. The main thematic lines are mental health narratives in the creative industry; audiovisual imaginaries and narratology.

Índice H: 9

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2082-1212

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&user=zReiVosAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alfonso-Freire-Sanchez

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57204866041

Maria Fitó-Carreras

International University of Catalonia.

Teacher and researcher at the School of Communication Sciences at the International University of Catalonia. PhD candidate in Communication. Degree in Law from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Her line of research is the study of branded content in the sound media. Advertising producer specialized in sound media. Member of the Consolidated Research Group (2021 SGR 01243) AINA (Analysis of Audio-visual-textual Narrative Identity).

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0500-4006

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&user=Md5fZQsAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria-Fito-Carreras

Academia.edu: https://uic-es.academia.edu/MariaFitó

Montserrat Vidal-Mestre

International University of Catalonia.

PhD in Communication Sciences, Master in Business and Institutional Communication Management, Master in Audiovisual Post-production and Degree in Political Science and Administration. Professor at the International University of Catalonia, Open University of Catalonia and University of Barcelona. Vice-Dean of the School of Communication Sciences at UIC Barcelona. Her line of research focuses on audiovisual, corporate and brand communication and narrative.

Índice H: 6

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6144-5386

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=YTcq2CUAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Montserrat-Vidal-Mestre

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57918972400