Source: Made by the author based on the participant registration sheet for in-depth interviews.

doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.17-41

RESEARCH

BRAND MANAGEMENT AND CONSUMING TRIBE. A STUDY APPLIED TO THE SPANISH SURF BRANDS

BRAND MANAGEMENT Y TRIBU CONSUMIDORA. UN ESTUDIO APLICADO A LAS MARCAS DE SURF ESPAÑOLAS

BRAND MANAGEMENT E TRIBO CONSUMIDORA. UM ESTUDO APLICADO ÀS MARCAS DE SURF ESPANHOLAS

Paloma Sanz-Marcos1. Professor in the Department of Audiovisual Communication Advertising at the University of Seville. PhD in Communication and Bachelor of Advertising and Public Relations

1Sevilla University. Spain

ABSTRACT

This piece of research aims to deepen the notion of a consuming tribe from the perspective of tribal branding. The articulation of consumers through this type of grouping entails a series of implications with respect to the study of the brand that, directly, affects the classic brand management strategies. To this end, a potential specific consuming tribe, the Spanish surfers, as well as the marketing managers, has been taken as the object of study of those most representative surf brands that operate in the Spanish market in order to glimpse the scope of the brand conception that arises from the tribal concept, both in its reception and consumption dimensions and in relation to its possible model of management. The methodology has been based on conducting 11 in-depth interviews with the managers of the most representative surf brands operating in the Spanish market, and in holding 4 focus groups with a total of 29 participants from those Spanish areas where surfing has a greater presence. The results indicate that tribal marketing offers a radical version of the classic paradigms of the study of the brand evidenced, mainly, in a categorical problem manifested in a limited sophistication of the professionals that manage this industry in Spain.

KEY WORDS: brand management , strategy , brand, consumer tribe, tribal marketing, surf, sport

RESUMEN

Esta investigación se propone profundizar en la noción de tribu consumidora desde la óptica del branding tribal. La articulación de los consumidores a través de este tipo agrupación comporta una serie de implicaciones con respecto al estudio de la marca que, de manera directa, afecta a las estrategias clásicas de brand management. Para ello, se ha tomado como objeto de estudio a una potencial tribu consumidora específica, los surfistas españoles, así como a los responsables de marketing de aquellas marcas de surf más representativas que operan en el mercado español con objeto de vislumbrar el alcance de la concepción de la marca que surge a partir del concepto tribal, tanto en sus dimensiones de recepción y consumo como en lo relativo a su posible modelo de gestión. La metodología se ha basado en la realización de 11 entrevistas en profundidad a los gestores de las marcas de surf más representativas que operan en el mercado español, y en la celebración de 4 focus groups con un total de 29 participantes procedentes de aquellas zonas españolas donde la práctica del surf tiene mayor presencia. Los resultados indican que el marketing tribal ofrece una versión radical de los paradigmas clásicos del estudio de la marca evidenciado, principalmente, en un problema categorial manifestado en una escasa sofisticación de los profesionales que gestionan esta industria en España.

PALABRAS CLAVE: brand management, estrategia, marca, tribu consumidora, marketing tribal, surf, deporte

RESUME

Esta investigação se propõe a aprofundar na noção de tribo consumidora desde a ótica do branding tribal. A articulação dos consumidores através deste tipo de agrupação comporta uma série de implicações com respeito ao estudo da marca que, de maneira direita, afeta as estratégias clássicas do brand management. Para isso, tomaram como objetivo do estudo a uma potencial tribo consumidora especifica, os surfistas espanhóis assim como os responsáveis de marketing daquelas marcas de surf mais representativas que operam no mercado espanhol com objetivo de vislumbrar o alcance das dimensões de recepção e consumo como no relativo a seu possível modelo de gestão. A metodologia foi baseada na realização de 11 entrevistas em profundidade aos gestores das marcas de surf mais representativas que operam no mercado espanhol, e na celebração de 4 focus groups com um total de 29 participantes procedentes daquelas zonas espanholas onde a pratica do surf tem maior presença. Os resultados indicam que o marketing tribal oferece uma versão radical dos paradigmas clássicos do estudo da marca evidenciando, principalmente, em um problema de categoria manifestado em uma escassa sofisticação dos professionais que administram esta indústria na Espanha.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: brand management, estratégia, marca, tribo consumidora, marketing tribal, surf, esporte

Correspondence:

Paloma Sanz-Marcos. Sevilla University. Spain

palomasanz@us.es

Received: 22/02/2019

Accepted: 22/03/2019

Published: 15/03/2020

How to cite the article:

Sanz-Marcos, P. (2020). Brand management and consuming tribe. A study applied to the Spanish surf brands [Brand management y tribu consumidora. Un estudio aplicado a las marcas de surf españolas]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 51, 17-41. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.17-41

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/571

1. INTRODUCTION

The business community often focuses on how to use the social interactions of consumers to achieve optimal marketing results. New theories and tools are constantly emerging that allow companies to take advantage of consumer interactions to gain a competitive advantage. This piece of research focuses on the particular case of the organization of consumers around a community. Following Närvänen, Kartastenpää and Kuusela (2013), we are facing a new communicative prism in which the community has its most important role in understanding consumers. The power of communities in the market cannot be underestimated because the social bonds between subjects provide important value and resources that allow individuals to build their identity, as well as influence the consuming choices of others.

One of the recent developments in academic literature on such groupings in consumption is the introduction of tribal theory. In 1999 the academic Bernard Cova highlights an alternative approach to relational marketing, traditionally propelled by American thinkers, called tribal marketing that seeks to adapt to the demands of the Mediterranean market. This current is presented as a new perspective that allows us to understand the relationships between consumers (Tuominen, 2011).

Its main agent is the so-called consuming tribes, which recognize the importance of establishing emotional bonds between individuals over the consumption of the product itself (Silva and Santos, 2012). These consuming tribes have considerable implications for consumption and, more specifically, for the study of the brand. However, it is observed that academic literature seems to be scarce. Although there are works that study the behavior of the members of the consuming tribes in the online world (Jurisic and Azevedo, 2011; Pinto de Lima and Brito, 2013) or studies applied to environments such as fashion, music or cinema (Greenacre et al., 2013; Cova, Kozinets and Shankar, 2007), there are hardly any references linking brands and consuming tribes in particular. In this sense, one of its most significant features regarding the implications of the brand is the focus of tribal marketing strategies towards the creation of a network of people whose main objective is to find social interaction around brands (Saat, Maisurah and Hanim, 2015).

It should be noted that the traditional marketing perspective, which includes a dyadic exchange between the organization and the consumer, loses importance in this case. Instead, the tribal perspective advocates an approach between consumers by subordinating the role of the brand to the relationship between them. The brand supports the relationship between consumers and acts as a link between individuals (Dahl, 2014). This perspective focuses on the study of the consumer, understanding him as a truly active agent in consumption, thus highlighting his power in the strategic decisions of the brand. Thus, this current understands that value is created by the consumers themselves who are considered agents integrated in the marketing process with the capacity to contribute explicitly to the creation of values for brands (cf. Cova and Dalli).

In short, the consuming tribes offer important implications for the brand that, following Cova, Kozinets and Shankar (2007), do not imply a new form of organization, but a new way of thinking about the problems of the organization.

1.1. Conceptual differences between the consuming tribe and other related marketing terms

Following Canniford (2011b), despite having a research tradition that has more than twenty years of experience around the study of group consumption, there is a lack concerning the establishment of coherence between the theoretical and descriptive terms used to designate to consumer groups Likewise, authors such as Thomas, Price and Schau (2103) point out that, in the academic literature, many types of consumer communities proliferate, including consumer subcultures (Schouten and McAlexander, 1995), brand communities (Muñiz and O’Guinn, 2001) and consuming tribes (Cova and Cova 2002). However, while all these groupings focus on consumption, the distinctions between them are not entirely cleaThe concepts of consuming tribe and consumer subculture enclose a series of revealing differences ( Veloutsou and Moutinho, 2009; Canniford, 2011a) that emphasize the interaction between their individuals. Following Tuominen (2011), consuming tribes differ from consumer subcultures in that their connections between members are much closer. Schouten and McAlexander (1995) define the concept of consumer subculture as a distinctive subgroup of society that selects itself on the basis of a shared commitment to a particular class of product, name or activity of consumption, which has an identifiable and hierarchical social structure; a unique spirit, a series of shared values, unique jargons, certain rituals, and modes of symbolic expression. Through this definition, the researchers state that the concept contains an important sociological character that identifies a subgroup of society with a series of unique conditions that transfer them to consumption.

When it comes to understanding the concept of consumer subculture, it is necessary to recognize that, on the one hand, it is a term that drinks directly from sociology and stands as an alternative grouping to other social options, and that, on the other hand, considers a group of consumers who share a certain commitment to a brand. At the same time, another characteristic that helps us distinguish this concept from the consuming tribe is the subversive character that these consumer subcultures contain. Schouten and McAlexander (1995) point out that, as a result of their ethnographic study, there is a certain degree of marginalization and subversion among their members. The members of the community that they call HDSC (Harley-Davidson-oriented subculture of consumption) and that exemplifies this type of grouping, offer a series of behaviors that distinguish them from other forms of grouping in their interest to respond alternately to what has been established (Bazaki and Veloutsou, 2010).

Thus, among the members of the consumer subcultures there is a certain interest in marginality, in the rejection of what has been established and in the experimentation of the difference with respect to others. Indeed, this particularity is precisely one of the characteristics that more clearly present the differences between the consumer subcultures and the consuming tribes. This opinion is maintained by Goulding, Shankar and Canniford (2013), who argue that, unlike consumer subcultures, tribes are not subversions of dominant institutions.

With all this, it is paradoxical that the conceptual confusion regarding the consumer subculture affects other concepts. This fact is of special importance to us, given that the concept of brand community is commonly linked to that of the consuming tribe. For their part, De Burgh-Woodman and Brace-Govan (2007) try to explain the reason for this confusion, offering a point of view that understands that the concept of brand community comes from an evolution in the study of consumer subcultures when they affirm that, in recent years, the meaning of subculture in marketing discourse has been invaded by the concept of consumption, giving rise to the concept of consumer subculture, which in turn has led to the study of the brand community. In this sense, the term brand community, coined by Albert Muñiz and Thomas O’Guinn (2001), designates a group of specialized consumers that has no geographical boundaries, which is based on a structured series of social relationships between fans of a brand. Brand communities are characterized by a shared conscience, rituals and traditions, and a sense of moral responsibility. However, each of these qualities falls within a commercial and media sense of the masses and has its own particular expression.

Brand communities are participants in the larger social construction of the brand and play a vital role in its latest legacy (Muñiz and O’Guinn, 2001). In fact, the most relevant idea that emerges from the study of brand communities is the hegemony that the brand implies for its members.

Muñiz and O’Guinn (2001) argue that admiration for a particular brand is in fact the key to being recognized as a member of a given community. The devotion to a particular brand strongly supports the sense of belonging that members of that particular community can come to incorporate. In this sense, consuming tribes differ from brand communities precisely in this fundamental aspect that the brand acquires for the members: if, to these communities, the hegemony of the brand is its main badge, in the case of consuming tribes it is the relationships among its members those that are most important (Dahl, 2014). Goulding, Shankar and Canniford understand it the same way when they say that, unlike brand communities, consuming tribes do not look for iconic brands as the option to carry out their consumption experiences.

On the contrary, within consuming tribes, the social bonds established between consumers are more important than what is being consumed (Richardson, 2013). Somehow, the merely commercial occupies a second place in the life of these individuals who value loyalty to the community and its members over loyalty to the brand itself (Ruane and Wallace, 2015). In fact, the difference becomes noticeable between the members of the tribes and the communities themselves, which recognize that they have different perceptions and social impressions for society in general (Badrinarayanan and Sierra, 2018).

For their part, Cova and Cova (2002) argue that brand communities are explicitly commercial, while consuming tribes do not have such a characteristic. However, it should be noted that some academic currents recognize that, in the case of the online environment, these distinctive features seem to blur, considering a more permissive conceptual limit by which both groups of consumers can be considered equivalent (Pathak and Pathak-Shelat, 2015; Sierra, Badrinarayanan and Taute, 2016; Taute, Sierra, Carter and Maher, 2017).

1.2. Implications of consuming tribes for brand management

Throughout the academic literature, some theories have been developed about how consuming tribes should be managed resulting in a new approach around the implications they have for brand management. In this regard, the proposals of the aforementioned academic Robin Canniford stand out, who argues that the starting point to manage these consumers is to consider marketing and actions dedicated to them to be a massive cultural constellation that requires a limitless playing field from which consumers select, interpret and reject a profusion of cultural offerings (cf. Canniford, 2011b, p. 596).

Under this premise, Canniford proposes a management model to address consuming tribes that he calls a cultivation process that works as a mechanism by which marketing agents must support the markets, speeches and emotions of members of the tribes to facilitate their connection with the value of the brand (Canniford, 2011b). From this idea it follows that consuming tribes are, by default, content generating and fundamentally participatory of a common knowledge. That is why, in order to meet this need for community and exchange, facilitation by the platform marketing managers is required in which to improvise performances and gather the cultural sense of these tribes. In effect, this perspective shows the viability of a model that establishes that the strategies designed for the consuming tribes move away from those designed for other consumer groups, such as the aforementioned brand communities or consumer subcultures. This vision raises important implications for brand management with respect to consuming tribes.

Management of these consumers does not entail the explicit need to place the offer centralizing it in consumption as is the case with other concepts such as brand community. On the contrary, to approach these consumers, it is necessary to face opportunities that assign the product, service or brand to a useful point within the tribal network. This means that, just as consumers need core products and services in their lives, they also need cultural agents to help them maintain the actions of their tribal networks (Canniford, 2011b). In short, it could be said that consuming tribes obey a kind of uncertainty principle whereby the more these consumers are dominated by managers, the more likely it is that the tribe will do something to break the rules (Canniford, 2011b). That is why, in effect, consuming tribes respond to a new format of group consumption in which the brand occupies a second level for the benefit of the consumer himself.

Under this perspective, other authors such as Richardson state that the members of consuming tribes need to operate in conditions of relative freedom to create their own meanings around brands and activities. In this sense, they need freedom to question business narratives, leaving the role of the brand manager in the background (Richardson, 2013). From this idea, the tribal brand advocates the elevation of the consumer’s position as an agent creating brand meanings and values in which, ultimately, the marketing manager must facilitate independent development of consumers. Indeed, these tribes represent a new brand paradigm in which the consumer is central and whose domain is subject to its own members.

In order to explore consuming tribes under a brand perspective, it is necessary to consider under what available theories of brand management this type of consumer could be studied. Since tribal marketing theories recognize the consumer as a key piece in the process of creating the brand, cultural branding theories take center stage, which not only recognize the role of the consumer, at the same time, they consider their cultural context as creator of its value (Heding, Knudtzen and Bjerre, 2009). Proposed by brand expert Douglas B. Holt, cultural branding theory describes a process about how culture is used for brand management (Holt, 2004). This theory represents a framework for brand management that allows us to link the symbolic value of consumption to its social aspect, fundamentally, with consumers.

This management model assumes mainly that the meanings associated with the brand are collective and that culture is the basis for the creation of brand value. That is why the consumer adopts a capital role in brand management, because the meanings associated with products and brands come from the cultural context and their consumption becomes part of everyday social relationships. Thus, the theory of cultural branding is relevant to our object of study, because it raises cultural discourses and artifacts as part of the brand creation process (Canniford, 2011b). Under this model, the product is understood by consumers as a simple conduit through which they can experience the stories that the brand communicates (Holt, 2004a). Thus, the value of the product lies in its ability to provide consumers with a way to experience those stories. Indeed, brands become important cultural agents that, far from being understood as simple cultural mediators, become ideological referents that shape economic activity, rituals and social standards (Schroeder, 2009).

In short, the approach to cultural branding proposed by Holt (2005) is not only presented as an illustrative model of how brands operate in relation to culture, but, in turn, it constitutes an answer to the problem that brand management finds when it comes to understanding how brands create identity through cultural symbols.

1.3. The Spanish surfer consuming tribe

As we observe in the available literature about the consuming tribe and brands, in the specific case of its application to the surf industry, existing jobs are scarce. Standing out is the research by Dionísio, Leal and Moutinho (2008), which conduct a study of the tribal behavior of surfers in Portugal. However, there is a partial vision of the implications of the consuming tribes with respect to the brands since their theoretical precepts start from a certain disorder when it comes to confusing the concept of the consuming tribe with others previously commented as the brand community or consumer subculture. However, and although they do not include in their object of study the perspective of brand managers, they offer an interesting point for reflection on the implications that surfers have regarding branding.

The authors establish that Portuguese surfers must be considered a unique study phenomenon that requires a differentiated marketing strategy especially in brand management communications (Dionísio, Leal and Moutinho, 2008). Since our research focuses on the analysis of Spanish surf brands, we think it is necessary to know what characteristics Spanish surfers have as consumers. For this purpose, we have considered it necessary to provide a description that aims to justify the existence in Spain of what we consider to be a surfer consuming tribe.

Following Gonfaus, surfers make up what he calls a “Tribe of the Sea” (2006, p. 5). The author shows that, in effect, there is a feeling among surfers who exceeds the sporting nature of their practice. In his work a series of interviews are offered to some of the first surfers of the Basque coast, among which we highlight the opinions of one of the interviewees:

Although it sounds like a set phrase, surfing is a way of life, and as life itself, over the years it takes different perspectives […] Now, some people cross out sport surfing, seeing that every day it has more followers, especially among the youngest, and we always tend to the homologation of things. I, of course, am against this term so freely used that does so little justice to this type of expression (Iraola in Gonfaus, 2006, p. 85).

This feeling is equally recognized globally. Preston-Whyte (2002) states that surfing not only offers a lifestyle or physical activity, but also contains a series of experiences that provide the individual with vital meaning. In this regard, Stranger (2010), an academic with extensive experience in surfing studies, argues that among surfers there is a collective consciousness that manifests itself through the experience lived among surfers and that is reinforced through the moments of sociality that take place at sea. From these manifestations it follows that surfers share a common passion (Cova, 1997) towards the activity they practice.

Indeed, surfing is a transcendental activity in the lives of those who practice it that, despite manifesting itself as an individual experience, is often shared with other surfers. This is understood by Stranger (2010) when he argues that it is a culture of commitment in which, as Olive adds, relationships are created between people, places and communities, thus developing a global culture among those who practice it (cf. Olive, 2016, p. 171). Beaumont and Brown (2016), who study the behavior of surfers in the Cornwall area in southern England, show that on its beaches there is a common feeling that manifests itself in a shared awareness among surfers in the area They understand surfing as a way of life. This way, they ensure that a strong sense of connection arises around the location and the surfing community that makes them share a lifestyle beyond sport.

Something similar occurs in the Spanish case, Gonfaus argues that, despite the widespread conception among surfers that agglomerations complicate the activity, the relationship with others is valued closely when surfing; as one of the interviewees expresses: “You don’t have to enter the water only if there is no one” (Gonfaus, 2006, p. 58). From these statements it follows that surfers have a sense of attachment with a beach and with other practitioners. In short, the Spanish surfing tribe is characterized by a strong feeling of bonding that, on the one hand, is manifested around the common passion of a group for surfing and, on the other hand, it is accentuated with the manifestation of a feeling of union with those peers who belong to a specific locality creating a collective and protective awareness regarding a specific beach.

2. OBJECTIVES

The research problem posed in this work stems from the result of the theoretical review process carried out on the basis of the analysis of the previously mentioned studies and publications. Throughout this process, the existence of a series of unresolved issues has been identified which, by carrying out this piece of research, we intend to solve. Our proposal aims primarily to deepen the notion of a consuming tribe from the perspective of tribal branding. For this, we will take as a study object a specific consuming tribe, the Spanish surfers, as well as those responsible for marketing those surf brands most representative to the Spanish market.

This selection of the object of study is motivated by the idea of glimpsing the scope of the conception of the brand that arises from the tribal concept, both in its dimensions of reception and consumption (the consuming tribe) and in relation to its possible management model (brand managers). Specifically, the inclusion of brand managers in this study starts from the fact that, given the peculiar vision of the brand that involves tribal branding, it is interesting to consider the possible dimensions of brand management that the phenomenon of the Spanish surfer consuming tribe may have. As for the particular choice of the study of surfers as a consuming tribe, it is intended to contribute to the scarce literature found in this regard. It is a new and unexplored subject that, in the specific Spanish case, is nonexistent. Although, there are indications that, indeed, there is a certain community of Spanish surfers (Esparza, 2015; 2016) that are developed in a specialized market that has surf brands of Spanish origin, there are no works that study this specific phenomenon.

These absences are precisely those that our research intends to cover. Although, a priori, subjective perceptions are collected in the research carried out, by establishing the following objectives, we pursue:

1. To know the implications that consuming tribes constitute for brands in general, and for brand management in particular. This seeks to examine whether the existence of consuming tribes truly affects brands, their conceptualization and their management and, in that case, to describe what kind of consequences and relationships are established between brands and tribes.

2. To analyze the implications that consuming tribes have for surf brands specifically. Specifically, it is about making a delimited study of the consuming tribe of Spanish surfers and their possible implications regarding the brands related to the surfing sport they consume.

3. To determine if there is any kind of relationship between the management carried out by the representatives of the most representative surf brands for the Spanish market and the Spanish surfer consuming tribe. This objective is to analyze whether there is correspondence between the particularities expressed by the surfer consuming tribe, on the one hand, and the marketing actions proposed by surf brands, on the other hand. This is to examine whether the issuer (in this case, the manager of the surf brand) takes into consideration the receiver (in this case, the Spanish surfer consuming tribe), at the time of carrying out their various brand actions as well as their strategies

4. From the cultural implications of the consuming tribes, to determine whether cultural branding is an appropriate approach for their study. Since there is hardly any scientific rigor in classifying consuming tribes within the branding paradigms, it is intended to determine whether research on the cultural branding approach is a relevant approach to delimit the relationships between brands and consuming tribes.

Based on the scientific purposes proposed, we formulated the following hypotheses that the empirical analysis of this paper intends to verify:

H 1: Spanish surfers have a tribal consumption behavior.

H 2: The brand management perspective according to the tribal approach applied to the Spanish surfer consuming tribe implies that the brand occupies a secondary place.

The first hypothesis is formulated from the aforementioned previous work carried out by Moutinho, Dionísio, and Leal (2008) in which an analysis of Portuguese surfers is made. Parallel to this piece of research, our work conceives Spanish surfers as possible subjects who have a tribal behavior regarding surf brands.

With respect to the approach of brand management pursued by this work, the second hypothesis is based on the review of the bibliography we studied. The tribal marketing approach suggests that the brand does not occupy a primary place among its consumers, who value the linking value originated by it (Cova, 1997) with respect to its own consumption. In this sense, it is intended to establish what kind of implications this position of the brand would have regarding its management.

3. METHODOLOGY

For this study, it has become necessary to combine different qualitative research methods. Since our objectives include analyzing, on the one hand, the management of brands and, on the other hand, their reception by surfers, it is necessary to comply with a method that includes the achievement of these needs. In particular, in order to access the perspective of brand managers of the selected surf brands, we have used the in-depth interview technique (Kvale, 2011; Olaz, 2012). In the case of the reception of messages by surfers, the qualitative research technique known as focus group has been used (Rubin and Rubin, 1995; Walle, p. 2015).

For the design of the content of the interview, in the first place, and following the scientific logic, we have started from the hypotheses and objectives indicated above in order to elaborate the specific questions to be asked in the empirical sample. It should be noted that we have operationalized the questions based on academic literature taking into account theories of cultural branding and theories of the consuming tribe with respect to brand management. In this sense, the questions developed for the interview with the brand managers are the following:

1. How would you define the brand you work for?

2. Do you think it is important that your brand be distinguished as a brand that is designed exclusively for surfing?

3. When developing your brand strategies, do you differentiate between an expert or regular audience in the practice of surfing and a new or moderately initiated audience? Do you differentiate between more consumer categories?

4. Do you think the brand could survive if it only had the target audience that is non-expert or that simply feels attracted to the surf culture despite not practicing it?

5. Do you think the brand is important to surfers?

6. Do you think that your brand and product design strategies take into account the attractiveness of surfing to reach other consumers who do not surf but who are attracted to the surfer style?

7. Do you think surfers are part of a tribe or community?

8. Is there a product that reflects the common passion that surfers feel about this sport?

9. Do you think your brand enjoys great notoriety or popularity? If so, what values ??are associated with that brand awareness?

10. Do you think your brand fits the aspirations of surfers?

11. Currently, in our society, there are some tensions such as the fight for gender equity, the economic crisis, urban escape, etc. Do you take into account any social tension to design brand strategies? In other words, does the brand respond to any of these tensions?

12. There are brands that use mythical stories in their strategies and / or brand communications to reach the consumer. Does something similar happen in your strategies and/or brand communications?

Regarding the design of the focus groups, and also keeping in mind the questions proposed in the in-depth interview, the questions developed for the focus groups are the following:

1. Could you tell which Spanish surf brands currently exist? Which ones do you think are more important?

2. Is surfing a solitary sport? Do you need to practice surrounded by other people?

3. Is the use of certain brands essential for surfing? In other words, can you surf without consuming brands?

4. What importance do you give to the consumption of surf brands?

5. Do you think there is a style of dressing, surfing, or even a specific musical style that identifies a surfer?

6. Are you surfers faithful to the same brand?

7. Are there rituals that are usually followed during surfing?

8. If you go to an event related to surfing, is the event itself or the relationship established with others what is important to you?

9. Do you feel heard by brands? Do you market products that interest you?

10. Do surf brands help you create a purpose in your lives?

11. Do you think that surf brands determine your way of thinking about surfing?

As in the case of in-depth interviews, the selection of the questions chosen for the focus group aims to address the research objectives and hypotheses set out above.

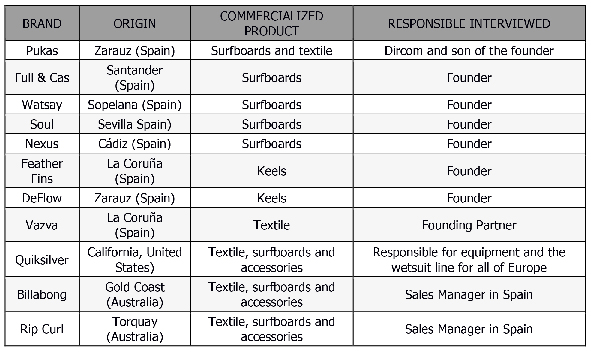

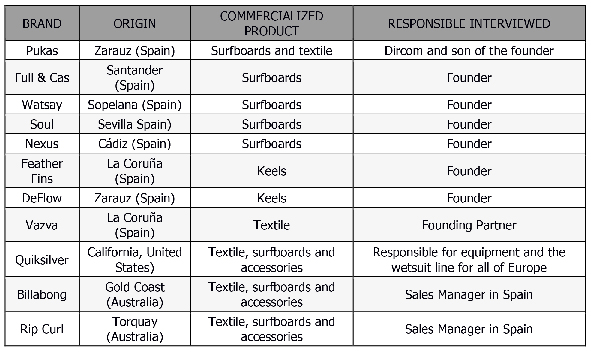

Regarding the selection of the chosen surf brands, several criteria have been considered: surf brands originated in the Iberian Peninsula, which have a consolidated commercial network and enjoy great visibility among Spanish surfers. In accordance with table 1, as a result, 11 persons responsible for the most representative surf brands operating in the Spanish market have participated, that is, Pukas, Full & Cas, Watsay, Soul, Nexo, Feather Fins, Deflow, Vazva, Quiksilver, Billabong and Rip Curl.

It should be noted that this sample shows the inclusion of three foreign surf brands, as is the case of the aforementioned Quiksilver, Billabong and Rip Curl. The decision to include them in the study responds to the objective of representing those brands with the greatest notoriety among Spanish surfers. Given that, despite not having originated in the Iberian Peninsula, they do operate in the Spanish market and are recognized as the three largest economically important firms in the world of surfing worldwide (Warren and Gibson, 2017), we have considered including them because they could greatly enrich our research.

Regarding the selection of Spanish brands, during the focus groups the participants were asked - through the first question of the interview - to recognize those most significant Spanish surf brands in order to identify their notoriety. These answers were also collated with the consultation of the commercial offer of Spanish online stores (1) specialized in surfing to identify their consolidation in the Spanish market. Likewise, this criterion has been supported by the virtual locator consultation of the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office under the name of “Gymnastics and sports articles not included in other classes for the practice of water sports. Plates and boards for surfing and snow, scooters and skateboards” (2) in their state as “asset”. The query made through this office has allowed us to verify the origin of the brands and their validity.

(1) The websites we consulted were: www.tablassurfshop.com, www.todosurf.com, www.surfmarket.org, www.mundo-surf.com, www.frussurf.com or www.surf3.es. This selection corresponds to the top ten of the search in Google of “purchase of surf equipment in Spain” carried out on February 20, 2018. The first ten positions of stores of Spanish origin have been considered, thus discarding the following ones of foreign origin: www.bluetomato.com, www.magicseaweed.com, www.wetsuitwarehouse.com and www.wetsuitoutlet.co.uk

(2) This denomination is the searching criteria most similar to the material for surfing available at this office to locate Spanish surf brands.

After the analysis of the selected brands, the following were discarded for the study: Slash, dedicated to the manufacture of surfboards of Asturian origin, has not been included in the study due to the impossibility of contacting any of its responsible persons; The Native Surfboards brands, of Malaga origin, and the Basque Peta Surfboards have not participated because, on the one hand, they enjoy a reduced local popularity (they were only identified in the Andalusian and Basque groups respectively) and, on the other hand, due to their dedication to the manufacture of artisanal surfboards, they have not been found available on the consulted websites. Finally, the Hotties brands, dedicated to the manufacture of wetsuits and CeCe Surfboards, dedicated to the manufacture of surfboards, have also been discarded because they are in decline and imminent closing process.

Table 1. List of respondents.

Source: Made by the author based on the participant registration sheet for in-depth interviews.

The duration of the interviews ranged from 15 minutes to one hour. The researcher traveled to the workplace of all those responsible for branding except for the case of two of the participants who, given the inability to contact them physically, were interviewed either by email or telephone. Prior to conducting the in-depth interviews, the interviewees signed a consent whereby the subjects were informed of the project and its confidentiality. In the case of telephone and email interviews, they were sent by email. For the preparation of the interview, the researcher followed a route questionnaire as it facilitates coherence between the interviewees and the interviewer (Krueger, 1998, p. 12).

Regarding the collection of testimonies and opinions of consumers, four focus groups were held with 29 participants from those Spanish areas where surfing has a greater presence, that is, the western-northern area of Spain in La Coruña (eight participants), the central-northern area of the Cantabrian in Asturias (six participants), the easternmost-northern area of the Cantabrian in the Basque Country (seven participants) and the southern zone with a group held in Andalusia (eight participants).

As for certain particularities of the subjects, it should be noted that there have been experienced surfers, 82.75% said they had been surfing for more than 10 years. Attempts have been made to represent women in all groups. However, and following the study by Mountinho, Dionísio and Leal published in 2008, it is complex to find women who surf. That is why, among the four focus groups, in the area of Galicia and Asturias there has been a single woman respectively, in the area of Cadiz two women, and in the particular case of the area of Basque Country we could not find any woman.

The duration of the interviews ranged from 40 to 96 minutes, the longest being the one held in Zarauz with a total of 96 minutes, and the shortest was the one carried out in Cadiz with a duration of 40 minutes. The meetings were held in places that allowed the dynamism and well-being of the participants, in the case of Galicia and Asturias, the meetings took place in the meeting room of a hotel and, as regards the Basque Country and Andalusia, the meetings were held in public centers that were closed to the public for that occasion. In all cases, water and food were provided as advised by Morgan (1998).

4. DISCUSSION

The results obtained from the in-depth interviews and the focus groups offer an interesting starting point to analyze the phenomenon of consuming tribes and their implications related to brand management applied to the reality of Spanish surfing consumers. In the present study, we have tried to verify if the concept of consuming tribe is valid for a specific segment: the group of Spanish surfing consumers, a term that, on the one hand, does not have too much tradition in academic literature and that, on the other hand, had not been applied to surfers in Spain. As it has been previously collected, the consuming tribe develops theoretically around a common passion, as the main feature that highlights the importance of the social links established between consumers against the object of consumption (Cova, 1997). This central axis of the consuming tribe implies that its members embrace an important sociological basis that determines that the relations established among them are the main reason of interest for participating in these tribes. The relationships among the members of the tribe, therefore, are what would define its essence.

From these principles, the first hypothesis of our work was configured, which affirmed that Spanish surfers have a tribal consumption behavior. This hypothesis was not corroborated after the qualitative empirical study carried out, since such emotional links were not found among surfers. The responses of the interviewees show that, although they share a common passion around the practice of surfing, no emotional link is established among their practitioners. In this sense, it is observed that, in the case of Spanish surfers, there is no need for vital belonging or affiliation. This is demonstrated by most of the responses obtained during the focus groups, among which we highlight the opinion of one of the Asturian subjects who recognized that to surf “[…] the [sic] the fewer people the better, if they are friends well [...] it can only be with my friends. They say that the ideal is three people”. Or that of a Basque participant professionally dedicated to surfing who assured that: “I prefer surfing the waves alone”.

This way, it is observed that the opportunity to establish emotional bonds, socialize at the time of sport or build a sense of group belonging are issues not valued, or nonexistent, among the participants, who express a preference towards practicing this sport alone. Therefore, there is no benefit of emotional connection that motivates Spanish surfers when it comes to belonging to what could be considered a possible surfer consuming tribe.

At the same time, this piece of research was intended to respond to the determination of the possible implications that Spanish surfer consumer tribes had for brand management. As we already mentioned, the consuming tribes have a complexity with respect to their management in which their strategies focused on the creation of a network of people whose main objective was to find social interaction around brands (Saat, Maisurah and Hanim, 2015). However, the results contradict these theories due to the already mentioned absence of common passion among surfers. The results show that, in effect, the tribal marketing theories formulated by Cova (1999) are not consistent with, nor applicable to, the reality of this particular market of Spanish surfers. A first reason to explain the results obtained can be sought in the applicability of this theory. Tribal marketing is questionable and too advanced in theoretical terms for the selected object of study, so that we were before an even utopian, overly evolutionary theory to the reality of the Spanish surfing market while, in this case, it is not a consumption system in which the established social bond is the main thing (Cova, 1995).

However, despite being a powerful market at an economic (Osorio, 2016) and cultural level (Esparza, 2011), the implications of the Spanish case regarding brand management are much less risky than we had anticipated. Our starting point considered analyzing those implications that were noted regarding the management of brand meanings because, as we saw in the theoretical basis of tribal marketing, this perspective advocated an approach among consumers subordinating the prominence of the brand to the relationship between them, and acting as a link between individuals. Ultimately, this configuration focused on the study of consumers, understanding them as truly active agents in consumption, and thus highlighting its power in the strategic decisions of the brand (Cova and Pace, 2006). Under tribal theories, we considered addressing the study of consuming tribes from a cultural branding perspective. However, the results we obtained show that tribal marketing offers a radical version of this approach. The truth is that this phenomenon would be inappropriate for study within the proposed branding schemes. This approach is explained through the results obtained in relation to several reasons.

First, participants in the focus groups tend to generally maintain that surf brands are understood as operating assets stripped of any type of intangible meaning. This is reflected in opinions such as those of one of the Galician participants who expressed that, when choosing a product, what prevailed was quality: “[…] I don’t buy a wetsuit for its brand […]”. In fact, this trend is also manifested among brand managers. The responses of these interviewees follow a trend focused on assessment judgments about the quality or performance of the brand against any symbolic value. This is the case of the head of the Full&Cas brand, who claimed that his brand was characteristic for its “good value for money”. It is observed that the target of this sector, in general, puts the basic benefits of the products over any immaterial attraction that could derive from the brand. This way, there is no complexity focused on social interaction around the brand, as well as regarding its management by brand managers as we will see below.

Second, although we started from the fact that the consuming tribes had a complexity around their management in which the culture was capital for their development and we assumed that this branding model would take into account those aspects related to the culture that would influence the management of the meanings that the members of the consuming tribes would take to provide the tribe with their own identity under the theory of cultural branding, it could be said that, given the responses obtained by the brand managers during the in-depth interviews, the conditions of the sector do not have enough sophistication to implement the strategic cultural mechanisms proposed by Holt (2004). This is evidenced by the results related to the fact that the responses of those responsible, in general, do not show any knowledge about these theories, nor do they claim to consciously apply the use of their own cultural branding strategy . A clear example is that of the head of the Pukas brand, who stated that “everything we communicate […] is less professional than it may seem, […] it is driven by impulses […]”, or those of the head of Feacther Fins when he expressed that: “No, in that sense no, we are very clear. Keels of high quality and a design we believe to be original or attractive centered in a recyclable packaging and a reasonable price, that is, in essence our brand, so it was born”. In the case of another of the brands, Nexo, its interviewee expresses that they do not carry out such strategies because, on the one hand, surfers “know all that they tell him and relativize it” indicating that he does not consider such formulas to be effective for this type of consumers and, on the other hand, that, in their opinion, they only care about “the wave and surfing”. In fact, participants in the focus groups generally acknowledge this idea when they express specific issues such as those expressed by one of the Cadiz participants: “the mainstream surfer is much more influential,” or one of the Galician surfers: “Here in the North that there is more culture and such, less, but in places where there is no culture more than before, you do let yourself be more influenced”, thus highlighting the messages addressed to issues that go beyond the quality or attributes of the product, they are not valued by experienced surfers.

For this purpose, we believe that the inadequacy of cultural branding for this market could respond to an intrinsic problem of the sector manifested in the training of these Spanish professionals. The answers obtained in the in-depth interviews lead us to suppose that the actors responsible for the brands in Spain have a series of training gaps that can be seen in their scarce mastery of brand management. Throughout the interviews, professionals usually do not distinguish between a strategic intellectual property asset such as the brand, and an asset absolutely anchored in the qualities, uses and advantages, such as the product. Explicitly, when asked about brand issues, they systematically respond based on product issues.

The above is related precisely to the second hypothesis of this work: the idea that a brand management perspective according to the tribal approach applied to the Spanish surfer consuming tribe implies that the brand occupies a secondary place. As in the first hypothesis, it is equally refuted after the empirical study. What a priori could lead to, in effect, the brand occupying a second place in the management of surf brand communication due to the importance acquired by the product, actually has to do with a question related to the scarce sophistication that characterizes this sector. The relationship between surf brands and the Spanish surfer consuming tribe, warns that, from the point of view of brand management, there is a communicational disconnection between the issuing pole, that is the brand managers, and the receiving pole, Spanish surfers. With regard to the knowledge of surfers, some of the interviewed professionals express that their brands consider it essential to promote the sense of belonging around surfing that consumers supposedly share. This is the case of the opinions of those responsible for the Quiksilver and Billabong brands, who point to a kind of tribal feeling that, as we said, is not recognized by surfers themselves.

These assessments highlight the disconnection between brand managers and Spanish surfers. Around these issues, it is necessary to remember the theoretical assumptions of Professor Canniford (2011a), who recommended that brand management practices dedicated to the branding of consuming tribes should be aimed at consumers in order to foster common passion among tribal members. Therefore, the theories of what Canniford called tribal branding was to recognize the freedom and power of consumers when creating the meanings of the brand. However, these practices are not recognized in the case of surfers and those responsible for Spanish brands. On the one hand, and according to what has been mentioned above, surfers do not have any evidence that expresses their consideration regarding the management of meanings, in fact, respondents value those benefits of products that point to the character of rational benefit, such as, for example, the quality of a wetsuit or the material of a surfboard.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Studying consumer behavior from a social point of view is a task that, together with the study of branding, is remarkably complex. Although the academic interest in understanding the way in which consumers relate to a brand is a notable trend today, it is appreciated that it is necessary to continue researching to provide demonstrable knowledge that describes the reality of the subjects. In the specific case of this piece of research, we have tried to explain the behavior of the consumer under a novel perspective that, although it does not reject the possibility that tribal marketing theories can be applied in certain specific contexts, and for certain types of consumers, does indicate that their generalization is not feasible.

This conclusion indicates that the tribal branding theory is configured as a scarcely defined theory that has a radical disharmony regarding the object of study of our research: the Spanish surfing market. In particular, there is a communicational disconnection that warns of the absence of relationships between brand professionals and their consumers. Instead, since the cultural perspective does not seem to respond to this market either, our research leads us to consider that the classic product brand management approach is configured as an adequate alternative to study brand management applied to this sector. Our contribution is that, on the one hand, the Spanish brand management professionals of the surf brands we studied do not recognize the application of such strategies, and, on the other hand, brand communications aimed at consumers do not offer evidence of such application. While it is true that the chosen interviewees are the main responsible persons for the brands analyzed in Spain, it is necessary to recognize that they are mostly surfers as well as brand managers. This fact could justify the reason for their legitimacy to perform the functions related to brand management in order not to cause the loss of authenticity to the detriment of their knowledge about brand management.

At the same time, it should be noted that the review of the academic literature carried out for this study allows us to deduce the following conclusion: the consuming tribe is a concept away from other concepts available in the marketing literature such as the consumer subculture and the brand community. The fundamental reasons that justify this conclusion are based on the fact that, on the one hand, unlike the consumer subculture, the consuming tribe does not present itself as a marginal or separate grouping of the dominant culture of a marked subversive nature and, on the other hand and with respect to the brand community, the members of the consuming tribes do not show an obvious loyalty to the brand. This perception questions the perspective of other studied authors who, paradoxically, find certain conceptual similarities between these terms, the above being therefore a possible reason that could respond to the refusal to consider Spanish surfers a consuming tribe.

However, these findings provide interesting conclusions for the study of Spanish surfers in general (that is, beyond the study of brands and branding strictly). Although this group of consumers does not show a tribal consumption behavior, it is proposed that future lines of research could apply the sociological theories of the urban tribe to study this reality from a more precise theoretical framework. This recommendation comes to respond to one of the limitations highlighted in this paper. The fact of analyzing the Spanish market is a restrictive condition that can limit the applicability of this study.

This condition in turn raises possible future research according to the applicability of these theories to other foreign markets, whether dedicated to surfing in order to establish comparatives or other natures and considering, where appropriate, other scenarios such as online media, where studies could be carried out to analyze the interactions in social networks among these consumers, taking into account their potential relationship with the brand. Also, another of the limitations that could open future lines of work is the consideration of the message communicated by the studied brands. The possibility of using other techniques such as, for example, the analysis of the discourse applied to the advertising campaigns of these brands could enrich research regarding those communication actions that reinforce the brand strategy.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR:

Paloma Sanz-Marcos: She is a professor in the Department of Audiovisual Advertising Advertising at the University of Seville. PhD in Communication (international mention by UC Berkeley, California) and a degree in Advertising and Public Relations, combines her teaching work with research in the area of communication. Member of the IDECO research group, he has presented communications in various academic meetings and has published articles and chapters of books on advertising and brand management. palomasanz@us.es

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6103-6993

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=NXgXVEEAAAAJ&hl=es