Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI (2024).

ISSN: 1576-3420

|

Received: 04/18/2024 --- Accepted: 07/08/2024 --- Published: 08/26/2024 |

CYBERVIOLENCE IN SPAIN: TYPES, VICTIMS AND AGGRESSORS

CIBERVIOLENCIA EN ESPAÑA: TIPOS, VÍCTIMAS Y AGRESORES

![]() Janara Sousa: University of Brasilia, Brazil.

Janara Sousa: University of Brasilia, Brazil.

![]() Nuria Rodríguez Ávila: University of Barcelona, Spain.

Nuria Rodríguez Ávila: University of Barcelona, Spain.

![]() Pilar Rodríguez Martínez: University of Almeria, Spain.

Pilar Rodríguez Martínez: University of Almeria, Spain.

This research work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation under grant PID2021-127113OB-I00.

How to cite this article:

Sousa, Janara; Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria & Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar (2024). Cyberviolence in Spain: types, victims and aggressors [Ciberviolencia en España: tipos, víctimas y agresores]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2024.57.e877

ABSTRACT

Keywords: Cyberviolence; Internet; Human rights; Women and Girls; Spain.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Esta investigación tiene como objetivo comprender la dinámica de la ciberviolencia en España mediante el análisis de noticias publicadas en el periódico El País. Se busca identificar a las víctimas y agresores más frecuentes, así como los principales tipos de ciberviolencia. Metodología: Utilizando el Análisis del Discurso, se examinó una muestra de 60 casos de ciberviolencia reportados en El País desde 2007 hasta finales de 2023. Resultados: La violencia en línea ha incrementado su presencia en España, destacando a las mujeres como las víctimas más comunes, mientras que los hombres se identifican principalmente como agresores. Los tipos de violencia observados con mayor frecuencia incluyen grooming, ciberacoso, filtración de contenidos íntimos sin consentimiento, y acosos sexual y moral. Discusión: Consistente con tendencias globales, las niñas y las mujeres jóvenes son las principales víctimas. También, se destaca el proceso de victimización de las mujeres con algún tipo de prominencia social. La discusión, además, subraya la desigualdad de género subyacente en la ciberviolencia. Conclusiones: Existe una notable impunidad respecto a la ciberviolencia en España, caracterizada por la falta de responsabilización de las plataformas digitales y una regulación estatal que aún se percibe como insuficiente.

Palabras clave: Ciberviolencia; Internet; Derechos humanos; Mujeres y Niñas; España.

1. INTRODUCTION

Spanish people recently discovered the serious damage that can be caused by artificial intelligence. What became known as the Almendralejo case resulted turned out to be a shock because of the "innovative" type of violence, which defies even Spanish law. In September 2023, at least 20 students from a school in a small, quiet Spanish town, Almendralejo, posted intimate images of almost 20 girls, aged between 11 and 17, on social networks and messaging apps. What is most shocking of all is that none of the victims had actually taken intimate images. The images of their faces were captured from their Instagram and WhatsApp profiles, and from this material, the aggressors generated deepfake, which tries to create a false image of someone. In this case, taking advantage of the girls' faces and building pornographic images with artificial intelligence.

"Detecting fake nude photographs of teenagers in Almendralejo (Badajoz) proves there is a plague of sexist violence with hyperrealistic creations of artificial intelligence for malicious purposes, especially pornographic ones, and it has reached Spain" (Limón, 2023, para. 1).

There is still no regulation in Spain, or even in the European Union, that provides sanctions for intimate content produced by artificial intelligence from images of a real person. Although confrontation measures are incipient and inconsistent, according to data from Sensity IA, 96% of the images produced by artificial intelligence are pornography without consent and women are the victims in 90% of the cases (Sensity IA, 2020). Data from the Internet Watch Foundation (2023) also show that artificial intelligence has been used to generate images of child abuse.

It is worth noting that online life is becoming much more popular in Spain. It is becoming more and more an element of the everyday life of citizens. Rather than that, it is a fundamental part of sociability, access to information, forms of communication and entertainment (Castells, 1997). In addition, it must be recognized that there has been much progress in closing the various digital divides, such as age, gender and social class (Torres, 2017). As shown in Figure 1, Spain is among the countries with the highest level of connectivity and where the percentage of connected people is quite high.

Figure 1

Percentage of people connected and time spent connected by country.

Source: Statista, 2022, https://www.statista.com/

However, the global network imposes other problems that must be prevented and confronted: online violence. Cases of this type of violence impress by their multiplicity and variety and by their exponential capacity to generate victims, aggressors and types of violence (Sousa et al., 2019). Official data from the Crime Statistics Portal of the Ministerio del Interior (2022) indicate that online violence increased by 17% in the last year in Spain. Of course, this increase must be much higher, considering that most cases are not reported to the official authorities.

Data from the governmental organization Save the Children also reinforce the problem of cyberviolence in Spain, emphasizing that, in 2019, 7 out of 10 young people had already suffered some type of violence at this level (Sanjuán, 2019). The report “Violencia de género digital: una realidad invisible” (Digital gender violence: an invisible reality), prepared by the Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital, ponders on the serious problem of online violence against women and argues that:

Just as digitalization is increasingly permeating every aspect of life, gender-based violence based on digital tools can represent a huge obstacle for victims, who may even be forced to leave the digital universe, with serious psychological, social and economic consequences. (Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital, 2022, para. 3)

The study points out that cases of cyberviolence against women have increased, especially when it comes to harassment, threats, hate speech, violation of privacy and online sexual exploitation. In particular, sexual offenses are the fastest growing. Figure 2 shows the increase in cases over time.

Figure 2

Cyberviolence victimizations: sexual offenses (absolute values).

Source: Statistical Crime Portal, Ministerio del Interior, https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico/

2. ONLINE VIOLENCE AND ONLINE GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE

Online violence, as mentioned above, is an increasingly prevailing phenomenon in the digital era, and represents a complex and multifaceted set of abuses and aggressions that manifest themselves in the digital environment (Poland, 2016). This type of violence differs from other forms as, due to the global network, it transcends physical barriers and is characterized by its exponential ability to reach individuals regardless of their geographic location, thus expanding its reach and the impact of such harmful and injurious behaviors (Sousa et al. 2019).

Online violence thus brings with it what is known as the weight of violence already embedded in our social context, i.e., it is based on an unequal power structure, where the dominant is male, white and heterosexual and which, through violence, keeps other social groups under domination (Bourdieu, 1989; Foucault, 1992).

Cyberviolence is a systemic and symbolic phenomenon. It is symbolic because it is most often materialized in the field of language and discourse, centralizing power in the hands of a few groups. Therefore, online violence, when symbolic, contributes to the perpetuation of a certain universe of meaning that naturalizes positions of power and uses language and discourse as a vehicle for it (Žižek, 2008).

Online violence is also systemic to the extent that it recovers the historical basis of violence that already pervades our social environment. In this respect, the victims and perpetrators on the Internet are the same as in our so-called "real" world (Žižek, 2008). Minority and vulnerable groups that may pose a threat to the status quo, by having a voice on the Internet, suffer abuse, aggression and persecution and are systematically censored and even silenced.

Systemic and symbolic violence contributes to maintaining power through the exercise of violence against those who wish to confront the imposed order. Regarding cyberviolence, studies indicate that the main victims are women and girls, and the aggressors are men (United Nations [UN], 2015; Poland, 2016; Lionço, 2019; Sousa, 2021; Núñez et al., 2017; Instituto Avon, 2021).

According to data from the United Nations, by 2015 more than 70% of women in the world had already suffered some type of cyberviolence (UN, 2015). Likewise, data from the Instituto Avon (2021) indicate that this percentage has already risen to 85%.

Poland (2016) points out that the very history of the internet is characterized by the prominence of white, upper-middle class, North American men. This aspect, often overlooked when discussing the history of the World Wide Web, helps to explain the prevalence of male dominance in the digital world.

Patriarchy and male domination condemn girls and women to adopt certain behaviors and ways of life through violence, whether physical or symbolic (Bourdieu, 1998). Saffioti (2001) goes on to add that men use violence on female bodies to control and subjugate them, exercising it as an additional resource for their ability to command. In the roots of Spanish culture, the traces of this phenomenon shape a sexist and misogynist Internet, in which women are not welcome.

Girls, young women and women with some kind of social, political or cultural leading role are the most attacked on the networks (Association for Progressive Communications, 2023; Sousa & Rodríguez, 2023). According to Jankowicz (2022), as a general rule, women are attacked and marginalized on the Internet, with the aim of silencing them and dissuading them from participating in public life.

Valente et al. (2016) also draw attention to the significance of naming the abuses and aggressions that occur in the digital environment as violence. Although it may seem less dangerous, cyberviolence has serious consequences that affect: "(...) physical and psychological health, educational and work opportunities, political participation, freedom of expression and movement, as well as the ability to generate narratives and online friendly spaces" (Bosch & Gil-Juarez, 2021, p. 2). Furthermore, it is important to point out that, according to the Instituto Europeo de la Igualdad de Género (2017):

experts have cautioned against conceptualizing cyber VAWG[1]as a completely separate phenomenon from violence in the "real world," when, in fact, it is more properly perceived as an ongoing trend of violence taking place offline. (p. 1)

The anonymous nature and ease of dissemination on the internet helps perpetuate abuse, harassment and hate speech, challenging traditional notions of safety and social interaction. Jon Ronson (2015), in this report book So You've Been Publicly Shamed, speaks out against the widespread capacity of the digital world to destroy reputations and lives, leading many people to social isolation or even suicide, as well as anxiety, depression, and school dropout (Bernardo et al., 2020).

The types of violence are of the most varied and make it clear that this is not only reproduction, but also production of new types of violence, which are even the reason for modification of the Criminal Code in Spain, as in the case of the Solo Sí es Sí (Only yes is yes) law (Ley Orgánica 10/2022).

Cyberviolence can take many forms, including, among others, cyberbullying[2], doxing[3], grooming[4] and the creation of a scenario of misinformation and hate, deeply affecting people's mental health, dignity and safety (Waldron, 2012). This phenomenon raises critical questions about the regulation of online behavior, the responsibility of social networking platforms and the need to promote a more ethical and respectful digital culture.

3. OBJECTIVES

Given this scenario, this research aims to observe the dynamics of cyberviolence in Spain. To do so, it highlights the types of violence, the most frequent victims and aggressors. An analysis of journalistic material related to the topic of online violence, published in the Spanish newspaper El País, from 2007 to the end of 2023, was also carried out.

4. METHODOLOGY

The phenomenon of cyberviolence lacks research and data. Official data are scarce and, in some countries, rare. In Spain, there is some official data on the phenomenon of online violence in the Crime Portal. However, despite its significance, such data is still scarce and deserves an intersectional deepening in order to understand the dynamics of cyberviolence in the country. Moreover, the wide range of types of violence that emerge and multiply makes it difficult to produce data and combat actions.

It is therefore essential to invest in research that can provide primary data and allow a better understanding of the phenomenon. It was with this objective in mind that this research focused on compiling materials published in the newspaper El País.

It is not uncommon to see cases of cyberviolence printed in the pages of newspapers. Insults, threats and humiliations against people with political, artistic and intellectual prominence are common. Newspapers tell the stories of those who survived and those who died. Stories that are often not included in the official data, but that form a representation and an imaginary about violence on the Internet.

In this regard, it is fundamental to recognize the importance of journalism in recording recent events, but it is also crucial to observe the limitations of such stories, considering that, especially in cases of violence, what is printed in newspapers only represents the tip of the iceberg.

Among all the Spanish press media, the following selection processes were taken into account when choosing the newspaper El País. The first is that, through Semrush's Open.Trends tool (https://es.semrush.com/trending-websites/es/all), it was possible to verify that the newspaper's page is one of the 20 most visited in Spain, a fact that demonstrates its importance and also its ability to reach more readers. Secondly, it is worth noting that it is a traditional newspaper that has existed in Spain for more than five decades. It also stands out for being the most widely read Spanish newspaper outside Spain.

Thirdly, it is an accessible media, as it has a print and online version. In the online version, where the material for this research was collected, most of the published material can be consulted free of charge, simply by registering on the newspaper's website.

As a fourth aspect, it is noted that the newspaper provides nationwide coverage, which makes the sample more representative of the country, bringing news that goes beyond the coverage of the cases of large Spanish cities. Finally, El País stands out for being the most widely read newspaper in Spain, with an average of almost 800 thousand daily readers of the printed version and more than 75 million unique Internet users per month, only in Spain, as evidenced by the use of Statista (https://www.statista.com/). Such figures reveal the reach of the materials published in this newspaper.

As for the criteria for evaluating the news, the collection covered the period from 2007 to December 2023. This covered from the first publications of cyberviolence cases in the first decade of the 21st century to the present day. In total, 200 materials related to online violence were collected. Materials selection was based on the objective of this research in a coherent and consistent manner.

The selection criteria for the materials to be analyzed were as follows:

a) These were news items in which focused mainly on a cyberviolence issue;

b) The news item explained in detail a case of cyberviolence;

c) The news item focused on a case that occurred in Spain.

By implementing these three filters, it was possible to form a sample of 60 news items that presented cases of cyberviolence in Spain. The identification of these cases of violence was fundamental because only from them was it possible to observe aspects of the dynamics of online violence, such as: victims, aggressors and types of violence. Finally, it is important to note that some of the materials selected for the sample featured case repercussions that developed during police investigations.

That said, it can be affirmed that the sample is sufficiently representative of the phenomenon of cyberviolence in Spain, insofar as:

- it covers a broad time span (2007 to 2023), which makes it possible to observe the evolution of cyberviolence over more than a decade;

- it includes a wide variety of types of cyberviolence, which enables an understanding of the various forms that this phenomenon can take;

- it reveals cases of violence in different regions of Spain, considering the national coverage of the newspaper El País; and, finally,

- it provides patterns that make it possible to identify, for example, characteristics of victims and aggressors.

Laurence Bardin's (2016) methodological procedure of Content Analysis was used in this work. As recommended by this method, first, a free reading and a pre-categorization were performed. At this stage, the aim was to understand the patterns presented in the selected material, such as information about victims and aggressors. It was noted that these data were sufficient to at least identify who were the most recurrent victims and aggressors, as well as the types of cyberviolence being committed. Then, work was done in two stages: the first was more quantitative and the second more qualitative, in order to carry out a methodological triangulation and analyze the phenomenon in a more complex way (Bericat, 1998).

In the quantitative stage, as recommended by Ander-Egg (1995), there was an understanding of the people and individuals who appeared in the materials under analysis. That is, it was possible to extract as much information as possible about the victims and aggressors, especially gender and age. The intention was to seek more data; however, the material under consideration highlighted little about the social players involved. Therefore, it is essential to explain that not all the contents analyzed contained all this information, so it was often necessary to search for related materials to complement the analytical framework. In addition, at this stage it was necessary to observe the frequency of the types of violence, since it had been perceived that certain types tended to occur more frequently. For this stage, metrics were also developed to evaluate the results, such as the sex and age of the victims and aggressors, as well as the frequency of different types of cyberviolence, such as harassment, threats and leaking of intimate images without consent.

As for the qualitative analysis of the content, it focused on aspects related to the victims' testimonies, which revealed how they felt about what happened and, on some cases, clarified the consequences of the violence suffered. Also at this stage, the dynamics of online violence were analyzed through a detailed study of each case. This analysis, based on the theoretical framework, made it possible to highlight phenomena such as polyvictimization and the ability of a single aggressor to victimize several people at the same time. This exhaustive analysis also provided the possibility of understanding the relationship between victim and aggressor.

This methodological design was undertaken to try to unravel some aspects of the dynamics of online violence in Spain, given that there is a profound lack of information on the subject. Methodological triangulation, or the use of mixed methods, offered the conditions to give coherence and complexity to the research (González, 1997).

Integrating the results from both stages allowed for a more complete and nuanced understanding of cyberviolence. Quantitative data provided an overview of sociodemographic characteristics and frequency of types of violence, while qualitative analysis offered a deeper understanding of underlying experiences and dynamics. This methodological triangulation allowed for the construction of a robust analytical framework, highlighting both general patterns and the particularities of each case.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To facilitate the understanding of the findings of this research, the analysis and discussion was divided into three parts, which concern the fundamental aspects for understanding violence in Spain: profile of the victim; profile of the aggressor; and the most frequent types of cyberviolence.

The evolution of cases has been exponential in recent years, the words have been online violence; cyberviolence; virtual violence. The analysis of the newspaper articles in a pleasant way can be visualized in the following cloud (see Figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Word cloud of selected headings.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the selection of articles with the program https://www.nubedepalabras.es/

Figure 4

Evolution of gross and net cases per year.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

5.1. Victims

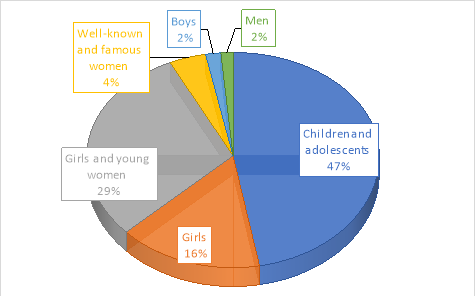

The material being analyzed revealed that the main victims are children and adolescents in general, girls and young women. In the 16 years of analysis of materials published in the newspaper El País, from 2007 to 2023, 276 victims of cyberviolence were identified. A total of 97,18% of them were women, girls and boys and adolescents whose sex could not be identified. This phenomenon can be better observed in the following chart:

Figure 5

Cyberviolence victims in Spain, during the publication period of El País from 2007 to 2023 (percentage).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

First, it should be noted that the main victims are girls and young women (Poland, 2016; Lionço, 2019; Sousa, 2021; Núñez et al., 2017). Women and girls represent more than 52% of the victims, a percentage that could be much higher, taking into account that in the group "children and adolescents" it was not possible to identify the sex of the victims, since, as mentioned above, not all the information was available in the collected materials. An example is the case of the aggressors who practiced grooming. In general, they had several victims at the same time and all of them were under 18 years of age. The aggressor in the city of Puerto Real, Cadiz, committed grooming against more than 70 children and adolescents. Complaints about this case began to appear in 2009.

The case of this stalker is also symptomatic of another finding: girls and boys are more likely to be polyvictimized, considering that the aggressor manages to hold them hostage to blackmail and threats for a longer period of time, which leads the victims to suffer a series of abuses and aggressions, including physical ones.

Given this scenario, it is possible to infer that in the group of "children and adolescents" there are many more girls than boys. In any case, it is hereby recognized that children, adolescents and young women are overwhelmingly the majority of victims in Spain, following the trend already highlighted by research from the United Nations (2015), Save the Children (2017), Instituto Avon (2021), among others.

Surely, such a situation is caused by gender inequality. As Bourdieu (1998), Saffioti (2001) and other authors rightly point out, gender violence is used to define the male's position of power. In this respect, women who are in the public arena, as well as those who benefit from the experiences of the digital world, are punished for threatening the male protagonism. This behavior is punished with defamation, harassment and symbolic aggressions. Moreover, the cases of online sexual violence identified in Spain clearly demonstrate the need to punish women and girls who wish to participate in the virtual world, connecting with people and experiencing affective relationships. On this, Valente et al. (2016) explain that "In addition to the physical and psychological harm caused by the threat, the danger of sexual assault operates as a reminder of male privilege, aiming to restrict women's behavior" (p. 14).

In this regard, female bodies are seen as susceptible to violence simply because they exist. Therefore, it is not uncommon for an aggressor to make several victims at once, considering that, due to cultural biases, the aggressor sees this phenomenon of victimization as something natural in relationships between men and women.

The phenomenon of gender-based violence can be even more serious on the Internet. Considering that the history of the virtual world is marked by a male predominance in the development and shaping of the network as we know it now (Poland, 2016), it is not surprising that Internet users perceive this space as part of male power. Associated with this, Sousa & Rodríguez (2023) point out that the characteristics of the Internet reinforce the feeling of anonymity and impunity, which can lead to an increase in aggressiveness, since perpetrators do not believe they will be held accountable for their actions.

Another case that shows the vulnerable situation of girls and young women is the one that occurred in Seville in 2012, in which a man committed grooming against more than 80 girls and young women, once again using blackmail and threats to hold them hostage to violence.

More recently, in 2023, it became known the aforementioned case of 20 girls, students of a high school in the city of Almendralejo, who were victims of pornographic deepfake. The case was reported before it was possible that the girls were victims of polyvictimization.

It is also worth mentioning the case of girls and women who were victims of boyfriends or ex-boyfriends. One case can be highlighted that drew particular attention: that of an ex-boyfriend, who harassed the victim on social networks, in addition to making numerous phone calls to her. The case, which occurred in 2022, revealed how online violence is mixed with offline violence, when he and a friend threw sulfuric acid in the young woman's face. It is certainly clear, as the European Institute for Gender Equality (2017) has argued, that there is no such thing as a divide between the so-called "real" world and the virtual one. What happens online is part of our social experience and is not confined to that space.

This case reveals how related online and offline abuse and aggression are. Violence permeates these worlds (Poland, 2016) and is perpetuated in a cycle that goes on and on and repeats itself.

Finally, as pointed out by Sousa & Rodríguez (2023), it is worth highlighting that, in fact, women with social prominence, such as artists, politicians and journalists, are also recurrent targets of cyberviolence. A journalist who was a victim of this type of violence gave the following statement: It is a systematic attack to take away the place you occupy and the mechanism to do so is to psychologically destabilize you (Carranco, 2023).

5.2. Agressors

As for the aggressors, there were 56 in total identified, as already anticipated by Poland (2016) and Sousa (2021), most of them (87%), are boys (41%), young men (20%) and men (25%). Another interesting fact is the lack of information about the aggressors. There is much more information about the victims, who end up being more exposed and, therefore, victimized again in the pages of the newspaper. This can happen because, clearly, what appears in the newspaper is usually the result of a complaint made by the victim and the corresponding relatives. In this sense, journalists have more access to information from this group. However, it is impossible not to reflect that, as a dominant group (Bourdieu, 1998; Saffioti, 2001), men are more protected, having their identity and personal data better safeguarded than women and girls.

All the reports used in this research that provide primary data on online violence, such as the studies conducted by the Spanish Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital (2022), the Instituto Avon (2021) and the Instituto Europeo de la Igualdad de Género (2022), confirm the fact that boys and men are the main perpetrators of cyberviolence, while women and girls are the main victims. The report "Gender-based digital violence: an invisible reality", carried out by the Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital (2022), points out that, in Spain, most of the aggressors are men and, often, acquaintances of the victims, being able to be partners, ex-partners, or individuals from the social or professional circle of the victims. In addition, in a significant number of cases, the perpetrators are young people, reflecting the high use of digital technologies by this age group.

On the other hand, the report Combating Cyberviolence Against Women and Girls by the Instituto Europeo de la Igualdad de Género (2022), highlights that aggressors frequently take advantage of anonymity and the feeling of impunity provided by digital technologies to commit acts of violence. Another interesting aspect lies in the motivation of aggressions against women and girls, which are linked to issues of control and power, and they are grounded in hatred and misogyny.

It is also noteworthy that there are fewer perpetrators than victims, taking into account that a single perpetrator can claim many victims at the same time. As mentioned before, this phenomenon occurs, especially, in case of grooming or other forms of pedophilia. Such was the case of the Cadiz attacker, who was 22 years old when he was arrested for the first time, in 2008:

The Spanish police then found in their computer equipment 17.952 files with videos and photographs arranged in folders with the name of each of their victims or under more generic headings such as "Norwegians". They included nearly 70 minors, 43 of whom were identified as Estonians. (Cañas & López-Fonseca, 2017)

This time, one of his victims, a young Estonian man, committed suicide after being blackmailed by the offender who threatened to reveal intimate contents if his requests were not met. However, due to regulatory loopholes on the subject, a month later the offender was released. In 2016 he reoffended again and in 2016 he was arrested again. However, once he was released again, he returned to harassing children and teenagers on the internet and, in 2017, he was arrested again. Jankowicz (2022) points out that governments continue to fail women and systematized misogyny due to the lack of public policies to address the problem of cyberviolence.

Finally, in terms of age group, the aggressors are young men, generally slightly older than their victims. Although there are children as aggressors, this number grew especially because of the case that took place in the city of Almendralejo, pornographic deepfake, which involved more than 20 teenagers as aggressors, in addition to other 20 young people as victims.

Poland (2016), Sousa (2021), Sousa & Rodríguez (2023) and Jankowicz (2022) clarify that aggressors, unlike the self-perception of reckless teenagers who do not know what they are doing, they are actually older than their victims. The consequence of this type of argument is, precisely, to minimize online violence against women and girls and, therefore, to avoid the formulation of public policies, as well as the due accountability of aggressors and platforms.

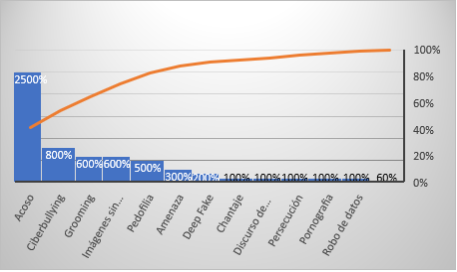

5.3. Types of Violence

Regarding the main types of cyberviolence that have been identified, the incidence of the following types stands out in the materials under analysis: harassment, cyberbullying, grooming, pedophilia, leaking of intimate images without consent, threats, blackmail, persecution, deepfake, hate speech and data theft.

Figure 6

Types of cyberbullying (absolute and relative values).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The most common types of cyberviolence were: harassment (41,7%), cyberbullying (13,3%), grooming (10%), leaking intimate images without consent (10%), pedophilia (8,3%) and threat (5%), pornographic deepfake (3,3%), and others (8,5%). As the main victims are girls and women, it is clear that the most common forms of violence are those that impose certain types of behavior, specifically sexual, and affect the honor and reputation of this group. As Foucault (1992) and Bourdieu (1998) consider, this violence directed at women comes from the dominant group, men, who wish to maintain their power and control over the dominated. Therefore, any behavior considered deviant is punished with humiliation, isolation and violence.

The online environment also replicates the hallmarks of patriarchy and male domination (Poland, 2016; Sousa, 2021) in that it is hostile towards women and, even those who behave in accordance with the demands of the dominant group, are at some point inevitably victimized. There are no ways to act appropriately when dealing with a dominated group, violence will always be used as an instrument of coercion and silencing.

Based on the results, it is possible to state that several practical measures can be taken to address cyberviolence in Spain. First, it is essential to implement educational programs that integrate digital and civic education into school curricula, addressing cyberviolence and promoting the responsible use of technology. Workshops and awareness campaigns should also be conducted in both schools and communities to inform about the consequences of cyberviolence and avenues for reporting and support.

In terms of legislation and public policy, existing laws need to be reviewed and strengthened to ensure that they adequately cover all forms of online violence and are effectively implemented. These laws should address gender, as its role in the dynamics of cyberviolence has been extensively demonstrated. For example, in discussion of the regulatory framework for artificial intelligence, the fact that it has a significant impact on the victimization of women and girls cannot be ignored. Cases such as the Almendralejo case show the serious problem of pornographic deepfakes. Therefore, thinking about the regulation of artificial intelligence also implies thinking about how to confront and mitigate the violence it can promote.

In addition, protection and support mechanisms for victims of cyberviolence, including hotlines and psychological and legal counseling services, must be established and improved. It is crucial to provide a safe and supportive environment so that victims can report abuse without fear of retaliation and receive the help they need to overcome the impact of the violence.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Based on the analysis of cases of online violence, it is emblematic that cyberviolence in Spain massively affects women and girls. They are the main victims and men are the main aggressors. Regarding the dynamics of cyberviolence in Spain, it is possible to highlight that female victims are generally very young and most of them are under 18 years old. When the victims are older women, they are usually women who were or are in a romantic relationship or are socially influential, as in the case of the singer Rosalía, who was the victim of a pornographic deepfake.

The aggressors are, in the vast majority of cases, men. The age of the aggressors can vary, but as a general rule they are young men. In some cases they are older than their victims. Finally, the main types of online violence are: harassment, cyberbullying, grooming, pedophilia and leaking of intimate images without consent.

The specific characteristics of the Internet mean that cyberviolence is characterized by a profound impunity. The aggressors rely on anonymity to victimize women and girls. This phenomenon means that the aggressors can make multiple victims at the same time and also that the same victim can be revictimized by different aggressors, who follow the flow of abuse and aggression, making this process almost infinite.

This scenario focuses on the problems of cyberviolence in Spain. It is necessary to admit that, although the legal framework, both in Spain and in Europe, has advanced to deal with this type of violence, it still faces countless problems imposed by the dynamics of this phenomenon.

Therefore, it is necessary to further discuss the regulation of social networks and the possibilities of counterattack in the field of public policy. It is essential to mainstream the gender perspective in the formulation of public actions and policies. It is also urgent to discuss the dimension of prevention, especially in the context of schools and universities, since both the main victims and the aggressors go to these spaces. In other words, it is crucial to invest in digital, emotional and media-based education. In this regard, it is essential to implement projects and modify the school program to include disciplines that address these contents and promote the prevention of their impacts.

Telecommunications platforms and companies have a duty to help civil society prevent and address this type of violence. It is unacceptable, for example, that artificial intelligence companies allow minors to produce pornographic material and furthermore that such materials do not receive an artificial intelligence tampering seal. Such a stamp can prevent such content from circulating freely as if it were real. That said, it is critical to identify that it is manipulation. If platforms and companies are unable or unwilling to execute these actions, it is essential for the Spanish State to intervene for the benefit of its population.

Such research is considered to shed light on understanding the phenomenon of cyberviolence in Spain. However, it is necessary to recognize the limitations of the empirical work supported by the cases published in the newspaper El País. Although the sample considers a long time span, from 2007 to 2023, it is important to note that it is a very particular sample of the reality, given that the cases of cyberviolence that become public are, generally, cases reported to the police. It is known that only a tiny fraction of violence cases are reported, and the same is true for cyberviolence. Therefore, it is essential that more studies be conducted to research this phenomenon and advance the debate on the dynamics of this violence.

Another way to deepen the study of cyberviolence in Spain would be to conduct surveys of victims, aggressors and witnesses. Educational spaces, such as schools and universities, account for many cases of cyberviolence, especially because their communities are made up of young people, who, as it has been observed, tend to spend more time online and also to act as social players in online violence.

These approaches would allow for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. It will contribute to the development of more effective strategies for preventing and addressing the phenomenon. In summary, although this study offers a valuable perspective on cyberviolence through the press, it is essential to complement this vision with research that includes other sources and methodologies.

7. REFERENCES

Ander-Egg, E. (1995). Técnicas de investigación social. Lumen.

Association for Progressive Communications. (11 de septiembre de 2023). Online gender-based violence: A submission from the Association for Progressive Communications to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. https://acortar.link/7JpNAg

Bardin, L. (2016). Análisis de contenido. São Paulo: Ediciones 70.

Bericat Alastuey, E. (1998). La integración de los métodos cuantitativo y cualitativo en la investigación social: Significado y medida. Ariel, S.A.

Bernardo, A. B., Tuero, E., Cervero, A., Dobarro, A., & Galve-González, C. (2020). Bullying and cyberbullying: Variables that influence university dropout. Comunicar, 64, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.3916/C64-2020-06

Bosch, N. V., & Gil-Juarez, A. (2021). Un acercamiento situado a las violencias machistas online y a las formas de contrarrestarlas. Revista Estudos Feministas, 29(3), e74588. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2021v29n374588

Bourdieu, P. (1989). O poder simbólico. Bertrand.

Bourdieu, P. (1998). La dominación masculina. Anagrama.

Cañas, J. A., & López-Fonseca, O. (17 de marzo de 2017). Ciberacosador, reincidente y sin castigo. El País. https://elpais.com/politica/2017/03/17/actualidad/1489742708_742554.html

Carranco, R. (23 de enero de 2023). La periodista Cristina Puig: Para atacar TV3 y el Faqs, lo hacían a través de su presentadora. El País. https://acortar.link/XemBnC

Castells, M. (1997). La era de la información, I. La sociedad red. Alianza. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3056851

Foucault, M. (1992). Microfísica del poder. La Piqueta.

González Río, M. J. (1997). Metodología de la investigación social. Técnicas de recolección de datos. Aguaclara.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2011). Cyberbullying: a review of the legal issues facing educators. Preventing School Failure, 55(2), 71-78. 10.1080/1045988X.2011.539433

Instituto Avon. (2021). Muito além do cyberbullying: a violência real do mundo virtual. https://institutoavon.org.br/pesquisa/

Instituto Europeo de la Igualdad de Género. (2017). La ciberviolencia contra mujeres y niñas. https://acortar.link/awaRy8

Instituto Europeo de la Igualdad de Género. (2022). Combating Cyber Violence against Women and Girls. https://acortar.link/5JIxve

Internet Watch Foundation. (2023). How AI is being abused to create child sexual abuse imagery. https://acortar.link/9uVerj

Jankowicz, N. (2022). How to be a woman online: surviving abuse and harassment, and how to fight back. Bloomsbury.

Ley Orgánica 10/2022. De garantía integral de la libertad sexual. 07 de septiembre de 2022. BOE No. 215. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2022/09/06/10

Limón, R. (18 de septiembre de 2023). De Rosalía al instituto: la inteligencia artificial generaliza la creación de imágenes pornográficas no consentidas. El País. https://acortar.link/WRZL2e

Lionço, T. (2019). Feminista, demoníaca, professora, psicóloga, inimiga pública. En R. S. Guimarães (Ed.). Gênero e Cultura: Perspectivas Formativas (Vol. 3.). Edições Hipótese.

Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital. (2022). Violencia digital de género: una realidad invisible. https://acortar.link/cRvEP9

Ministerio del Interior. (2022). Portal de Estadísticas Criminales. https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico/

Núñez Puente, S., Vázquez Cupeiro, S., & Fernández Romero, S. (2017). Ciberfeminismo contra la violencia de género: análisis del activismo online-offline y de la representación discursiva de la víctima. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 22(2), 861-877. https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.54240

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2015). Measuring cyberbullying: implications for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23(4), 1-7. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.013

Poland, B. (2016). Harassment, Abuse and Violence Online. Potomac Books.

Ronson, J. (2015). So you´ve been publicy shamed. Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Saffioti, H. I. (2001). Contribuições feministas para o estudo da violência de gênero. Cadernos Pagu, 16, 115-136. https://n9.cl/t6bhk

Sanjuán, C. (2019). Violencia Viral, análisis de la violencia contra la infancia y la adolescencia en el entorno digital. Save the Children España. https://acortar.link/0alTU3

Sensity IA. (2020). Automating image abuse. https://acortar.link/5ToYvc

Sousa, J. (2021). Violencia en Línea en Brasil: escenario y perspectivas. Razón y Palabra, 25(111), 174-187. https://doi.org/10.26807/rp.v25i111.1781

Sousa, J., & Rodríguez Ávila, N. (2023). El ciclo de la violencia en línea contra mujeres en Brasil. Chasqui: Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, 153, 117-131. https://doi.org/10.16921/chasqui.v1i153.4815

Sousa, J., Scheidweiler, G., Montenegro, L., & Geraldes, E. (2019). O ambiente regulatório brasileiro de enfrentamento à violência online de gênero. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias de la Comunicación, 16(30), 240-249. https://doi.org/10.55738/alaic.v16i30.530

Torres Albero, C. (2017). Sociedad de la información y brecha digital en España. Panorama Social, 25, 17-33. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6371386

United Nations. (2015). Combatting online violence against women & girls: a worldwide wake-up call. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/highlightdocumentenglish.pdf

Valente, M. G., Neris, N., Ruiz, J. P., & Bulgarelli, L. (2016). O Corpo é o Código: Estratégias Jurídicas de Enfrentamento ao Revenge Porn no Brasil. InternetLab.

Waldron, J. (2012). Approaching Hate Speech. En The Harm in Hate Speech (pp. 1-17). Harvard University Press.

Žižek, S. (2008). Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. Profile Books.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOLEDGMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Sousa, Janara; Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Methodology: Sousa, Janara. Validation: Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Formal analysis: Sousa, Janara; Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Sousa, Janara. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Visualization: Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Supervision: Sousa, Janara; Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Project management: Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar. Management. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Sousa, Janara; Rodríguez Ávila, Nuria and Rodríguez Martínez, Pilar.

Funding: This research work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation under grant PID2021-127113OB-I00.

AUTHORS:

Janara Sousa, PhD

University of Brasilia

Associate Professor in the Department of Organizational Communication at the University of Brasilia (UnB). She is part of the Graduate Program in Human Rights and Citizenship. She completed postdoctoral studies in Sociology at the University of Barcelona, Spain, and in Communication at the University of Minho, Portugal, focusing her research on online violence against women and girls. She holds a PhD in Sociology, a Master's degree in Communication and a Bachelor's degree in Journalism, all from UnB. She leads the Internet and Human Rights research group, coordinating projects such as the Brazilian Online Violence Observatory and the App School, which seek to understand and combat online violence against girls. She also coordinates the Online Violence in Educational Spaces project, collaborating with universities in Spain and Portugal.

Índice H: 8

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9056-5827

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com.br/citations?user=zAYtZqUAAAAJ&hl=pt-BR

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Janara-Sousa

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/JanaraSousa

Nuria Rodríguez Ávila, PhD

University of Barcelona

Professor of the Department of Sociology at the University of Barcelona. She is a member of the Applied Research and Knowledge for Society (ARKS) research group. She is a member of the Observatory of European Contemporary Social Welfare Systems and the UB Family Business Classroom. She runs the careers office for the Implementation of GIPE and GAEF. She coordinates the Social Economy Program of the University of Experience. She leads four projects of the ARACOOP line for the development and consolidation of training in Social Economy. She has been President of the School's Equality Committee since 2017 and she represents the UB in the EDI Group Equality, Diversity and Inclusion of the LERU 2018-2023. She has promoted the ODS Awards and coordinates the Employment Forum.

Índice H: 14

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9746-2495

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=n5O2tl8AAAAJ&hl=en

Scopus Author ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=20336599500

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nuria-Rodriguez-Avila-2

Academia.edu: https://ub.academia.edu/NuriaRodriguezAvila

Pilar Rodríguez Martínez, PhD

University of Almeria

Professor in the area of Sociology at the University of Almeria. She is responsible for the Comparative International Research group (HUM-1028). She is president of the CI35 Values Committee of the Spanish Federation of Sociology. She belongs to the TG10 Digital Sociology committee of the International Sociological Association and she is the coordinator of the group in the next congress of Rabat 2025. She leads a research project on the effects of hate speech in offline relationships of adolescents in Poniente Almeriense. She is the coordinator of the book "El análisis social del ciberespacio" (Social analysis of cyberspace), and her articles, "Hate-Speech Countering by Immigrant and Pro-Immigrant Associations in Almeria and "Gender effects of social media use among secondary schools' adolescents in Spain: extremist and pro-violence attitudes".

Índice H: 12

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6347-9117

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.de/citations?user=X_CLqeIAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pilar-Rodriguez-Martinez