Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI (2024).

ISSN: 1576-3420

|

Received: 02/08/2024 --- Accepted: 04/22/2024 --- Published: 30/05/2024 |

INFLUENCE OF TATTOOS AND THEIR DIFFERENT STYLES WHEN MAKING FIRST IMPRESSIONS

INFLUENCIA DE LOS TATUAJES Y SUS DIFERENTES ESTILOS EN LA FORMACIÓN DE PRIMERAS IMPRESIONES

![]() Enrique Carvajal Zaera: A. Nebrija University Spain. enriquecarvajalzaera@gmail.com

Enrique Carvajal Zaera: A. Nebrija University Spain. enriquecarvajalzaera@gmail.com

How to cite this article:

Carvajal Zaera, Enrique (2024). Influence of tattoos and their different styles when making first impressions [Influencia de los tatuajes y sus diferentes estilos en la formación de primeras impresiones]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1-28. http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2024.57.e866

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Tattoos have become ubiquitous today, with a prevalence of 38% in countries studied by Dalia Research. Their presence varies according to culture, country, gender, age, educational level, and geographical location, with unique aesthetics and meanings that motivate research on their influence on others. In the workplace, studies suggest that visible tattoos can negatively affect employment opportunities, leading to a deeper analysis of how different tattoo styles may influence the perception of service consumers. Methodology: The most popular tattoo styles were selected, including old school, new school, neo-traditional, tribal, blackwork, watercolor, Japanese, and realism styles. A quantitative analysis was conducted to examine the effect of colors and designs used in each style, contrasting traditional and modern elements. The aim was to understand how these elements influence the first impression of service consumers. Results: The results of the quantitative analysis revealed significant differences in the perception of service consumers according to tattoo style and elements. Patterns were identified in how different styles and designs affect the first impression, with some variations in preference depending on the type of service offered. Discussion and Conclusions: The findings suggest that the perception of tattoos when providing services is influenced by a combination of factors, including style, design, color, and service context. While some styles may be perceived more favorably than others, the acceptance of visible tattoos in the workplace appears to largely depend on the type of service provided. These results offer a specific insight into how customers perceive tattooed individuals providing services and can inform hiring practices and business policies.

Keywords: Customer; perception; satisfaction; service; body art.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Los tatuajes se han vuelto ubicuos en la sociedad actual, con una prevalencia del 38% en los países estudiados por Dalia Research. Su presencia varía según la cultura, país, género, edad, nivel educativo y ubicación geográfica, con estéticas y significados únicos que motivan la investigación sobre su influencia en terceros. En el ámbito laboral, estudios sugieren que los tatuajes visibles pueden afectar negativamente las oportunidades de empleo, lo que lleva a un análisis más profundo sobre cómo diferentes estilos de tatuajes pueden influir en la percepción del consumidor de servicios. Metodología: Se seleccionaron los estilos de tatuajes más populares, incluyendo vieja escuela, nueva escuela, neotradicional, tribal, obra negra, acuarela, japonés y realismo. Se realizó un análisis cuantitativo para examinar el efecto de los colores y diseños utilizados en cada estilo, contrastando elementos tradicionales y modernos. El objetivo fue comprender cómo estos elementos influyen en la primera impresión de los consumidores de servicios. Resultados: Los resultados del análisis cuantitativo revelaron diferencias significativas en la percepción de los consumidores de servicios según el estilo y los elementos de los tatuajes. Se identificaron patrones en la manera en que los diferentes estilos y diseños afectan la primera impresión, con algunas variaciones en la preferencia según el tipo de servicio ofrecido. Discusión y Conclusiones: Los hallazgos sugieren que la percepción de los tatuajes en el sector de servicios está influenciada por una combinación de factores, incluyendo el estilo, diseño, color y contexto del servicio. Si bien algunos estilos pueden ser percibidos más favorablemente que otros, la aceptación de los tatuajes visibles en el lugar de trabajo parece depender en gran medida del tipo de servicio prestado. Estos resultados ofrecen una visión concreta de cómo los clientes perciben a las personas tatuadas en el sector de servicios y pueden informar prácticas de contratación y políticas empresariales.

Palabras clave: Cliente; percepción; satisfacción; servicio; arte corporal.

1. INTRODUCTION

Currently, tattoos have a certain popularity in our society and this was demonstrated in the Dalia Research study, which revealed that 38% of the population in the countries studied have tattoos; noting that the prevalence of tattoos varies according to gender, age, educational level, geographic location and country.

Thus, the taste for tattoos and their styles is as diverse as the body art itself, where each style has its own aesthetics and meaning. In this context, research has been carried out on the influence of visible tattoos and their styles on second and third parties who see them.

There are several studies showing that, in the context of job search, the influence of visible tattoos have predominantly negative effects on employment opportunities. This study, by using quantitative methods, aims to go deeper into this aspect; analyzing whether all styles of tattoos influence the first impression on the service consumer in the same way and, depending on the style, assessing the degree of influence. For this purpose, the colors used and the designs, more traditional in contrast to the more modern ones, of each style have been taken into account.

The aim of the study is to give a more specific view by analyzing the first impressions of service customers who see tattoos of different styles on various parts of the body.

1.1. Current context of tattooing

Tattoos are highly popular in our society. A 2018 study conducted by tech start-up Dalia Research, involving more than 9,000 people from 18 different countries, showed that the percentage of tattooed people in the countries studied is 38%. However, the study also showed that the overall distribution of these percentages differs greatly between countries. For example, 48% of participants from Italy reported having one or more. In contrast, among individuals from Israel, this proportion was only 25% (Holmes, 2018).

With respect to age groups, 32% of 14-29 years of age were found to report having tattoos. The highest percentage of tattooed people, 45%, was in the 30 to 49 years age group. Out of the participants aged 50 years and older, 28% claimed to be tattooed (Holmes, 2018; 2020).

Regarding the distribution of percentages by gender, the study indicates that the proportion is 40% of women and only 36% of male respondents claimed to have one or more tattoos (Holmes, 2018; 2020).

Another data obtained from the study was related to the educational level of each individual. From this point of view and comparing the percentages, it was observed that 32% of people with a high educational level said they had tattoos, while in individuals who had a low educational level it was only 26% (Holmes, 2018; 2020).

Furthermore, it was concluded that 32% of the individuals studied who possessed tattoos belonged to the urban population while 26% was rural (Holmes, 2018; 2020).

As the studies conducted in 2018 and 2020 show, the prevalence of tattoos is as diverse as the body art itself. With the aim of finding out whether the acceptance of tattooing has evolved in parallel to the diffusion of these, the authors wanted to collect and analyze in this work various scientific studies, which have proven relevance, on this particular issue.

In this context, this research has been developed, taking into account the tattoos that are visible to third parties and the degree to which the style of tattoo influences the first impression on the consumer of services.

1.2. The theoretical framework

When referring to the term tattooing, the authors are talking about the insertion of colored particles under the skin with a needle. These color particles must be introduced at a certain depth in the epidermal tissue so that it can be permanently preserved, although nowadays the laser for tattoo removal influences the permanence of the tattoo (Bernstein, 2007).

According to Bernstein (2007), throughout history man has developed different techniques for the removal of tattoos that generated different and multiple damages in the individual. Currently, the use of surgical lasers has made it possible to minimize injuries and increase the efficacy of tattoo removal.

Thus, a tattoo represents and is considered as a permanent change in the body of an individual in the form of an image on the skin, which at most can be distorted or fade due to the influences of aging or skin regeneration (Bammann, 2008) and, thanks to current technologies, voluntarily (Aslam and Owen, 2013), disappear with surgical laser (Bernstein, 2007).

1.3. Tattoos in time

The tradition of tattoos dates back thousands of years, with the earliest samples of which there is evidence dating back to 3,000 BC. Since that first discovery, tattoos have been found throughout the history of almost all human societies. These facts are impossible to trace with the precision required for scientific research and from today's perspective (Bammann, 2008).

The oldest findings of body art can be dated to 3,000 years BC. The mummy found in the Alps in 1991 and referred to as Ötzi or the Iceman has numerous tattoos (Pesapane et al., 2014; Deter-Wolfa, et al., 2016; Brenes, 2021). Research suggests that the tattoos did not serve as body adornment, as they consist only of unadorned strokes and contain few ornamental elements. However, it is believed that the tattoos may have had a therapeutic purpose (Lobstädt, 2011). The reason for this assumption is the fact that several of the extant tattoos are found on Chinese acupuncture points (Dorfer et al., 1998).

There are also samples of the art of tattooing in ancient civilizations, with evidence of it being found in various parts of the world. In ancient Egypt, mummies have been found with tattoos. These tattoos were common on priestesses and were often associated with spiritual and ritual matters. Egyptian priestesses were responsible for many aspects of religious life and had connections to specific divinities. It is believed that tattoos played a role in magical rituals and religious acts, as well as serving for magical protection or fertility promotion (Brenes, 2021).

It should be noted that the perception and meaning of tattoos have varied throughout history and according to cultures. In the case of the Thracians, as documented in the writings of Herodotus, tattoos were used to distinguish nobility (Tassie, 2003; Brenes, 2021). This differential approach in the adoption of tattooing has also been observed in various cultures, being found in certain social groups as a symbolic manifestation of social status. However, in ancient Greece, the perception of tattooing changed and became associated with the idea of barbarism. The word “stigma” originated in that context to refer to marks on the skin, generally imposed as punishment on criminals and slaves. This change in perception reflects the construction of otherness and the association of tattooing with marginalization and subordination (Burrus, 2003; Brenes, 2021).

In ancient Rome, a contradiction in the perception of tattoos is observed. While slaves were marked as a form of control and demoralization, tattoos were also used to demarcate military ranks, strengthening bonds between soldiers and allowing easy identification of units (Marczak, 2007). These facts illustrate how tattoos can have multiple meanings depending on the cultural and social context in which they are found (Brenes, 2021). During the early Christian period in the Roman Empire, a time when Christians were persecuted and condemned by the Roman authorities, Christians needed forms of identification among themselves as a community. Thus, some Christians chose to tattoo symbols such as crosses or the fish symbol to recognize each other (Brenes, 2021). In this way, ancient Christians turned the symbols of submission associated with marks on the skin, used on criminals and slaves, into an inscription of divine election, an act of devotion and loyalty to their faith in adverse circumstances (Burrus, 2003).

However, with the legalization of Christianity under Constantine in the 4th century, and later, with the consolidation of the church, the attitude towards tattoos changed. The prohibition of the practice of tattooing was established by the ecclesiastical authorities, who saw in tattooing traces of paganism and considered that the ancient practices of marking on the skin could be associated with pagan rituals (Martí, 2012; Brenes, 2021). It is true that, despite the supposed prohibition of tattoos by the Christian church, evidence has been found in the Middle Ages that crusader knights tattooed motifs such as the cross. These tattoos may have served as a form of religious identification, ensuring that, should they die in battle, they would receive Christian burial.

In addition to the cross, it is plausible that some knights tattooed other motifs, such as dragons, which were iconic symbols of medieval chivalry. In particular, the dragon is also associated with St. George, the patron saint and protector of knights. Therefore, dragon tattoos could have been an expression of devotion to St. George and a symbol of chivalry and its ideals. This coexistence of prohibition and honor shows how the need to express identity and personal loyalty could have overcome the restrictions imposed by ecclesiastical authorities (Martí, 2012; Brenes, 2021).

As early as the 18th century, the English navigator James Cook first named the body drawings in one of his shipboard journals in 1774. The word he used was tattaw, which derives from the Polynesian word tatatau, meaning “to strike correctly”. Over time, the word tattaw evolved to be recognized today as tattoo, which translates from English to Spanish as tatuaje. As early as Cook's first trip in 1769, some of the fellow travelers were tattooed by Tahitians as a souvenir of the South Sea Islands. As a result, tattoos became a tradition, especially among seafarers (Lobstädt, 2011; Brenes, 2021).

In the course of the 19th century, however, the view in Europe changed and tattoos were considered uncivilized. Heavily tattooed people were ostracized and meant that many of them joined shows and circuses to present their bodies as an attraction in so-called freak shows. This was the only environment in which they gained acceptance, since in normal life they were seen as a threat, being punished with exclusion from society (Lobstädt, 2011; Brenes, 2021).

Another negative connotation of tattooing developed in the 20th century with the Third Reich. The National Socialist regime used tattoos as stigmatization. Concentration camp prisoners had their prisoner number tattooed on their forearm. In addition, the National Socialists also used tattoos to immortalize the blood group of each individual on Waffen-SS soldiers (Lobstädt, 2011).

In the post-war period, the biker and rocker movements were born in the United States. Within these groups, tattoos played a leading role. Members wore various symbols on their bodies to express affiliation with their respective group. These symbols were based on an internal “code”, according to which each motif was assigned an individual meaning. Eventually, this movement was transferred to Europe (Lobstädt, 2011).

However, the use of tattoos began to change again in the 1970s and following years, as the individualization of people came to the fore, leaving behind the concept of a group identity sign (Antoszewski et al., 2010; Lobstädt, 2011). Furthermore, in the course of the punk movement in the 1970s, the tattoo became a symbol of rebellion and protest (Rohr, 2010).

With the onset of the 2000s, it seems that tattoos have reached their zenith, appearing and being found in all strata of our society. In the mass media they appear as a marginal phenomenon and can even be seen as part of public advertising campaigns. Today, the mere fact that a person has a tattoo is no longer enough to attract attention (Lobstädt, 2011).

1.4. Different styles of tattoos

Lennon and Johnson (2019) conclude that tattooing is a different way of dressing the human body. Continuing with this concept as such, there are fashions, styles, colors, sizes, etc. which makes that among tattoos there is great variety.

Thus, they can be large or small, colored or black and gray. The style of a tattoo can even give the same subject a completely different look (Martina, 2018). Below, the authors will list and briefly explain some of the most relevant styles. And subsequently, these different styles will be used as the basis of our study.

1.4.1. Old School / Traditional

Figure 1. Old school tattoos.

Source: Adapted from Creative Tattoo Ideas, by Tatoo, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/635570566162681446/

The traditional tattoo style (Figure 1), also known as the old school tattoo style, traditional American tattooing, or classic tattooing, is characterized by bold lines and bright colors (Morrow, 2020). This style became popular in the early 20th century, along with the development of the electric tattoo machine. Typical motifs are eagles, pin-up girls, daggers or roses (Yang, 2019).

1.4.2. New School

Figure 2.

Tom and Jerry from the new school.

Source: Adapted from Tattoo-Spirit, n.d.(a) [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/705024516652495768/

This style of tattooing is inspired by Graffiti art, cartoons, hip hop and pop art (Figure 2). The roots can be found in the 1970s, when tattoo artists began to share their techniques and secrets. Due to the influence of customers, elements such as shading, depth, and 3D effects began to emerge (Yang, 2019).

1.4.3. Neo-Traditional

Figure 3.

Neo-Traditional eagle.

Source: Adapted from Tattoo-Spirit, n.d.(b) [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/6192518227771679/

Neotraditional tattoos (Figure 3) began to develop during the 1980s and 1990s (Yang, 2019). As the name suggests, this style takes strong inspiration from the traditional approach, but expands and evolves it significantly. For example, bold lines are mixed with finer lines to create a print or drawing with greater detail (Martina, 2018).

1.4.4. Tribal

Figure 4. Tribal tattoo.

Source: Adapted from Tattoodo, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/154740937191657897/

Tribal tattoos (Figure 4) are the oldest style of tattooing in the world. The roots of tribal tattoos can be found in indigenous body art in tribes all over the world, for example, from the Maori or the Polynesians. This is why the word “tribal” in this context is a general term. It includes several different tattoo styles that have their origin in the culture of different tribes and each of them is unique. However, almost all of them have one thing in common: they are always done in black with elaborate patterns (Morrow, 2020).

1.4.5. Blackwork

Figure 5. Blackwork tattoos.

Source: Adapted from Incompleta, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/36662184456447858/

Blackwork derives from tribal tradition, which explains why in this case, as the name suggests, only black paint is used (Figure 5). It is one of the most common styles among tattooed people (Yang, 2019). This can be justified by the fact that this style contains all types of tattoos through the extremely versatile use of black paint (Morrow, 2020).

1.4.6. Watercolor

Figure 6. Watercolor tattoos.

Source: Adapted from iNKPPL Tattoo Magazine, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/196047390019398191/

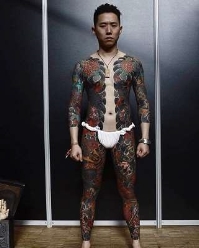

1.4.7. Japanese

Figure 7. Japanese tattoos.

Source: Adapted from TattoosBoyGirl, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/653866439655155670/

The traditional Japanese style is also known as Irezumi (Figure 7). It developed from criminal tattooing in Japan, which was banned in the 17th century. This style evolved with the mystique of criminality, the mafia and the danger associated with it. This is the reason why tattooing was banned in Japan for a long time. Within criminal groups, these tattoos were used as an initiation rite and a sign of commitment.

Most Japanese tattoos contain strong colors and curved lines. In this style, the part of the body to be decorated is completely tattooed without leaving the skin of the selected area visible. For this reason these tattoos are usually very time consuming and are considered extremely expensive. The classic motifs represent myths, samurai, monsters, dragons, but also flowers, koi fish or natural elements such as waves or clouds (Yang, 2019).

1.4.8. Realism

Figure 8. Realism tattoos.

Source: Adapted from Blog S.O.S Pedro, n.d. [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/19703317109932623/

Realism (Figure 8) arrived in the world of tattooing in the second half of the 20th century (Morrow, 2020). It was the product of the interaction of several factors. Access to better machines, techniques and skills became widespread and artists sought new ways to express their talent. This style hardly had any boundaries, with portraits and depictions of animals being the most popular motifs (Yang, 2019).

1.5. Studies on the perception of tattooed people

In order to analyze the perception that humans have about tattooed people, we have used as a starting point three studies, which will be detailed below and, which will allow a better understanding of the feeling about tattooed people and attitudes towards them.

1.5.1. Visible tattoos in the service sector: A new challenge for recruitment and selection

The first study that analyzed visible tattoos in the service sector and the effect it generated on third parties was conducted by Timming (2015). For the research, 25 in-depth interviews were conducted (n = 25), 15 with HR managers and 10 with visibly tattooed workers. All 25 interviewees were from Scotland and worked providing service.

The study analyzed the impact of prejudice against tattoos from the point of view of hiring people with tattoos (Allport, 1979; Devine, 1989; Bekhor et al., 1995; Degelman and Price, 2002; Dean, 2011; Timming, 2015).

As a result, Timming (2015) was able to demonstrate that visible tattoos in this domain have predominantly negative effects in the face of employment opportunities (Bekhor et al., 1995; Degelman and Price, 2002; Swanger, 2006; Dean, 2010; 2011) for tattooed people, years later confirmed by Moses (2020). However, there are some decisive factors that can influence perception (Allport, 1979; Devine, 1989; Brown, 2010) such as, for example, the part of the body on which a tattoo is placed, the type of company and the industry in which it operates. In addition, the proximity of the tattooed person to customers is also a key aspect, which some HR managers take into account in their decision (Bekhor et al., 1995; Degelman and Price, 2002; Swanger, 2006; Dean, 2010; 2011). However, they also look, to some extent, at the presumed expectations of consumers regarding the appearance of employed personnel. Finally, the nature of the tattoo itself, in terms of the style or motif used, may also influence the decision-making process (Timming, 2015; Moses, 2020; Ruiz, 2020; Woodford et al., 2022; Davies, 2023).

1.5.2. The effects of body art on consumer attitudes

The study presented below was conducted and published by Baumann et al. in 2016. The research conducted was about the effects generated on consumer attitudes towards people who cater to the public and possess visible tattoos (Baumann et al., 2016).

In the study, 262 people were interviewed (n = 262), out of which 50% were men and 50% women. In the implementation, the research team used photos of people who did not have tattoos but added body art with the help of Photoshop. The people photographed were four women and four men. The procedure was divided into two separate experiments (Baumann et al., 2016).

In the first experiment, participants had to imagine that they were in the hospital and had to undergo a routine operation. Each participant had to rate on a numerical scale from 1 to 7 (1 = 'not at all likely' and 7 = 'extremely likely') which of the depicted persons would be most likely to be the treating surgeon. All images were shown with and without tattoos (Baumann et al., 2016).

In experiment number two, the procedure of the first experiment was repeated. The difference, however, was that the subjects were asked to imagine a different scenario. In this case, they had to pretend that they had damage their car and that the person in the picture was the mechanic who was supposed to fix it (Baumann et al., 2016).

As a result of the two experiments, it could be concluded that all pictures showing a person with a tattoo were rated by the interviewees lower than those without a tattoo. In the case of surgeons, however, body art had a significantly more negative effect on the evaluation by the study participants. In the case of mechanics, on the other hand, the judgment of the participants was less negative (Baumann et al., 2016).

When providing services, specifically in education, Moses (2020) obtains similar conclusions about teachers being a barrier to their recruitment. According to Al-Twal and Abuhassan (2023), most decisions made in a selection process are based on intuition and subjective judgment (Bekhor, et al., 1995; Degelman and Price , 2002; Rynes et al., 2002; Swanger, 2006; Highhouse, 2008; Dean, 2010; 2011), with physical appearance (physical attractiveness, body weight, clothing, and intentional body modification, e.g., tattoos and piercings) being one of the elements that generates the greatest bias in the process (Allport, 1979; Devine, 1989; Brown, 2010; Timming, 2015). Although in most research related to selection processes, the effect of visible body art is negative, there are exceptions that show that in some very specific contexts it can have a favorable effect for the applicant (for example, in the selection of tattoo artists and nightclub staff) (Woodford et al., 2022).

In addition, female test subjects were found to be significantly more tolerant of tattooed people than their male counterparts. In summary, it can be said that study participants tended to rate tattoos negatively in general (Jeffreys, 2000; Baumann et al., 2016).

1.5.3. Negative attitudes toward tattooed people

The third study presented looked at general tattoo stigma and associated negative attitudes toward tattooed people. The research was published by Broussard and Harton in 2018.

In developing the study, the researchers collected license-free images of young men and women. The people depicted had large, conspicuous tattoos, but these were removed with Photoshop. Each study participant was shown images of a man with a tattoo, a man without a tattoo, a woman with a tattoo and a woman without a tattoo. In addition, the participants were shown six photos of similar people who had never had a tattoo, with the latter images serving as a distraction. The people in the photographs were then to be rated by the participants on 13 different characteristic traits, using a Likert scale for the rating. In addition to asking them about their demographics, alcohol consumption, and tattoo status and location (Broussard and Harton, 2018).

Broussard and Harton conducted two different experiments in their research. In the first experiment, 142 psychology students (n = 142) were interviewed. Overall, the evaluation of images of people with tattoos was very negative. In addition, it was also evident that female test participants showed a higher degree of tolerance than males. Participants who stated that they had tattoos also rated tattooed people more mildly than respondents who did not have tattoos (Brown, 2010). Beyond the data obtained, it was evident that women with tattoos were perceived as stronger in character and generally more independent (Jeffreys, 2000; Degelman and Price, 2002; Broussard and Harton, 2018).

The second experiment of the study involved 104 employees of Amazon Mechanical Turk. The experiment procedure was similar to the first experiment, with a few exceptions. However, it is worth mentioning that the average age of the participants in this case was significantly higher than in the first experiment. During the evaluation of this one, it could be determined that tattooed people were evaluated significantly more negatively than people without any skin ornaments. However, neither the age nor the location of the tattoo influenced the evaluation of the test participants. In conclusion, this experiment also revealed that tattooed people were rated as stronger and more independent. In this case, this assessment applied to both female and male genders (Broussard and Harton, 2018).

Years later Dillingh et al. (2020) published their study about the effect of tattoos on personal branding, suggesting that despite the prevalence of tattoos in modern culture, a stigma associated with them still persists (Degelman and Price, 2002). The results of research conducted with students confirm that tattooed people may be perceived differently compared to those without tattoos (Dean, 2010).

Similar to Broussard and Harton (2018), women with body designs were perceived as stronger and more independent, suggesting that some individuals associate tattoos with positive connotations (Jeffreys, 2000). However, despite these positive perceptions, images of tattooed individuals were rated more negatively on other character attributes compared to the same images without tattoos (Dillingh et al., 2020).

Dillingh et al. (2020) conclude that, although some positive stereotypes may be associated with tattoos, stigma still appears to exist, and tattooed people may be perceived more negatively than those without tattoos, based on the attributes assessed in the study. Not to mention that perceptions of tattoos may vary by culture, region and other sociodemographic factors. In addition, attitudes towards tattoos have evolved over time and will continue to evolve because cultures and social norms are dynamic.

2. OBJECTIVES

The first impression of a person is composed of several elements captured with the senses, although of all of them the evaluative one is the key. This influences the sympathy experienced towards someone met for the first time, generated in part by physical appearance (Hastie et al., 2014). This being one of the elements that generates the greatest bias in the valuation of people, it is necessary to know some of the aspects that compose it: physical attractiveness, body weight, clothing and intentional body modification, for example, tattoos and piercings (Timming, 2015; Al-Twal and Abuhassan, 2023).

Thus visual aspects are determinant for the evaluation and, therefore, for obtaining the first impression of a person, being the basis for the attribution of characteristics to the people when being met (Lennon and Miller, 1984). Consequently, tattoos, being a permanent modification of the body, affecting body appearance (Bammann, 2008), also come into play in influencing the first impression on someone (Woodford et al., 2022; Al-Twal and Abuhassan, 2023).

As explained in previous sections, people with tattoos are generally perceived somewhat more negatively. However, in his 2015 study, Timming found that there are several factors that influence the perception of tattooed people, which stem from the tattoo itself (section 1.5.1.). One of those mentioned is the style of the tattoo, an element on which the research was developed.

To approach the research, it is necessary to pose the following question: To what extent is the first impression of a person influenced by the style of the tattoo?

To answer this question the authors start from the following theory previously exposed: The style of tattoo used influences the first impression of the person wearing the tattoo.

To deepen in the subject matter, the following hypotheses are stated to put forward for verification or refutation this theory:

H1: Tattoo styles that feature dark colors create a more negative first impression.

H1.1: Tattoo styles that feature eye-catching colors create a less negative first impression.

H1.2: Tattoos that feature muted colors create a less negative first impression.

H2: Traditional tattoo styles create more negative first impressions than more modern styles.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to answer the research question and hypothesis, the study was conducted by using quantitative methodology, which required the use of questionnaires.

3.1. Selection of the research instrument

In order to analyze how the participants value the different variables and how they influence the first impression on third parties, even being a complex matter due to the existence of a great variety of subjective elements that can be affected by the different tattoo styles, different social research techniques can be used as appropriate for this purpose: natural observation of behavior, focused interviews, focus groups and the survey, being the social research techniques most commonly used to obtain this information. In this case, the so-called user satisfaction surveys will be used to be able to perform the measurement of the variables (Carvajal-Zaera, 2015).

Once the instrument for the research was selected, the questionnaire was developed based on scales validated in previous studies, the authors being Macintosh and Lockshin (1997), Wallace et al. (2004), Noble et al. (2006) and Molina et al. (2009). To adjust the questionnaire even more to the authors’ needs, the questions were submitted to a committee of experts for validation. In order to evaluate the responses and make them become quantitative data, the ordinal scale has been used, which allows for the matching of ten positions on the scale with numbers (from 1 to 10) (Padilla, 2007). The choice of an even-numbered scale avoids the tendency towards average scores, as could have been the case when using the Likert scale (from 1 to 5).

The instrument and medium used for data collection were online questionnaires, whose main advantage is the ease of distribution. With the help of the Internet, large amounts of data can be generated efficiently in a short time (Lefever and Mattíasdóttir, 2007). The SoSci Survey service program was used to conduct the online survey.

3.2. Structure of the online questionnaire

The online questionnaire was structured in two distinct blocks.

The first block was designed to capture the sociodemographic data of the participants, with questions on gender, age, education and employment status.

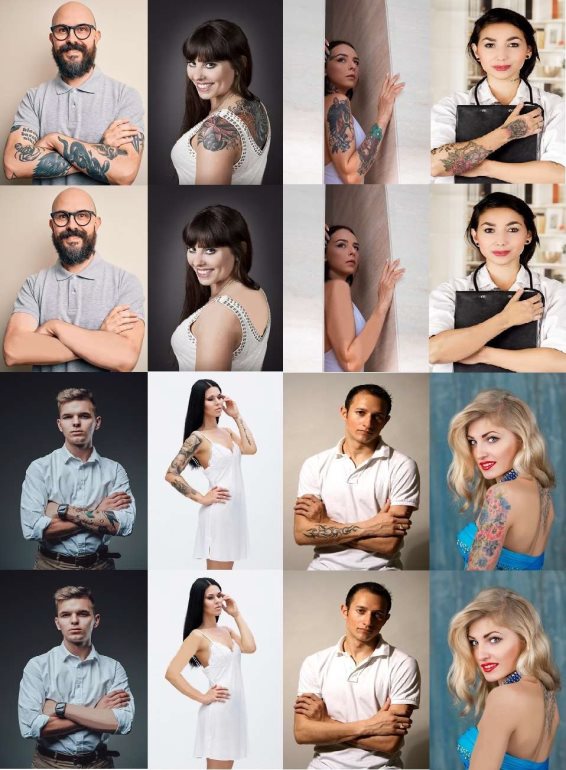

The second block focused on questions related to people's tattoos. For this purpose, 8 unlicensed images were obtained from the Shutterstock and Unsplash platforms (see annex) of tattooed people. Each of the images corresponded to each of the tattoo styles presented in section 1.4. Each participant was asked to rate their first impression upon viewing the images on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = negative; 10 = positive).

The same images had their tattoos removed with Photoshop (see annex). Survey participants were able to rate the tattooed images first and then the untattooed images. This was intended to provide a more accurate analysis of possible differences between individual tattoo styles, while avoiding focusing on the individuals in the images.

The images of individuals with and without tattoos were deliberately separated in order to avoid any influence of the order in which the images would be displayed. Already in the implementation of the study, participants were shown the images that included the tattoos first, as the research aims to capture the first impressions of the tattooed individuals and a true first impression is only given in the initial execution.

In relation to the images, in order to neutralize the influence of the images on the perception of the sample, attention should be paid to the selection of the model, the design and the technical quality of the photograph. In this study the authors have made a careful selection of free images published on the Internet with the intention of avoiding possible biases. Although the authors are aware that this choice, a consequence of the available resources, may influence the outcome of the study.

3.3. Implementation of the questionnaire

After the questionnaire had been reviewed by a committee of experts and before being sent out definitively, a pretest was carried out on a small sample to eliminate any lack of understanding or errors. Once the questionnaire was verified and approved, it was sent out and data were collected. The online survey was posted for a period of 4 weeks. In order to generate as many participants as possible in this period of time, the social networking platforms Facebook and WhatsApp were mainly used to disseminate the survey, mainly highlighting student groups for their great potential in interaction.

The disadvantage of using social networks as elements for disseminating the questionnaire should be considered, since users make their community participate in the information and, therefore, may generate bias in the sample, not only because of the user profile, in this case students, but also because of the values and culture they share with their community.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Description of the sample

To contextualize, the Spanish population has been selected as the universe, which according to the INE has 48,446,594 inhabitants (data 2023 Q4), 48.97% being men and 51.03% women. Following a distribution of the Spanish population according to age, it was found that 8.35% of the population is between 19 and 29 years old, 9.92% between 30 and 39 years old, 14.02% between 40 and 49 years old, 13.39% between 50 and 59 years old and 24.21% over 60 years old. In this universe, the sample to be interviewed should be n=384, with a confidence of 95% and a margin of error of 5%.

Although, as indicated in the theory, geographical and cultural diversity should be considered, since they affect the perception of the sample and help to generalize the results. In this study, being aware of the contribution of these elements to avoid biased conclusions and improve the general understanding of the tattoo phenomenon, it was not possible to include it due to the limited means for the implementation of the research and the collection of data from the different geographical areas of Spain.

For this study a total of 210 people participated through the online survey (n = 210). Of these 210 people, 69 were male (33%) and 141 were female (67%).

Regarding the age-related structure of the sample, 166 people (79%) belonged to the 18-29 age group, 36 people (17%) to the 30-39 age group, 4 people (2%) to the 40-49 age group and also 4 people (2%) to the 50-59 age group.

Regarding current employment, 141 persons (67%) declared to be students at present. The total amount of 65 people (31%) reported being employed and 4 people (2%) were unemployed.

On the other hand, with regard to educational level, 29 people (14%) reported having completed school, 11 people (5%) had completed vocational training, 126 people (60%) had a bachelor's degree or similar and 44 people (21%) had a master's or doctoral degree.

Thus, the sample obtained (n=210) was taken, considering the Spanish population as the universe, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 6.7%. Due to the nature of the sample, since it is not representative of the Spanish population (by age and sex) as a consequence of the means used to recruit participants, it should be declared as random. Therefore, all conclusions reached will refer exclusively to the sample.

4.2. Evaluation of first impressions

To evaluate first impressions, the researcher proceeded as follows: first, the first impressions of the 210 research participants were evaluated for each of the 16 images. The questionnaires were conducted by showing 8 images of different people (one image per style), a first time with tattoos and a second time without tattoos.

Each image was rated by the 210 participants on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = negative; 10 = positive), performing a simple average of all the participants' ratings (n = 210) for each image. Interestingly, all images shown with tattoos were rated more negatively overall by participants. These results are presented in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of first impressions.

|

Tattoo style |

With tattoo |

Without tattoo |

Difference |

|

Blackwork |

7.5 |

7.6 |

0.1 |

|

Japanese |

6.5 |

7.2 |

0.7 |

|

Neo-Traditional |

6.1 |

6.8 |

0.7 |

|

New School |

7.3 |

7.6 |

0.3 |

|

Old School |

6.3 |

6.7 |

0.4 |

|

Realism |

6.9 |

7.1 |

0.2 |

|

Tribal |

5.5 |

6.3 |

0.8 |

|

Watercolor |

6.3 |

6.7 |

0.4 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In order to minimize the influence of sympathy towards the subjects of the images on the interviewees and to pay more attention to the differences between the different styles of tattoos, the images with tattoos were shown first, followed by the images without tattoos In this way, the difference between the ratings of the two images allows us to determine the influence that each tattoo style has on the first impression. Thus, the greater the difference, the greater the influence of each style on the participant. Furthermore, these differences allow us to compare each style and its effect on perception.

At first glance, the differences in first impressions show that they are only slight for the tattoo styles Blackwork (0.1), New School (0.3), Old School (0.4), Realism (0.2) and Watercolor (0.4). On the other hand, the differences in first impressions are notably higher for Neo-Traditional (0.7), Japanese (0.7) and Tribal (0.8) styles.

Likewise, the simple mean of the differences (0.42) will be taken as the value that will allow us to discern and evaluate the level of influence of the tattoo on the participant. Styles with high influence are considered to be all those above 0.42, i.e. Japanese (0.7), Neo-Traditional (0.7) and Tribal (0.8). As styles with low influence the Blackwork (0.1), Realism (0.2) and New School (0.3) and, with medium value the styles of Old School (0.4) and Watercolor (0.4).

5. CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

5.1. Analysis and conclusions

To carry out the analysis on the influence of the different tattoo styles and based on the results obtained, it is necessary to answer the hypotheses and the research question, verifying or refuting each of them (section 1.6).

Hypothesis 1: Tattoo styles that feature dark colors create a more negative first impression.

With respect to this hypothesis, it was observed in the results that the two styles that contain large amounts of black color, such as Blackwork and Tribal, do not necessarily create a more negative first impression. The value of the difference is greater in the case of the Tribal style (0.8), while in the Blackwork almost irrelevant (0.1), suggesting that the negative influence of the tattoo is greater in the Tribal style than in the Blackwork with black being the predominant color in both cases. Hypothesis 1 is therefore rejected.

Hypothesis 1.1: Tattoo styles with bright colors create a less negative first impression.

Analyzing the data from the most colorful styles, such as Watercolor (0.4), Realistic (0.2) and New School (0.3) it was detected that the differences are lower and moderate. Thus, it is considered that vivid colors in tattoos as elements that generate a less negative first impression, therefore, this hypothesis is accepted.

Hypothesis 1.2: Tattoo styles that feature muted colors create a less negative first impression.

Japanese (0.7), Neo-Traditional (0.7), Realistic (0.2) and Old School (0.4) are considered as styles that use more muted colors. After observing the differences, it was determined that the results are not conclusive to accept this hypothesis, so it is rejected.

Hypothesis 2: More traditional tattoo styles create more negative first impressions than modern styles.

Tribal, Japanese, Old School, and Neo-Traditional are considered to be included among the styles considered traditional (Martina, 2018; Yang, 2019; Morrow, 2020). The ratings of the styles are disparate, while Tribal (0.8), Japanese (0.7) and Neo-Traditional (0.7) are high, for the Old School style (0.4) the difference is moderate or in the average. If the differences of the most modern styles are analyzed, Blackwork (0.1), New School (0.3), Realistic (0.2) and Watercolor (0.4), it can be detected that the differences and, therefore, their influence on the negative perception is lower and moderate in the Watercolor style. Thus, it can be concluded that traditional styles have a high and, in one style, moderate negative impact on the first impression, resulting in a more negative perception than in modern styles. Thus, this hypothesis is considered to be verified.

The theory presented in section 1.6 will be further tested.

Theory: the style of tattoo used influences the first impression of the person wearing the tattoo.

Based on the previously explained hypotheses, it can be assumed that the tattoo style affects the first impression of the participants. During the research, it was observed that the differences between the tattoo styles are in some cases high and in others lower, taking 0.42 (the simple mean) as a moderate value. In conclusion, tattoo styles influence people, taking into account that some have a greater influence than others, as can be seen in Table 1, ratifying this theory.

And finally, answering the question stated in section 1.6, to what extent is the first impression of a person influenced by the tattoo style (referring to the visible ones)?

As already mentioned, the influence of the tattoo is negative, but differences between tattoo styles are observed. Therefore, it must be said that the first impression of a person is influenced by the style of tattoo, this influence being higher in some styles than in others and may even be imperceptible.

The Net Promoter Score metric developed by the consulting firm Bain & Company makes it possible to assess the degree of customer satisfaction after receiving a service (Reichheld and Makey, 2011). Since the question posed was one with similar connotations to the questions posed by the Net Promoter Score (NPS), the authors wanted to find out what would happen if they applied the NPS metric to glimpse what direct perception the participants have of the people shown in the images with and without tattoos.

The NPS scale is rated from 1 to 10, with the interpretation of these evaluations being as follows: evaluations obtained between 1 and 6 show dissatisfaction, 7 and 8 show a neutral situation and, finally, 9 and 10 denote that the user is satisfied.

Thus, using the results obtained in Table 1, it can be said that, of the images with tattoos, all are below 7 except for the Blackwork and New School styles, which would indicate that except for these two styles mentioned, whose effect is neutral on the participant, the rest of the styles would generate dissatisfaction in the participant. Similarly with the images without tattoos, it was observed that those corresponding to the Blackwork, Japanese, New School and Realism styles have a neutral effect on the participants in the study, while the rest generate dissatisfaction. Thus, it is concluded that the effect of the people in the images is neutral or generates dissatisfaction and that the Blackwork and New School styles have a neutral effect on the participants.

Finally, the data related to the occupation and educational level of the participants, due to the inconsistency between the results obtained, prevents us from formulating solid conclusions relating these variables to the first impression caused by the different tattoo styles.

5.2. Discussion

It is important to bear in mind that the images, although they were selected with the aim of minimizing their effect, were obtained from free repositories, so the models and their tattoos, designs and photographic quality were quite different, which could have influenced the participants' assessment. Despite these differences, we have tried to minimize them to reduce as much as possible the influence they could generate. However, a neutral evaluation cannot be 100% guaranteed.

It is also important to keep in mind that each person has a different ideal of beauty and, therefore, the aesthetic perception is different and can influence the evaluation of the images. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize the first impression according to the style of the tattoo.

As for the images and the assessment of these by the participants, we could conclude that further minimizing the influence of the images and the people appearing in them, in order to focus the totality of the participants' attention on the tattoo styles, the authors are aware that, although possible, neutralizing the effect caused by the preferences and tastes of the participants is very difficult to avoid.

Regarding the sample, it is crucial to mitigate the bias derived from the initial distribution of the questionnaire among students and its subsequent dissemination through their communities in social networks. As has been evidenced, this practice leads to an unrepresentative sample and, moreover, generates bias by favoring the participation of individuals from the same cultural and geographic background. Unfortunately, in this study we have lacked the tools to counteract this bias, but it has provided us with sufficient knowledge to be able to resolve it in subsequent research.

As for the data obtained, since the sample is not representative of the Spanish population (by age and sex), despite the confidence level (95%) and the margin of error (6.7%), a consequence of the means used (Facebook and WhatsApp) to recruit participants, the sample is considered random. Therefore, the conclusions reached will refer exclusively to the sample. This result encourages us to obtain a greater number of interviews and to carry out the interviews using media more in line with the different age groups to allow us to approximate the sample to the profile of the Spanish population. In addition, it will provide sufficient data to obtain solid conclusions on the effect of tattoos in relation to the occupation and educational level of the participants.

In the research study it was observed that tattooed people were judged more negatively by the participants than non-tattooed people. From the data obtained, it can be seen that the different styles affect the first impression differently, with the more classic styles influencing the first impression to a greater extent than the more modern styles.

As for the influence of colors, it was concluded that both black and dull colors are not decisive in influencing the participant's perception. While bright colors generate a better impression than dark colors.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the tattoo research field has many interesting and varied aspects, due to the wealth of variables that can influence people's perception. For this reason, for future research the authors should adapt the data collection according to the age range, in order to try to obtain data representative of the Spanish population and avoid bias due to geographical and cultural factors. To guarantee, with the available resources, as much as possible the neutrality of personal preferences. And finally, to study in depth all the variables influencing perception, which will allow a complete overview of the subject.

Finally, there is a practical recommendation, both for employers and for people who have tattoos and work providing services. Since the first impressions caused by tattoos are mostly negative, especially when providing services the service sector, it is recommended to minimize their visibility by covering or removing them using laser technology.

6. REFERENCES

Allport, G.W. (1979). The Nature of Prejudice. Basic Books.

Antoszewski, B., Sitek, A., Fijałkowska, M., Kasielska, A. y Kruk-Jeromin, J. (2010). Tattooing and body piercing-what motivates you to do it? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(5), 471-479.

Aslam, A. y Owen, C.M. (2013). Fashions change but tattoos are forever: time to regret. British Journal of Dermatology, 169(6).

Bammann, K. (2008). Der Körper als Zeichen und Symbol. Tattoo, Piercing und body modification als Medium von Exklusion und Inklusion in der modernen Gesellschaft. En Exklusion in der Marktgesellschaft (pp.257-271).

Baumann, C., Timming, A. R. y Gollan, P. J. (2016). Taboo tattoos? A study of the gendered effects of body art on consumers' attitudes toward visibly tattooed front line staff. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 31-39.

Bekhor, P. S., Bekhor, L. y Gandrabur, M. (1995). Employer attitudes toward persons with visible tattoos. Australasian Journal of Dermatology, 36(2), 75-7.

Bernstein, E. F. (2007). Laser tattoo removal. In Seminars in plastic surgery. Thieme Medical Publishers, 03(21), 175-192.

BLACKDAY. (s.f.). Woman with tattoos wearing beautiful nightgown [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/67KDNa

Blog S.O.S Pedro. (s.f.). [Realism Tattoos]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/19703317109932623/

Brenes, T. M. (2021). Reflexiones sobre la historia, legitimación e inserción del tatuaje en el arte contemporáneo. Arte, cultura y sociedad: Revista de investigación a través de la práctica artística, 1(1).

Broussard, K. A. y Harton, H. C. (2018). Tattoo or taboo? Tattoo stigma and negative attitudes toward tattooed individuals. The Journal of social psychology, 158(5), 521-540.

Brown, R. (2010). Prejudice: Its Social Psychology (2nd Edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

Burrus, V. (2003). Macrina’s Tattoo. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 33(3),403-417. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-33-3-403

Carvajal-Zaera, E. (2015). La fidelidad del consumidor en la distribución detallista [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Davies, J. N. (2023). The Analysis of Personal Branding of People with Tattoos. JIM: Journal Ilmiah Mahasiswa Pendidikan Sejarah, 8(4), 3884-3892.

Dean, D. H. (2010). Consumer perceptions of visible tattoos on service personnel. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(3), 294-308. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521011041998

Dean, D. H. (2011). Young adult perception of visible tattoos on a white-collar service provider. Young Consumers, 12(3), 254-64.

Degelman, D. y Price, N. D. (2002). Tattoos and ratings of personal characteristics. Psychological Reports, 90(2), 507-14.

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5-18.

DCruz, S. (s.f.). Good Looking Young in Studio Man [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/PkDUiL

Del Rosario, J. (2020). Woman in black and red floral sleeveless top photo [Fotografía]. Unsplash. https://acortar.link/I95igW

Deter-Wolfa, Aaron, Benoît Robitailleb, Lars Krutakc y Sébastien Galliotd. (2016). The World’s Oldest Tattoos. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 5, 19-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007

Dillingh, R., Kooreman, P. y Potters, J. (2020). Tattoos, lifestyle, and the labor market. Labour, 34(2), 191-214.

Dorfer, L., Moser, M., Spindler, K., Bahr, F., Egarter-Vigl, E., y Dohr, G. (1998). 5200-year-old acupuncture in central Europe? Science, 5387(282). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5387.239f

Fotos593. (s.f.). Beautiful tattooed young doctor hugging a black binder in office background [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/yXP2Pm

FXQuadro. (s.f.). Tattooischer Kaukasier-Typ steht auf dunklem Hintergrund mit gekreuzten Armen. Fotografie eines jungen Mannes mit modischer Frisur. [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/Exjrsv

Hastie, R., Ostrom, T. M., Ebbesen, E. B., Wyer, R. S., Hamilton, D. L. y Carlston, D. E. (2014). Person Memory (PLE: Memory): The Cognitive Basis of Social Perception. Psychology Press.

Highhouse, S. (2008). Stubborn reliance on intuition and subjectivity in employee selection. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(3), 333-342.

Holmes, A. (2018). Who has the most tattoos? It’s not who you’d expect. Statista.

IKO-studio. (s.f.). Portrait of a beautiful young woman with a tattoo on the backs [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/RuKQVl

Incompleta. (s.f.). [Blackwork Tattoos]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/36662184456447858/

iNKPPL Tattoo Magazine. (s.f.). [Watercolour Tattoos]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/196047390019398191/

Jeffreys, S. (2000). ‘Body art’ and social status: cutting, tattooing, and piercing from a feminist perspective. Feminism and Psychology, 10(4), 409-29.

Krakenimages.com. (s.f.). Guter Glatzer mit Bart und Tätowierung mit lockerem Polo und Brille glückliches Gesicht lächeln mit gekreuzten Armen Blick auf die Kamera. Positive Person. [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://www.shutterstock.com/de/image-photo/handsome-bald

Lefever, S., Dal, M. y Matthíasdóttir, S. (2007). Online data collection in academic research: advantages and limitations. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(4), 574-582.

Lennon, S. J., y Johnson, K. K. (2019). Tattoos as a form of dress: A review (2000–18). Fashion, Style y Popular Culture, 6(2), 197-224.

Lennon, S. J. y Miller, F. G. (1984). Salience of Physical Appearance in Impression Formation. Home Economics Research Journal, 13(2), 95-104.

Lobstädt, T. (2011). Tätowierung, Narzissmus und Theatralität. Beltz Verlag. Wiesbaden.

Macintosh, G. y Lockshin, L. (1997). Retail relationship and store loyalty: AMulti-level perspective. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14, 487-497.

Marczak, A. (2007). Tattoo World [Honors Projects Overview]. Rhode Island College. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/29

Martí, J. (2012). La cultura del cuerpo. UOC.

Martina, T. (2018). Different Tattoo Styles. MrInkwells. https://www.mrinkwells.com/blogs/news/different-tattoo-styles-2

Molina, A., Martín, V. J., Santos, J. y Aranda, E. (2009). Consumer service and loyalty in Spanish grocery store retailing: an empirical study. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33, 477-485.

Morrow, J. (2020, March 31). A Beginner’s Guide: Popular Tattoo Styles Briefly Explained. Tattoodo. https://acortar.link/BZaBCK

Moses, L. V. (2020). Too tattooed to teach: A quantitative study of the relationship between tattoos and employment for educators in Central Texas [Doctoral dissertation]. Lamar University-Beaumont.

Noble, S. M., Griffith, D. A. y Adjei, M. T. (2006). Drivers of local merchant loyalty: Understanding the incluence of gender and shopping motives. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), 177-188.

Padilla, J. C. (2007). Escalas de medición. Paradigmas: Una Revista Disciplinar de Investigación, 2(2), 104-125.

Pesapane, F., Nazzaro, G., Gianotti, R. y Coggi, A. (2014). A Short History of Tattoo. JAMA Dermatology, 150(2), 145.

Rohr, E. (2010). Vom sakralen Ritual zum jugendkulturellen Design. Zur sozialen und psychischen Bedeutung von Piercings und Tattoos. En Körperhandeln und Körpererleben (pp.225-242).

Reichheld, F. y Makey, R. (2011) The ultimate question 2.0. Ingram Publisher Services.

Ruiz, S. (2020). Differences in Hiring Manager’s Ratings of Applicants Based on Visibility of Tattoos, Gender, and the Presence or Absence of an Equal Employer Opportunity Statement [Doctoral dissertation]. Alliant International University.

Rynes, S. L., Brown, K. G. y Colbert, A. E. (2002). Seven common misconceptions about human resource practices: Research findings versus practitioner beliefs. Academy of Management Perspectives, 16(3), 92-103.

Staykova, I. (s.f.). Junge schöne blonde Frau im blauen Kleid. Mädchen mit einer Tätowierung auf seiner Schulter, roter Lippenstift, dunkler Hintergrund [Fotografía]. Shutterstock. https://acortar.link/Kkxj0M

Swanger, N. (2006). Visible body modification (VBM): Evidence from human resource managers and recruiters and the effects on employment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25(1), 154-158.

Tassie, G. (2003). Identifying the practice of tattooing in ancient Egypt and Nubia. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 14.

Tattoodo. (s.f.). [Tribal Tattoo]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/154740937191657897/

TattoosBoyGirl. (s.f.). [Japanese Tattoos]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/653866439655155670/

Tattoo-Spirit. (s.f.)a [New School Tom y Jerry]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/705024516652495768/

Tattoo-Spirit. (s.f.)b [Neo Traditional Eagle]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.de/pin/6192518227771679/

Timming, A. R. (2015). Visible tattoos in the service sector: A new challenge to recruitment and selection. Work, Employment and Society, 29(1), 60-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014528402

Wallace, D. W., Giese, J. L. y Johnson, J. L. (2004). Customer retailer loyalty in the context of multiple channel strategies. Journal of Retailing, 80, 249-263.

Woodford, S. D., Wordsworth, R. y Malinen, S. (2022). Does my tattoo matter? Impact of tattoos in employee selection. NZJHRM, 1(22).

Yang, A. (2019). Ultimate Guide to Tattoo Styles: Popular styles explained with Images. Tattoos Wizard. https://tattooswizard.com/blog/tattoo-styles-%20explained

Note: The references (BLACKDAY, n.d.; FXQuadro, n.d.; IKO-studio, n.d.; Krakenimages.com, n.d.; Staykova, n.d.) correspond to links related to different image banks and currently do not direct to the images used in the work due to the content (images and texts) updating policy of the web.

AUTOR:

Enrique Carvajal Zaera

A. Nebrija University

Degree in CEYE from the University of Seville and PhD from the Complutense University of Madrid, MA in European Studies from the University of Seville, MBA from IE in Madrid and GSMP from the University of Chicago. Associate Professor at the Antonio de Nebrija University of Madrid, European University of Madrid and EUSA of Seville.

enriquecarvajalzaera@gmail.com

Índice H: 2

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5356-5847

ANNEX

Images used for the online questionnaire (BLACKDAY, n.d.; DCruz, n.d.; Del Rosario, 2020; Fotos593, n.d.; FXQuadro, n.d.; IKO-studio, n.d.; Krakenimages.com, n.d.; Staykova, n.d.).