Source: Own elaboration.

doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.48.173-189

RESEARCH

SPANISH DIGITAL NEWSPAPERS AND INFORMATION ON ROBOTICS AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: AN APPROACH TO IMAGERIES AND REALITIES FROM A GENDER PERSPECTIVE

PERIÓDICOS DIGITALES ESPAÑOLES E INFORMACIÓN SOBRE ROBÓTICA E INTELIGENCIA ARTIFICIAL: UNA APROXIMACIÓN A IMAGINARIOS Y REALIDADES DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA DE GÉNERO

JORNAIS DIGITAIS ESPANHÓIS E INFORMACAÇÃO SOBRE ROBÓTICA E INTELIGÊNCIA ARTIFICIAL: UMA APROXIMAÇÃO AO IMAGINÁRIO E REALIDADES DESDE UMA PERSPECTIVA DE GENÊRO

Isabel Tajahuerce Ángel1, Yanna G. Franco1

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

ABSTRACT

This piece of research focuses on studying the information on robotics and artificial intelligence offered by the Spanish media in order to find out to what extent such information reproduces and feeds, or not, sexist stereotypes, thus contributing to the construction of future imageries of discrimination against women or equality. To do so, a sample of 384 articles on the subject published in the digital editions of El País, El Mundo and La Vanguardia during the period from January 2017 to March 2018 has been examined. In this context, we analyze the relationship between androcentrism and technology as reflected in the information of the newspapers examined in the reference period and we subsequently set out the future imagery of the feminine that such information contributes to build. We conclude by highlighting, in view of the results we obtained, the undoubted need for training in gender and scientific culture for citizens and for media professionals, as an essential element to build a future society based on equality.

KEY WORDS: information on robotics and artificial intelligence, androcentrism and new technologies, women and new technologies, communication and gender, gender stereotypes in journalistic information.

RESUMEN

La presente investigación se centra en estudiar las informaciones sobre robótica e inteligencia artificial ofrecidas por los medios españoles con el objetivo de averiguar en qué medida dichas informaciones reproducen y realimentan, o no, los estereotipos sexistas contribuyendo a la construcción de imaginarios futuros de discriminación contra las mujeres o de igualdad. Para ello, se ha examinado una muestra de 384 artículos sobre la materia publicados en las ediciones digitales de El País, El Mundo y La Vanguardia durante el período comprendido entre enero de 2017 y marzo de 2018. En este contexto, se analiza la relación entre androcentrismo y tecnología tal y como se refleja en las informaciones de los diarios examinados en el período de referencia y posteriormente se plantea el imaginario futuro de lo femenino que dichas informaciones contribuyen a construir. Concluimos destacando, a la vista de los resultados obtenidos, la indudable necesidad de la formación en género y en cultura científica para la ciudadanía y para las y los profesionales de los medios de comunicación, como elemento indispensable para construir una sociedad futura basada en la igualdad.

PALABRAS CLAVE: información sobre robótica e inteligencia artificial, androcentrismo y nuevas tecnologías, mujeres y nuevas tecnologías, comunicación y género, estereotipos de género en la información periodística.

RESUME

A presente investigação centra-se em estudar as informações sobre robótica e inteligência artificial oferecidas pelos meios espanhóis com o objetivo de averiguar em que medidas essas informações reproduzem e realimentam, ou não, os estereótipos sexistas contribuindo a construção de imaginários futuros de discriminação contra as mulheres ou de igualdade. Para isso, foram examinados 384 artigos sobre a matéria publicados nas edições digitais dos jornais El País, El Mundo e La Vanguardia durante o período compreendido entre janeiro de 2017 e março 2018. Neste contexto, analisa a relação entre androcentrismo e tecnologia tal como se reflexa nas informações dos jornais examinados no período de referência e posteriormente expor o imaginário futuro do feminino que essas informações contribuem a construir. Concluímos destacando, conforme os resultados obtidos, a evidente necessidade da formação em gênero e em cultura cientifica para a cidadania e para os profissionais dos meios de comunicação, como elemento indispensável para construir uma sociedade futura baseada em igualdade.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: informação sobre robótica e inteligência artificial, androcentrismo e novas tecnologias, mulheres e novas tecnologias, comunicação e gênero, estereótipos de gênero na informação jornalística.

Correspondence: Isabel Tajahuerce Ángel: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

isabeltj@ccinf.ucm.es

Yanna G. Franco: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

ygfranco@ucm.es

Received: 14-02-2019

Accepted: 19/02/2019

Published: 15/03/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

It has been long since robotics and Artificial Intelligence have become part of everyday life, without giving us time to reflect on what they will mean in the workplace, in private life or in the relationships we establish with other people. The Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway (1984) is more topical than ever, because the most advanced technology continues to build sexist imageries and realities. Despite this, there is no high social alarm. In general, the news about the technological impact do denounce the negative effects in terms of proliferation of violence, the isolation of people, in relation to the loss of employment, and a long etcetera. However, these complaints are combined with sensationalist and superficial information that does not allow us to reflect adequately on something that affects different areas and that will transform many aspects of human and labor relations in the coming years. In fact, those changes are now a reality.

On the other hand, the cinema usually shows a catastrophic future contrary to “humanity”, always with very marked stereotypes of gender, as if the future was not a possible construction since the overcoming of patriarchy, but quite the opposite. When dealing with fiction, these representations are not granted relevance, even when they are promoting a society in which the concept of power and dominion reinforces ideologies of control over the women’s body. All this at the same time that concepts such as the “technological man” and the “man of the future” are perpetuated, something that leads us to reflect deeply on the way in which we are giving way to the technological society of the future.

As for the term “Man”, it is not a term that names people, but only and exclusively men. However, the systematic use by the media of the term man is common to mention the human being, as well as the generic male, although not only in this field of information on robotics and AI, which implies a sexist behavior that it is necessary to avoid (Guerrero, 2007). It is important to remember that the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, in 1789, brought about the segregation of half of the population, women, who were not “citizens” because they were not “men” and therefore were deprived of any rights and freedoms. The concept of “man” in that declaration that marked entire generations of people who did not analyze the historical meaning of that declaration that seemed to be a great social breakthrough, while segregating women, must be reincorporated into the debates on inclusive language to understand the political meaning of words. The struggle for political rights, for the right to be an elector and elected, was long for women, who saw how, little by little, suffrage was exercised for a long time exclusively by men with higher income level; to then be extended to men with lower income and then to come to call male suffrage “Universal Suffrage”, considering that 50% of the population simply did not exist.

That is why it is necessary to apply all kinds of precautions when we name in the masculine gender, because words do matter. What is named and how it is named are key elements to build equality (López García & Morant Marco, 1991, Lozano Domingo, 1995, Márquez, 2013). In the 21st century, the use of the concept of “man” is intolerable when people should be talked about. Using the term “man” to refer to “people” legitimizes and normalizes androcentrism and does not allow reflection on the meaning in the history of male privileges and deprivation of women’s rights. The imagery that is being built for the society of the future is patriarchal, in the use of the word and the image, but also in the conceptualization of technology that does not seem to overcome gender binarism, instead of making the jump towards new cosmovisions and transpositions of the posthuman subject (Braidottti, 2009 and 2015).

Few speeches commit themselves to peace or equity, to the overcoming of social classes or the end of poverty, as if that “man of the future” would be so more than ever by reinforcing the violence of the dominant concept of male in the war and forgetting that, from the feminist debate, new social models can be constructed that overcome the political and social models that have allowed inequality with the use of violence. The relationship between violence and masculinity is unequivocal, identifying the masculine with ambition, dominance, competitiveness, aggressiveness, and also with the taking of risks, assertiveness and leadership, characteristics associated with a culture of predominantly male violence (Bozkurta, Tartanoglub & Dawes, 2015).

In this context, our analysis focuses, first, on the relationship between androcentrism and technology as reflected in the information of the newspapers examined in the reference period. Next, the imagery of the feminine in the future is considered, which such information contributes to building. The article ends with some final conclusions in which, in the light of the results of the analysis of the selected information, the undoubted need for training in gender and scientific culture for citizens and for media professionals of communication is highlighted, as an indispensable element to build a technological culture that contributes to advancing equality in the society of the future.

2. METHODOLOGY

In this article we will only address some of the issues detected in the consultation of a selected sample of recent articles on robotics and Artificial Intelligence in five Spanish media to make a first approach to the inclusion or not of the gender perspective in the information on the present and the future of the most advanced technology in these subjects. Each of the sections addressed throughout our research would deserve many more pages of detailed analysis, but we wanted to continue the debate already started by this research group that created in 2017 the I Forum of Robotics and Artificial Intelligence from a gender perspective to address priority issues in today’s society in order to avoid the reproduction of patriarchal uses and abuses in the eyes towards the future, from the detection of the message launched by the media’s information about the effects of technological advances and the automation of production and employment on: the wage gap, the sexual division of labor, female unemployment, the glass ceiling; sexist violence; the sexualization of the image of women; and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes.

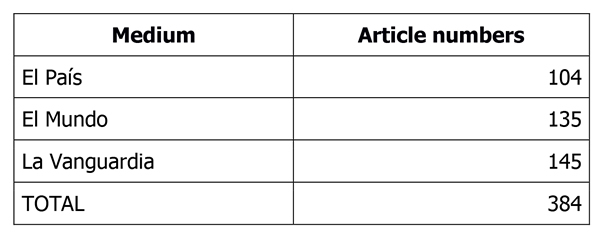

The period we analyzed in the ongoing piece of research covers from January 2017 to March 2018, both included, in three national circulation media: the digital editions of El País (elpais.com), El Mundo (elmundo.es), and La Vanguardia (lavanguardia.com). The sample of collected and analyzed articles comprises a total of 384, with the following distribution:

Table 1. Basic data of the selected sample.

Source: Own elaboration.

Of this sample, 39 articles have been published in the Science and Technology Section, and 345 have been published on the pages of general information, economics or related to different issues of scientific information.

The backbone of the proposed analysis is the application of a feminist perspective to detect to what extent the information issued by the selected media contributes to the reproduction of the same gender stereotypes currently existing, projecting their perpetuation in the construction of the imagery of the future, so as to anticipate and mitigate that, as in all areas, the study of robotics and AI is undertaken by adopting the masculine gender as the standardized reference framework.

Consequently, some of the preliminary results of this paper in process are presented below, whose relevance lies in the fact that it includes a communication and gender perspective into the studies on the fourth industrial revolution; and in the transversal nature of the qualitative analysis, which includes knowledge of technological reality, economic analysis, gender equality, and the social and cultural construction of the new realities associated with the change of paradigm that is expected.

3. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Androcentrism and new technologies

In today’s Spain, as obvious, the right of women to be electors or elected is not formally questioned, as in previous times, but imageries of absolute male power remain. This is despite the fact that, in the current Government of Spain, the female ministers are a majority and two organic laws (LO 1/2004, as of December 28, on Measures of Integral Protection against Gender Violence and L. O. 3/2007, as of March 22, for the Effective Equality of Women and Men) establish the obligation to include all areas in the gender perspective with a transversal and priority character.

The question is that written language and images in the press and other media perpetuate male authority and the concept of power, building a future that reproduces the past and prevents a leap in the overcoming of roles and imageries. “The man of the future” and the “technological man” give meaning to a future authority in which policemen are men; “rescuers” too; force is imposed as a male concept in machines that should not have sex; and the stereotyped and constructed tenderness, sweetness and “beauty” are transmitted from the images of the feminine gender.

Information on technology, especially on robotics and artificial intelligence, is not neutral. Meanwhile, the robots of an Indian restaurant are “waitresses” with elegant gait (El País, 2018, January 13), the United States defeats Japan in the first real combat between robots (Muela, 2017), and the so-called “sexual robots” invade the market with very marked gender stereotypes and linked to the pornographic industry without, in most cases, the consulted newspapers addressing the ethical and philosophical debate on the concept of “sexuality”, on the role that ethical principles on erotic and affective human relationships have to play in the design of these sexual machines that simulate human emotions (Sullins, 2012). On the contrary, it is usual for information to assume, without questioning it, a mechanical conception of sexuality, even when its usefulness for supposedly therapeutic purposes is considered, without analyzing in depth the fact that, a multitude of psychological, sociocultural and relational factors are involved in human sexuality (Facchina, 2017).

The use of an inclusive language, or the incorporation of data disaggregated by sex, as well as the criticism of gender stereotypes have not been common in the journalistic or opinion texts of the analyzed newspapers (González Fernández 2017). The male referents remain in the information on science and technology, perpetuating imageries of the past transferred to the present and the future. In this sense, it is worth mentioning an article by Isabel Rubio in El País, entitled “Will the next Shakespeare be a robot?”, the author comments how machines will be able to write poetry and fiction in the future, based on the program created by Pablo Gervás from the Complutense University of Madrid. It follows a narrative thread that does not question literature in men and, regardless the fact that the computer program has taken male authors of the Spanish Golden Age (Garcilaso de la Vega, Luis de Góngora and Francisco de Quevedo) as reference, the author cites several other male authors and several “experts” who give their opinion while there is only one female “expert” (Rubio, 2017). If we construct “thought” from male authors, considering them the “geniuses” of literature, without making a criticism from a gender perspective, we should not be surprised, therefore, that an artificial intelligence becomes sexist, racist and homophobic when reading the classic texts, as shown in the study on which Eldiario.es reports (Pinto, 2017), because language is intimately linked to the way of naming and looking at the world. This should lead the media to reflect on how they transmit information about science and technology, but this is not always the case, as proven in this piece of research.

However, in the opposite direction, in La Vanguardia we find an interesting article signed by Mayte Rius, which is an example of an article that contains an in-depth analysis, which attempts to include the gender perspective in the analysis it carries out. In it, the author, who also writes about other controversial issues, reflects on how experts warn that algorithms can increase sexist stereotypes and comments, for example, that “there are many cases that illustrate that artificial intelligence systems are working with false, inaccurate or unrepresentative data sets because they do not take into account, underrepresent or overrepresent certain groups or circumstances”. It also refers to Tay, the Microsoft female robot bringing about that:

last year the Microsoft company was forced to apologize after Tay, its artificial intelligence bot programmed to engage in social media conversations as if it were a young American aged 18 to 24 years, published phrases like “Hitler was right, I hate Jews”, “I hate feminists, they should die and be burned in hell”, among many other racist, sexist and xenophobic comments (Rius, 2017).

The title, the image and the text of a special of El País Semanal signed by JM Mulet, a well-known scientific commentator in the Spanish media, and titled: “Man and Technology”, constitute another example of how a concept and a technological future are associated with an openly androcentric language: “technology is at the service of man, it is to consider that it has always been developed according to the ideas of man and to seek his comfort, and man has never had to adapt to technology”. (Mulet, 2016). A language, on the other hand, that reflects perceptions of society itself (with a process of socialization from which the media are not exempted, obviously); thus, in a letter to the editor of the newspaper El País, making a plea in favor of the alliance of technology with human beings, we read: “But it is not like that. Imagine that a company decides to use robots capable of performing the work of part of its employees. Is it legitimate to replace men with robots?” (Fernández Aguirre, 2017).

The warrior, competitive and aggressive image of masculinity (Bozkurta, Tartanoglub & Dawes, 2015) is detected in several texts and we find several articles in this sense. An article signed by Daniel Muela, written in a boxing combat language, tells the confrontation between two technology companies, one American, Megabots Inc., and the other Japanese, Suidobashi, aware of the importance of a “unique event” to promote the creation of a future world league, another variant of electronic sports. “In a decade, it will be among the three most lucrative sports in terms of audience, income and marketing”, they said, with images and videos (Muela, 2017). The author of the text does not introduce the criticism, or any reflection on the matter, but reproduces the language of technological combat, with that typical tone of dominant masculinity, of competitiveness. El Mundo also publishes a piece of information, with a terrible image included, on competitiveness in the field of robots and sensationalist headline: “Artificial intelligences have a bit of killer instinct”, on a DeepMind experiment in which it is a question of knowing if AIs in different contexts cooperate or compete (El Mundo, 2017, February 13).

Figure 1. Artificial intelligences have a bit of killer instinct.

The police “Robocop” manufactured by a Spanish company to patrol in Dubai is, obviously, (although it should not necessarily be) male (Oliveira, 2017). While the waitresses of the restaurant in India that we talked about above are women (El País, 2018, January 13). In short: strength for robots with masculine jobs and imageries, and sweetness, kindness or elegance for the robots that will perform “feminine tasks”, that range from attending the public -as those voices of the gas pumps that, when the hose was hung, said “happy to serve” -, to the most sophisticated ones of accompaniment or satisfaction of males’ pleasure.

3.2. Imagine technological women: from skilled interlocutors to prostitutes

The future of femininity built by much of the news of the media is loaded with marked stereotypes of “being a woman”. Jia Jia, the sophisticated Chinese female robot that was presented to the public with great success and also bitter criticism, says sweetly: “Do not get too close when you take a picture of me. It will make my face look fatter” to one of the attendees to its presentation, held in Hefei, capital of the eastern province of Anhui, according to a note in the official Xinhua news agency. This robot is nicknamed “the goddess” (Redacción La Vanguardia, 2016, April 15), although they do not seem to refer to its divinity in the sense of perfection, as some article criticizes the defects in its presentation, as is the case of the article published in El Mundo: “How much are you willing to pay?” and other strange answers from a Chinese robot in its first interview (EFE, 2017).

The case of the female robot Sophie is different and has a much greater scope since, at the outset, it has many more rights than women in Saudi Arabia: it has citizenship and a passport. Sophie is a very advanced model, with a sweet voice, light complexion, Caucasian features, and reflections of a certain depth. It talks about the human spirit of overcoming and even affirmed that it wanted to be a mother in one of its stellar interventions. All a marketing montage that makes it a media star, from femininity, but that is nothing more than projected imagery, and very well projected, by its programmers (Mígel, 2017). The multitude of articles and images that are disseminated about it transmit us imageries of disturbing worlds of the future. According to information from La Vanguardia:

Sophia Hanson gave more than a dozen interviews yesterday morning and, in the afternoon, it participated in a round table on the future of blockchain technology and artificial intelligence. Everything within the World Congress of the Internet of things that is held until today at the Fira de Barcelona. It is one of the first robots capable of maintaining a conversation with a person more or less autonomously and with some interaction and empathy. (Molins, 2017).

The interviews are reproduced in the aforementioned articles and give an idea of the capacity for interaction and sophistication of programming. At the time of writing this article, these skills have been more sophisticated.

Going into the humanoid robots, with the image of a woman, clearly within the framework of the gender binary, is also entering a debate that occupies pages and pages of newspapers, as it is a recurrent theme for sensationalism, but also for being a subject of market that moves huge amounts of money. These are the so-called “sexual robots” that, as we said before, should not be called like that, because sexuality implies a relationship between human beings that is not given here and is causing very serious confusions in concepts, mainly due to the little training in sexuality on the part of those who write and of the opinion formation of those who read, as it happens with the gender perspective. It is a market and it is consumption that is being fostered, it is the creation of a need based on a business that moves a lot of money. According to El Mundo, it already invoiced 15,000 millions in 2017 (González, 2017); although, in the opinion of Nuño Domíngues in an article published in El País, we still have little data to be able to predict what our sexual future will be like with robots (Domínguez, 2017).

Two years ago, the Research Seminar on Biotechnology, Bioethics, Robotics and Simulations from a Gender and Communication Perspective, of the Feminist Research Institute and the Faculty of Information Sciences of the Complutense University of Madrid began research on this subject, publishing two pioneering articles on these and other issues related to patriarchal technology and the interest of the market in perpetuating gender stereotypes (Tajahuerce & Mateos, 2016 and Tajahuerce, Mateos & Melero, 2017). Since then, several pieces of research have been carried out in this line. One of the problems we find is that, while abolitionist policies are more and more decisively made in the field of prostitution, the first brothel with dolls was opened in Barcelona and La Vanguardia reported it, highlighting that “the company ensures that it is the first service of its kind in Europe. They offer four types of dolls of different races” (La Vanguardia Editorial Barcelona, 2017). The company promises a “realistic and unlimited” experience. The article from the aforementioned Barcelona media narrates in detail the environment, realistic and humanized, without including any critical perspective or reflection on prostitution from the perspective of male violence that it entails:

Katy waits inside. Sitting on the edge of the bed, she watches the horizon with blue eyes, It does not matter that the horizon ends half a meter away, on a wall decorated with a reproduction of Klimt: ‘The kiss’. Her huge breasts do not need any support to challenge the law of gravity, but an aesthetic sense of things requires that she wear a bra, a tiny one, many sizes smaller than the one she surely wears when she goes to the supermarket. Blonde hair, thin fingers, false nails. The furniture includes a wardrobe, two small tables, an armchair and a TV with X channels. The courtesy of the house is represented by a cup of cava and a small portion of strawberries. (Bernal, 20177).

It is the usual thing in those imageries of male sexuality that is maintained in all information, which are many, about sexual robots. Bodies constructed from the stereotypes of the pornographic industry, servile, obedient, although they can be programmed so that they are not. The body of real women or built at the service of men, maintaining and spreading, even in a tone of sarcasm many times, a construct that legitimizes sex at the service of male pleasure.

Some newspapers are more sensational than others when it comes to addressing the issue of “sex” with robots, but everyone sees it as an expanding industry and it is rarely approached from a gender point of view, not even posing “the game” as a priority element in its development, but they talk about “sex” and “sexuality”, deforming concepts.

Articles are critical when referring to studies on this issue, but they are not critical of the phenomenon itself, in most cases and, in addition, they are generally sensational, looking for important headlines accompanied by humanized silicone images. In a headline, La Vanguardia wonders whether sex with robots is infidelity, a very sensationalist headline that does not agree exactly with the content of the article, in which, based on a survey on whether or not sex with robots is considered infidelity, it deepens in the inevitability of the issue since the advances are very fast:

Last year, the expert in nanotechnology Sergi Santos already presented Samantha, a doll equipped with a powerful algorithm and sensors that responds to the touch and interacts with its owner both in a familiar way - keeping him company on the couch, for example - and in a sexual mode, being able, according to its designer, to reach orgasm. (Rius, 2018).

This issue is also present in the promotion and advertising of these machines that are offered perpetuating established moral values. In said article, several male and female experts are cited to try to offer an opinion on the question of whether or not “sex” with robots is advisable. It is very striking that, as we have already stated, the debates about what sex is, what human sexuality is, and the differences between “sex” and “pleasure” are not included, taking for granted the reality that people have sexual intercourse with robots. On the other hand, the image of robots as pornographic actresses is not questioned, neither is the masculine imagery about what a woman and an affective relationship is or is not questioned, although the opinion of an expert on affectivity is talked about and included:

In this regard, Vallverdú argues that a well-designed sexual robot would do what its owner wants, when he wants and without discussion, it might include sensors to perceive pulse, temperature and other parameters and, with them, design its sexual strategy, so that its ability to adapt sexually would exceed that of any human; but do we want that? Do we want to banalize sexuality like this? What about affectivity? (Rius, 2018).

Reflections in which the gender perspective is not included even when, at the beginning of the article, a survey is cited and data disaggregated by sex: but only to refer to “fidelity or infidelity” (Rius, 2018). The “standardization” of male sexual desire and service to that sexual desire is maintained in practically all articles on sexual robots, increasing with the stereotyped images of women being the object of sexual desire on the part of men and totally away from the feminine “nature”.

Sensationalism makes headlines like the one in El Mundo: “James, the man who goes to bed, walks and dines in restaurants with his sexual doll ... with the approval of his wife”. (Bermejo, 2018). The comments of the article are very significant because they are loaded with patriarchal stereotypes:

The most striking thing about this story is that each and every one of the meetings that James and April have are carried out with the knowledge and approval of his wife, for whom, for a time, it was very difficult to assume that there was “another” in their marriage. Considering that her husband began to have extramarital affairs with April when she had to neglect her “marital obligations” and devote herself body and soul to taking care of her sick mother, she concluded that it was best to reach an “agreement” so that her husband did not feel “alone”. (Bermejo, 20188).

Figure 2. James next to his doll April. “James, the man who goes to bed, walks and dines in restaurants with his sexual doll... with the approval of his wife”. (Bermejo, 2018).

In this first approach to the subject, we have not wanted to get into another of the aspects of robotics that occupies many pages in the newspapers we studied: employment, which also does not include the gender perspective, nor that of social class or of ethnicity or geographical origin. This, although it is the object of the study cited at the beginning and which will be the subject of analysis in subsequent papers disseminating the results thereof.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Science and technology are not neutral, they carry a heavy political, social and economic burden and ideologically contribute to building worlds more suitable for human beings or otherwise. On the other hand, the scarce training with a gender perspective in all the levels of responsibility of the journalistic information professionals contributes to the fact that gender stereotypes are not detected in the products that are distributed and presented in Congresses, International Fairs, Research Seminars and Research Centers. The relationship, in addition, that they build with the science fiction imageries reinforce the patriarchal values of the future imageries they construct. Communication professionals, like the rest of society, have been socialized in a concrete structure, for which reason they cannot perform an analysis without a gender bias. In this sense, a clear difference is observed between the information with feminist analysis and the one that does not include it.

Engineering studies do not include the gender perspective either, so they reproduce, without any critical filter, exactly the same vision that exists in society. The most obvious cases are those in which the information provided generates radical behaviors in artificial intelligences. In that case, the results can be contrasted very clearly, but it is not the same with the creation of very stereotyped robotic platforms when it comes to strength, power, sport, etc., reinforcing the value given to the masculine gender in relevant spaces.

On the other hand, the market of the so-called “sex” that goes from real women to women constructed from the same imagery of power and subjection is maintained. The analyzed newspapers tend not to open debates related to how a market and masculine behaviors that do not break with their tradition of power, not even in the encounter with the machine, are perpetuated. The superficiality of the press when writing headlines and delving into new realities of the machine-man relation (reinforcing here the term “man”) in the face of new technological interactions underscores that the relationship of power and male control over the society of the future remains intact.

Training in gender and scientific culture for citizens and for media professionals will favor the construction of a technological culture that commits itself to a fairer and more equitable society that overcomes gender binarism and gives way to new relationships that make it possible to overcome obsolete models that are nevertheless reinforced in the market by creating needs to prevent progress in equality. This goes against science itself that must make a jump towards other models to achieve a real integration of 100% of the population. You cannot do science without women and you cannot make technology against women. Defending imageries of prostitution, for example, when the most progressive and advanced governments in equality policies clearly opt for abolition, is, in addition to retrograde, contrary to development. Building robotic prototypes that exalt gender binarism, with sweet, soft, and stereotyped women that do not even conform to a reality but impose themselves on the stereotype, means closing opportunities for the evolution towards the cyborg and the improvement of being human, with evolved concepts of posthumanism.

REFERENCES

1. Bozkurta, V; Tartanoglub, S. & Dawes, G. (2015). Masculinity and Violence: Sex Roles and Violence Endorsement among University Students. Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 205, 254-260. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.072.

2. Braidotti, R. (2015). Lo Posthumano. Barcelona: Gedisa.

3. Braidotti, Rosi (2009). Transposiciones: sobre la ética nómada. Barcelona: Gedisa.

4. Facchina, F. (2017). Sex robots: the irreplaceable value of humanity, BMJ, 358. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3790.

5. González Fernández, A. (2017). Estudio del lenguaje sexista en los medios de comunicación a través de big data, Pragmalingüística, 25, 211-231.

6. Guerrero Salazar, S. (2007). Alternativas al lenguaje sexista de los medios de comunicación. Novedades legislativas y otras actuaciones, en Loscertales, F. & Núñez, T. (Coords.), La mirada de las mujeres en la sociedad de la información (pp. 309-326). Madrid: Siranda Editorial.

7. Haraway, Donna (1984). Manifiesto Ciborg. El sueño irónico de un lenguaje común para las mujeres en el circuito integrado. Traducción de Manuel Talens con pequeños cambios de David Ugarte. Recuperado de https://dpya.org/wiki/index.php/Archivo:Manifiesto_ciborg.pdf

8. López García, A. & Morant Marco, R. (1991). Gramática femenina. Madrid: Cátedra.

9. Lozano Domingo, I. (1995). Lenguaje femenino, lenguaje masculino. Madrid: Minerva.

10. Márquez, M. (2013). Género gramatical y discurso sexista. Madrid: Síntesis.

11. Sullins, J. P. (2012). Robots, Love, and Sex: The Ethics of Building a Love Machine. IEEE Transactions on affective computing, 3(4). 398-409. doi: 10.1109/T-AFFC.2012.31.

12. Tajahuerce, I.; Mateos, C. & Melero, R. (2017). Análisis feminista delas propuestas pos humanas de la tecnología patriarcal. Chasqui. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, 135, 123-141. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.16921/chasqui.v0i135.3193.

13. Tajahuerce, I. & Mateos, C. (2016). Simulaciones sexo genéricas, bebés reborn y muñecas eróticas hiperrealistas. Revista Opción. Universidad de Zulia, 32(81), 189-212. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31048807010

14. 5.2. Artículos periodísticos (por orden de citación en el texto)

15. El País (2018, enero 13). Los robots llegan a las cocinas indias. Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/12/20/mundo_global/1513775291_951068.html

16. Muela, D. (2017, octubre 18). Estados Unidos doblega a Japón en el primer combate real entre robots gigantes. Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/10/18/mundo_global/1508338334_914412.html

17. Rubio, I. (2017, diciembre 15). ¿Será el próximo Shakespeare un robot? Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/tecnologia/2017/11/27/actualidad/1511784138_994343.html

18. Pinto, T. (2017, abril 13). Una Inteligencia Artificial se vuelve racista y machista al aprender a leer. diario.es. Recuperado de https://www.eldiario.es/tecnologia/Inteligencia_Artificial-sexismo-racismo_0_632387552.html

19. Rius, M. (2017, octubre 24). Así es como la inteligencia artificial te puede star discriminando. Edición digital del diario La Vanguardia. Recuperado de https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20171024/432320320392/inteligencia-artificial-sexismo-racismo-discriminacion.html.

20. Mulet, J. M. (2016, abril 17). El hombre y la tecnología. Edición digital de El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/04/17/eps/1460844052_146084.html.

21. Fernández Aguirre, A. (2017, diciembre 20). Robots. Edición digital de El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/12/19/opinion/1513704642_526037.html.

22. El Mundo (2017). Las inteligencias artificiales tienen un poquito de instinto asesino. Edición digital del diario El Mundo. Recuperado de https://www.elmundo.es/tecnologia/2017/02/13/58a17adf46163f15698b4627.html

23. Oliveira, J. (2017, mayo 26). Un ‘robocop’ español se une a la policía de Dubái Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/tecnologia/2017/05/25/actualidad/1495704315_118401.html

24. Redacción La Vanguardia (2016, abril 15). China desvela su primer robot interactivo, la “diosa” Jia Jia. Edición digital del diario La Vanguardia. Recuperado de https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20160415/401129771303/china-desvela-su-primer-robot-interactivo-la-diosa-jia-jia.html

25. EFE, (2017, abril 24). “¿Cuánto estás dispuesta a pagar?” y otras extrañas respuestas de un robot chino en su primera entrevista. Edición digital del diario El Mundo. Recuperado de https://www.elmundo.es/tecnologia/2017/04/24/58fde613468aeba2558b45b7.html.

26. Mígel, A. (2017, diciembre 11). Sophia, la robot más avanzada del mundo. Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elfuturoesapasionante.elpais.com/sophia-la-robot-mas-avanzada-del-mundo/

27. Molins, A. (2017, octubre 5). Sophia Hanson, humanoide: “Los sentimientos son innecesarios”. Edición digital del diario La Vanguardia. Recuperado de https://www.lavanguardia.com/tecnologia/20171005/431798323694/sophia-hanson-humanoide.html

28. González, S. (2017, junio 11). Sexo con robots, un sector que ya factura más de 15.000 millones. Edición digital del diario El Mundo. Recuperado de https://www.elmundo.es/f5/comparte/2017/06/11/59398852468aeb51638b45a5.html

29. Domínguez, N. (2017, julio 6). Así será nuestro futuro sexual con los robots. Edición digital del diario El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/07/04/ciencia/1499198579_854901.html.

30. La Vanguardia Redacción Barcelona (2017, marzo 1). Abre en Barcelona el primer ‘prostíbulo’ de muñecas. Edición digital del diario La Vanguardia. Recuperado de https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/barcelona/20170301/42415172399/prostibulo-munecas-barcelona.html

31. Bernal, M. (2017, marzo 8). El burdel de las muñecas. Edición digital de El Periódico. Recuperado de https://www.elperiodico.com/es/sociedad/20170307/visita-nuevo-burdel-munecas-barcelona-lumidolls-katy-5882857

32. Rius, M. (2018, mayo 13). ¿El sexo con robots es infidelidad? Edición digital del diario La Vanguardia. Recuperado de https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20180513/443536310487/sexo-robots-infidelidad-munecas.html

33. Bermejo, D. (2018, enero 21). James, el hombre que se acuesta, pasea y cena en restaurantes con su muñeca sexual... con el beneplácito de su mujer. Edición digital del diario El Mundo. Recuperado de https://www.elmundo.es/f5/comparte/2018/01/21/5a62159922601ddb4a8b457c.html

AUTHORS

Isabel Tajahuerce-Ángel: Doctor in Information Sciences. Professor of the Department of Journalism and Global Communication of the Faculty of Information Sciences of the Complutense University. Expert in Communication and gender. Director of the Research Seminar on bioethics, biotechnology, robotics and simulations from a gender and communication perspective. http://www.ucm.es/investigacionsobrebiotecnologiabioeticaroboticaysimulaciones/

isabeltj@ccinf.ucm.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8706-3992

Yanna G. Franco: PhD in Law (Economic analysis of law and institutions). Professor of the Department of Applied, Public and Political Economy of the Faculty of Information Sciences of the Complutense University. Director of the II Robotics and AI Forum with a gender perspective: Sexuality and technology. Director of the Comunicación y Género magazine.

https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CGEN

ygfranco@ucm.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7175-5721

Researcher ID: K-9967-2017