doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.48.45-63

RESEARCH

DOES THE INTENSITY OF SEXUAL STIMULI AND FEMINISM INFLUENCE THE ATTITUDES OF CONSUMERS TOWARD SEXUAL APPEALS AND ETHICAL JUDGMENT? AN ECUADORIAN PERSPECTIVE

¿INFLUYE LA INTENSIDAD DE LOS ESTÍMULOS SEXUALES Y EL FEMINISMO EN LAS ACTITUDES DE LOS CONSUMIDORES HACIA LAS APELACIONES SEXUALES Y EL JUICIO ÉTICO? UNA PERSPECTIVA ECUATORIANA

INFLUE A INTESIDADE DOS ESTIMULOS SEXUAIS E O FEMINISMO NAS ATITUDES DOS CONSUMIDORES COM RESPEITO A LAS APELAÇOES SEXUAIS E O JUIZO ETICO? UMA PERSPECTIVA ECUATORIANA

María D. Brito-Rhor1, Beatriz Rodríguez-Herráez2, Grace P. Chachalo-Carvajal3

1Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain. San Francisco University of Quito. Ecuador.

2Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain.

3San Francisco University of Quito. Ecuador.

ABSTRACT

The objective of this piece of research was to analyze if the attitude toward feminist thought, in a Latin cultural context, influenced the attitude toward different advertisements that used sexual appeals to the body of women. This study was based on theoretical research conducted by Hojoon Choi, Kyunga Yoo, Tom Reichert and Michael LaTour (2016). There were 4 advertisements with various types of sexual appeals: complete nudity, semi-nudity, no nudity and hostile sexism. The results show that the average feminist attitude (M = 3.52, SD = 0.82) is from fair to good and there is a significant difference between men (M = 3.38, SD = 0.87) and women (M = 3.64, SD = 0.77). Women show a slightly more feminist attitude than men. Regarding attitudes to advertisements with different types of sexual content, it was evident that there was a significant difference in the means of ethical attitude towards them. The higher the level of nudity used in the advertisement, the more negative the ethical attitude was. In addition, the average ethical judgment on the ad with “hostile sexism” was significantly different from the ad with semi-nudity and complete nudity. Of the four ads, a significant difference could be found between the feminist attitude and the ethical attitude toward the ad that contained images of hostile sexism. The group with a high degree of feminism had a more negative ethical attitude toward the ad with hostile sexism (M = 3.81, SD = 1.69) compared to the low grade feminism group (M = 4.19, SD = 1.40).

KEY WORDS: attitude, advertisement, nudity, ethical judgment, feminist thinking, sexual advertising, hostile sexism.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar si la actitud hacia el pensamiento feminista, en un contexto cultural latino, influía en la actitud hacia diferentes anuncios publicitarios que utilizaban apelaciones sexuales hacia el cuerpo de la mujer. Este estudio tomó como base teórica las investigaciones realizadas por Hojoon Choi, Kyunga Yoo, Tom Reichert y Michael LaTour (2016). Se mostraron 4 avisos publicitarios con varios tipos de apelaciones sexuales: desnudez completa, semi-desnudez, nada de desnudez y sexismo hostil. Los resultados arrojados muestran que la media de la actitud feminista (M=3.52, SD=0.82) se encuentra de regular a buena y existe una diferencia significativa entre hombres (M=3.38, SD=0.87) y mujeres (M=3.64, SD=0.77). Las mujeres muestran levemente una actitud más feminista que la de los hombres. En cuanto a las actitudes ante los anuncios publicitarios con diferentes tipos de contenido sexual, se evidenció que existía una diferencia significativa de las medias sobre la actitud ética hacia los mismos. Mientras mayor grado de desnudez se utilizaba en el anuncio, la actitud ética era más negativa. Además, la media del juicio ético sobre el anuncio con “sexismo hostil” fue significativamente diferente al anuncio con semi-desnudez y desnudez completa. De los cuatro anuncios se pudo encontrar una diferencia significativa entre la actitud feminista y la actitud ética hacia el anuncio que contenía imágenes de sexismo hostil. El grupo con un alto grado de feminismo tenía una actitud ética más negativa hacia el anuncio con sexismo hostil (M=3.81, SD=1.69) comparado con el grupo de bajo grado de feminismo (M=4.19, SD=1.40).

PALABRAS CLAVE: actitud, anuncio, desnudez, juicio ético, pensamiento feminista, publicidad sexual, sexismo hostil

RESUME

O objetivo desta investigação foi analisar se a atitude com respeito ao pensamento feminista em um contexto cultural latino, influía na atitude com respeito a diferentes anúncios publicitários que utilizavam apelações sexuais diante o corpo da mulher. Esse estudo tomo como base teórica as investigações realizadas por Hojoon Choi, Kyunga Yoo, Tom Reichert e Michael LaTour (2016). Foram mostrados quatro avisos publicitários com vários tipos de apelações sexuais: desnudez completa, semi-desnudez, nada desnudez e sexismo hostil. Os resultados mostram que a média da atitude feminista (M=3.52, SD=0.82) encontrasse de regular a boa e existe uma diferença significativa entre homens (M=3.38, SD=0.87) e mulheres (M=3.64, SD=0.77). As mulheres mostram levemente uma atitude mais feminista que a dos homens. Em quanto as atitudes ante os anúncios publicitários como diferentes tipos de conteúdo sexual, se evidenciou que existia uma diferença significativa das médias sobre a atitude ética aos mesmos. Quanto maior grau de desnudez se utilizava no anúncio, a atitude ética era mais negativa. Ademais, a média do juízo ético sobre o anuncio com “ sexismo hostil” foi significativamente diferente ao anuncio com semi-desnudez e desnudez completa. Dos quatro anúncios pode-se encontrar uma diferença significativa entre a atitude feminista e a atitude ética do anúncio que continha imagens do sexismo hostil. O grupo com um alto grau de feminismo tinha uma atitude ética mais negativa que o anúncio com sexismo hostil (M=3.81,SD=1.69) comparado com o grupo de baixo grau de feminismo (M=4.19, SD=1.40).

PALAVRAS CHAVE: atitude, anúncio, desnudez, juízo ético, pensamento feminista, publicidade sexual, sexismo hostil.

Correspondence: María D. Brito-Rhor: Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain. San Francisco University of Quito. Ecuador.

mbrito@usfq.edu.ec

Beatriz Rodríguez-Herráez: Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain. beatriz.rodriguez@urjc.es

Grace P. Chachalo-Carvajal: San Francisco University of Quito. Ecuador.

pchachalo@estud.usfq.edu.ec

Received: 08/11/2018

Accepted: 21/01/2019

Published: 15/03/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

The first indications of the use of sexual stimuli in advertising date back to the year 1850 (Reichert, 2003). The open use of images with sexual appeal is commonly represented in the advertising of American consumers (Reichert et al., 1999). Several pieces of research argue that the use of sexual content in advertising is used to achieve different objectives such as: attract the attention of the consumer, increase the positive attitude, increase the interest and purchasing intention towards a brand (Belch et al., 1987;, 1990, MacInnis et al., 1991, Percy & Rossiter, 1992, Reichert et al., 2007, Spark & Lang, 2015).

The advertisements are designed in such a way that the models that appear in them must evoke excitement in the target audience (Reichert et al., 2001, Reichert, 2002). Thus, there are several ways in which sexual advertising has attracted attention as is the use of nude models. Nudity is classified by the amount of clothing used by the models or depending on the part of the body that is uncovered (Reichert, 2002). It should be noted that most of the models presented in advertising are female. The proportion of sexualized women increased from less than one third in 1964 to half in 2003 (Soley & Reid, 1988, Reichert & Carpenter, 2004, Nelson & Paek, 2005, Reichert et al., 2012).

At the same time that advertising has used sexual appeals to attract the attention of its public, consumers have also reacted negatively to such stimuli. Various academic pieces of research determine that sexual advertising can also have negative effects in different audiences (Courtney & Whipple, 1983, Gould, 1994, Maciejewski, 2004, Morrinson & Sherman, 1972, Sciglimpaglia, Belch, & Cain, 1979, Alexander & Judd, 1986; LaTour, 1990). One of the reasons is explained by the ethical judgment that each person has. Ethical judgment determines what actions are appropriate out of a set of alternatives; in the advertising context, a person’s ethical judgment will determine whether the use of sexual appeals is an appropriate action or not. Several academic studies determine that certain cultures do not accept sexual advertising because they do not consider it morally correct (Nilaweera & Wijetunga, 2005; LaTour & Henthorne, 1994).

Additionally, feminist movements have questioned advertising about the use of women as sexual objects (Hall & Crum, 1994). According to several researchers, the feminist movement consists of three stages (Offen, 1988, Beasley, 1999, Hawkesworth, 2006). In the first stage, women fight for equal rights, including the right to vote. For example: in the United States the first woman to vote was Susan B. Anthony in 1872; However, in other countries such as Ecuador, the first woman who obtained the right to vote was Matilde Hidalgo de Procel in 1889. Both historical events show that, in nations such as Ecuador, it took longer than 17 years to get the same rights for women. In the second stage, women criticize advertising for the use of their image as an object from a sexual or erotic perspective. However, in the third stage, the members of the feminist movement start appreciating the sexuality of women as an element that must be received and adapted without any kind of taboo (Zimmerman & Dahlberg, 2008; Williams & Jovanovic, 2015). In the third wave of feminism, women are said to take their sexuality as a way of empowerment of their body, so they reject the conventional ways in which their body has been positioned (Gill & Arthurs, 2006; Zimmerman & Dahlberg, 2008). In this stage, women express their sexuality as a shout of rebelliousness and freedom in a men-controlled system to show that men are not the dominant sex (Paglia, 1992; Labi, 1998; Zimmerman & Dahlberg, 2008).

2. OBJECTIVES

A piece of research done in the United States demonstrated that feminist women showed more positive attitudes toward sexual stimuli and had higher levels of sexual satisfaction than non-feminist women (Bay-Cheng & Zucker, 2007). Making reference to this statement, the goal of this piece of research is to investigate whether the attitude toward feminist thinking in a Latin cultural context takes part in the attitude and the ethical judgement toward different ads using sexual appeals.

2.1. Literature review

2.1.1. Sex in advertising

Sexual appeals are defined as an attempt of persuasion through words, images and / or actions carried out by models that appear in advertisements; this way, an explicit or implicit sexual message is delivered. The models are designed to evoke sexual thoughts, feelings and / or excitement in a target audience (Reichert et al., 2001, Reichert, 2002).

The first indications of the use of sexual stimuli in advertising date back to the year 1850. Where, tobacco companies already used naked women in their boxes as a differentiating element from the other brands (Goodrum & Dalrymple, 1990). Over the years, it has become clear that the use of eroticism in advertising has been increasing in tone and is becoming more explicit, so, for example, the advertising of R & G Corsets was censored by some media in 1898; and if we compare it with the advertisements of today, they are very far in terms of sexual explicitness. The first brand to violate the taboo of showing ads in mass media, showing buttocks and penises, was Calvin Klein in 1983 with his lingerie campaign (Reichert & Lambiase, 2012). According to several pieces of research, brands use sexual appeals as stimuli to boost their personality and / or increase their sales (Belch et al., 1987, LaTour, 1990, MacInnis et al., 1991, Percy & Rossiter, 1992, Reichert et al., 2007; Spark & Lang, 2015). Although sex in advertising has been a controversial issue; it is used naturally in products such as cosmetics, perfumes or fashion accessories. For example, in magazine advertising; the proportion of sexualized women increased from less than one third in 1964 to half in 2003 (Soley & Reid, 1988, Reichert & Carpenter, 2004, Nelson & Paek, 2005, Reichert et al., 2012). Various pieces of research analyze the types of sexual appeals that may exist in advertising. These appeals may include nudity, behavior, physical attractiveness, and sexual innuendo (England & Gardner, 1983, Soley & Reid, 1988, Reichert et al., 1999).

Nudity is when one or several parts of the body of a person are not covered with clothing (Soley & Reid, 1988). In the world of advertising, one of the simplest ways to arouse a sexual appeal is through the position and quantity of clothes in the models (Soley & Reid, 1988). Soley and Reid (1988) proposed a typology for classifying nudity in ads that have often been used as a basis for developing experimental stimuli. The typology is divided into four: 1. Demure (daily clothes), 2. Suggestive (miniskirts, shorts), 3. Partially dressed (swimsuits) and 4. Nudity (silhouettes of models either nude or wearing only a towel up to complete nudity). Even the only exposure of the buttocks and / or breasts is already considered as nudity, since the presence of complete nudity in advertisements is rare (Reichert, 2002).

Similarly, Reichert (2002) states that sexual appeals can also occur through actions of one or several models together. These models participate in explicit or implicit behaviors that show sexual activity, interest or availability (Reichert, 2002). As for explicit behaviors, they can be seen reflected; for example, when a woman touches her breasts in a sexual way (Yang et al., 2010), when a couple - male and female - kiss or hug each other (Garcia & Yang, 2006; Huang, 2004; Pope et al., 2004); or sexual positions that resemble intercourse (Cheung et al., 2013; Severn et al., 1990; So, 1996). On the other hand, implicit sexual appeals are included; for example, behaviors such as the use of provocative clothing by a heterosexual couple (Reichert & Alvaro, 2001), a suggested pose that shows a sexual opportunity (Patzer, 1980, Reichert et al., 2007) or fabricating a scenario in which it is denoted that a couple is going to have an imminent sexual encounter (Horton et al., 1982, Mittal & Lassar, 2000, Reichert & Fosu, 2005).

Together, the attractiveness of the models used in advertisements is another form of engagement by advertising. Because the attractive models are perceived in a better way as compared to the models that are not attractive (Snyder & Rothbarth, 1971, Horai et al., 1974, Joseph, 1982). Studies show that attractive faces instantly produce a positive sensation in the viewer; and the appearance is consciously associated with an inherent “kindness” that is then related to the product (Smith & Engel, 1968, Joseph, 1982). In this quality, the sex of the models does not matter; physical attractiveness works persuasively and the signal it emits is pervasive and difficult to ignore, so the advertisement is easily recognized (Chaiken, 1972, Joseph, 1982, Baker & Churchill, 1977).

On the other hand, sexual innuendo is a type of erotic attraction that uses words, images and / or actions of models to deliver a message that can be interpreted as a sexual or non-sexual act (Reichert, 2002). As a result, ads that use sexual advances require the audience to recognize the erotic interpretation of the ad to be effective. For example, in a Burger King ad in which you see a woman holding a sandwich near her open mouth with the headline: “Your mind will fly”, the pose of the model combined with the headline could be interpreted as a reference to oral sex.

Based on the foregoing, the emotional nature of sexual information in advertising plays an important role in processing, evaluation and persuasion. Evidence indicates that sexual information attracts attention, is interesting and attractive. However, this appeal does not guarantee product acquisition or brand recognition (Reichert et al., 2001).

2.1.2. Ethical judgment on sex in advertising

Despite knowing the potential of an ad with sexual content, several academic pieces of research have warned advertisers about the negative consequences that can be generated by the use of this type of appeals (Courtney & Whipple, 1983). Gould (1994) explains that the use of sexual appeals in advertising, to certain people in a target segment, could rather produce a rejecting effect. That is, the use of sexual appeals can be met with disdain and negative evaluations, since consumers judge the appeal to be morally incorrect (Gould, 1994, Maciejewski, 2004, Morrinson & Sherman, 1972, Sciglimpaglia, Belch, & Cain, 1979; Alexander & Judd, 1986; LaTour, 1990). Then, the use of sexual content in advertising is used and perceived differently depending on the culture to which the stimulus is presented (Bochner, 1994).

In the American culture, open sexual appeals are very common (Reichert et al., 1999; Soley & Reid, 1988) and, in general terms, they are well received (Belch et al., 1987, Percy & Rossiter, 1992). In 1871, one of the earliest examples of sexual advertising appears; when the cigarette brand “Pearl Tabacco” includes the illustration of a partially naked woman in the packs of its products (Reichert & Lambiase, 2003).

In Europe, there are studies in which it is shown that, in countries like France, the use of sexual stimuli are perceived as glamorous archetypes and, at the same time, they have great openness to sexual expressions. Biswas, Olsen and Carlet (1992) stated that French advertising has more sexual appeals than American advertising. 24% of French advertising used sexual appeals as compared to 8.6% of American. That is, the French culture is more open to receive advertising with sexual appeals (Biswas et al., 1992).

However, Sawang (2010) conducted a piece of research on the acceptance of sexual advertising between the Asian and the American culture. The results of this study concluded that the Asian culture was less receptive to sexual advertising as compared to the American culture. All this could be explained through the ethical judgment of the people. The ethical judgment of the human being has two dimensions: moral / relativist equity and contractualism (Reidenbach & Robin, 1990). In the current context, the dimension of moral / relativist equity refers to the extent to which a sexual appeal is considered correct or incorrect according to the moral equity and social guidance of an individual (LaTour & Henthorne, 1994). These guides are fostered through the life of the individual and are very influenced by social institutions such as family, religion and school (Reichert et al., 2011). That is, the moral / relativistic equity dimension of an individual evaluates to what extent the morality of sexual advertising falls within the parameter or guideline manifested by social institutions (LaTour & Henthorne, 1994, Reichert et al., 2011). On the other hand, the dimension “Contractualism” refers to the extent to which sexual attractiveness violates a tacit / unwritten social contract between the individual and society (LaTour & Henthorne, 1994, Reidenbach & Robin, 1990). In predicting consumer responses to sexual advertisements, studies consistently show that moral / relativistic equity is a dimension much stronger than the dimension of contractualism because the former dimension reflects the feelings of consumers about the degree of adequacy in advertising; while the latter dimension is not related to specific ethical evaluations of advertisements (LaTour & Henthorne, 1994; Reichert et al., 2011).

2.1.3. El Feminism and sexual advertising

Feminism is defined as the set of beliefs that support gender equality. This equality should be reflected in different areas such as: political, economic, cultural, personal and social rights (Beasley, 1999, Hawkesworth, 2006). For a long time, this movement has influenced the thinking of people (Messer-Davidow, 2002, Zimmerman & Dahlberg, 2008).

The history of feminism is framed in three stages: the first stage occurs from the nineteenth to the early twentieth century, feminism of the second stage in the middle of the 20th century and feminism of the third stage since the end of the 20th century (Humm, 1995); Freedman, 2003). Whereas feminism of the first stage focused mainly on the equality of property and the right of women to vote; feminism of the second stage extended the issue of equality to sexuality, family, work, among other topics (Freedman, 2003). With respect to sexuality, feminists of the second stage emphasized the notion that women are victims of a male-dominated society (Paglia, 1992; Krolokke & Sorensen, 2005). Adherents expressed themselves against stereotyped femininity and sexual practices and criticized the depiction of women’s sexuality in the media as “sexist pop culture” and “instruments of oppression” (Arrow, 2007, Baumgardner & Richards, 2010; Jovanic, 2015) Feminism of the second stage declares that the desire and sexual pleasure of women is considered a “non-feminist” act (Williams & Jovanovic, 2015). On the other hand, feminism of the third stage explains the empowerment of women’s sexuality, here desire and pleasure are considered a natural part of femininity, in this sense, feminism of the third stage is more open and positive towards sexuality and sexual practices of women because they use sexual self-efficacy to communicate their sexual needs and independence (Curtin et al., 2011), that is, feminism of the third stage reflects sexuality as a means of female empowerment (Gill & Arthurs, 2006; Holt & Cameron, 2010) and empowered sexuality contributes to female sexual liberation while rejecting conventional standards of sexuality (Zimmerman & Dahlberg, 2008; Williams & Jovanic, 2015).

From the third stage of feminism; from the advertising point of view, women with open sexual attitudes showed preference for ads with sexual content and a more favorable ethical judgment as compared to the preferences of less feminist groups (Sengupta & Dahl, 2008).

3. METHODOLOGY

The objective of this piece of research was to analyze whether the attitude toward feminist thought, in a Latin cultural context, influenced the attitude and ethical judgment towards different advertisements that used sexual content. The theoretical and methodological foundation of this study was the pieces of research conducted by Hojoo Choi, Kyunga Yoo, Tom Reichert and Michael S. LaTour (2016).

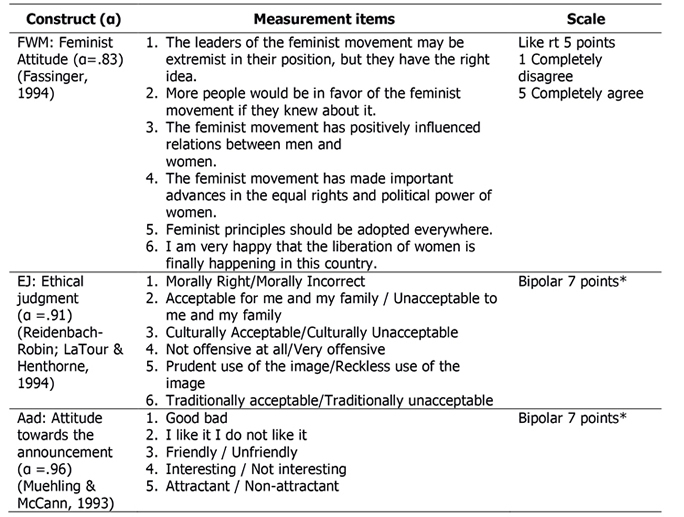

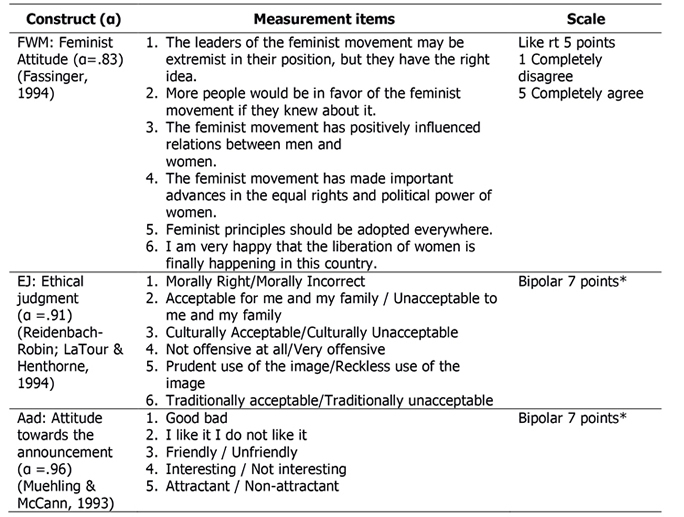

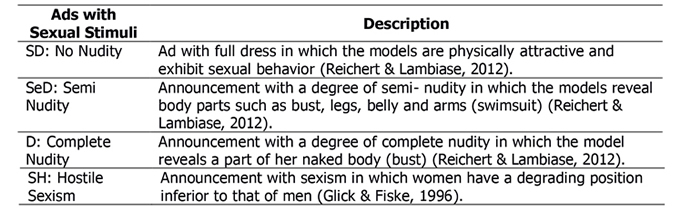

The sampling technique we used was that of non-probabilistic convenience. The survey was applied personally, using mobile devices to complete it. In April 2018, 249 people, men and women of Ecuadorian nationality, aged 16 to 59 years, were surveyed. The attitude towards the feminist movement was qualified by means of a measuring instrument, called “Attitudes towards feminism and the women’s movement” (FWM), developed by Fassinger (1994) (Table 1). Next, 4 advertisements with various types of sexual appeals were shown: complete nudity, semi-nudity, no nudity and hostile sexism (Table 2). For each advertisement, the ethical judgment was measured, using Reidenbach-Robin construct (LaTour & Henthorne, 1994), as the attitude towards sexual stimulus, using the Muehling & McCann construct (1993).

Table 1: Construct, measurements and scales.

Source: Own elaboration.

* Note: Recoded so that higher values are better judgment and/or attitude.

Table 2: Description of sexual advertising stimuli.

Source: Own elaboration.

3.1. Procedure

The process of the experiment began with a survey which was divided into three parts. In the first part, participants answered demographic questions such as their gender, age, nationality and marital status. In the second part they were given a questionnaire to measure their level of feminism. Then they were able to view four advertisements, all of which contained sexual appeals. The marks used in the experiment are real and not fictitious; because they increase external validation (Choi et al., 2013). Likewise, brands such as Dolce & Gabbana and Tom Ford were chosen because they are brands recognized for their high sexual appeal in their advertisements (LaTour, 1990, Soley & Reid, 1988).

After each advertisement, they were asked how they felt when viewing the image in order to measure their attitudes towards the advertisement and subsequently they were asked to fill in a bipolar scale of 7 points in order to measure their ethical judgment. Finally, the collected information served for the analysis of the presented hypothesis about whether feminist thinking affects the way of perceiving an advertisement with sexual content and in the same way analyze the perception of Ecuadorians through their ethical judgment.

4. DISCUSSION

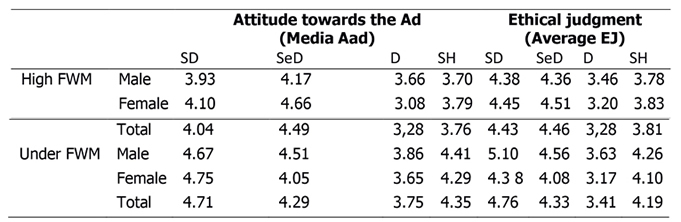

The results show that the average feminist attitude (M = 3.52, SD = 0.82) is from fair to good and there is a significant difference between men (M = 3.38, SD = 0.87) and women (M = 3.64, SD = 0.77), t (247) = - 2.52, p = .01. Women show a slightly more feminist attitude than men. Regarding the attitudes towards advertising with different types of sexual content, it was evident that there was a significant difference of the means on the ethical attitude towards them. The average of the ethical judgment on the ad with hostile sexism (M = 4.02) was significantly different from the ad without nudity (M = 4.65, p <0.00), semi-nudity (M = 4.45 p <0.00) and complete nudity (M = 3.41 p <0.00). It should be noted that, with the exception of the advertisement with complete nudity, the ethical judgment of the advertisement with hostile sexism was more negative when compared with the other advertisements (Table 3).

Table 3: Differences of means.

Source: Own elaboration.

*Note: Higher numbers indicate a better attitude towards the advertisement and a better ethical judgment. FWM: in English for the scale of “Attitudes towards Feminism and the Movement of Women”. SD: Without Nudity; SeD: Semi Nudity; D: Complete Nudity; SH: Hostile Sexism.

Of the four ads, a significant difference could be found between the feminist attitude and the ethical attitude toward the ad that contained images of hostile sexism. The group with a high degree of feminism had a more negative ethical attitude toward the ad with hostile sexism (M = 3.81, SD = 1.69) as compared to the low grade feminism group (M = 4.19, SD = 1.40). Likewise, a significant relationship was found (χ² (2, n = 152) = 6.938, p =, 031) between the degree of feminism and the attitude towards the advertisement: for the case of the advertisement with “hostile sexism” against women. This indicates that the most feminist people had a more negative attitude towards this type of ads as compared to less feminist individuals.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The objective of this study was to analyze whether the attitude towards feminist thought (FWM), in a Latin American cultural context, influenced both the attitude toward different advertisements (Aad) advertising that contained sexual stimuli and the ethical judgment towards them (EJ).

It corroborates the finding of previous research that indicates that there is a negative relationship between feminist attitudes and the use of sexuality in advertising (Ford & LaTour, 1993). That is, the more feminist groups had more negative attitudes especially towards the ad that contained hostile sexism. It has not been possible to corroborate the positive relationship of the third wave of feminism with the perception of female sexuality as a tool of empowerment; so it could be inferred that the sample belongs to the second wave of feminism. This trend emphasized women as victims of a society dominated by machismo where their body is treated as a sexual object.

It was evident that the feminist attitude of men and women was on a fair to good level. However, women showed a more feminist attitude than men. Additionally it was shown that the greater the degree of nudity in the advertisement, the more negative the ethical judgment was. Contrary to the findings of Choi et al. (2016), the group with a high degree of feminism had a more negative ethical judgment towards the ad with hostile sexism than the group with a less feminist attitude.

As with other variables of individual differences in personality, such as the female sexual self-schema (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994), attitudes towards Feminism and the Women’s Movement influence the attitude towards advertisement with sexual information. These psychological differences of individual traits between consumer groups are important for better market segmentation. Precisely, one of the essential concepts of Strategic Marketing, especially in a highly competitive environment, is the market segmentation that establishes that different types of consumers have different needs. Thus, for several ads we will also see different behaviors depending on the characteristics of the individual. For example, the ad with hostile sexism underwent much more marked rejection that came from the group with a high degree of feminism. Therefore, this type of advertisements with hostile sexism and feminine submission poses should be avoided. Even in several countries, this type of hostile sexist discrimination towards women is already illegal (Garaigordobil & Aliri, 2011).

In short, the positive or negative attitudes of pro-feminist groups will depend on the type of sexual content of the advertisements. Finally, it is suggested that, for future research, different age and geographical groups be selected in order to reach a more precise approach in different study segments. Also, future studies could extend this knowledge to different categories of products and/or services.

REFERENCES

1. Alexander, M., & Judd, B. (1986). Differences in attitudes toward nudity in advertising. Psychology: A Quarterly Journal of Human Behavior, 23(1), 26-29. doi: EJ338629

2. Andersen, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1079–1100. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1079

3. Arrow, M. (2007). “It has become my personal anthem” “I am woman”. Popular culture and 1970s feminism. Australian Feminist Studies, 22(53), 213-30. doi: 10.1080/08164640701361774

4. Baker, M., & Churchill, A. (1977). The Impact of Physically Attractive Modelson Advertising Evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(4), 538-555. doi: 10.2307/3151194

5. Baumgardner, J., & Richards, A. (2010). Manifesta: Young women, feminism, and the future. New York , NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

6. Bay-Cheng, L., & Zucker, A. (2007). Feminism between the sheets: Sexual attitudes among feminists, nonfeminists, and egalitarians. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 31(2). 157-163. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00349.x

7. Beasley, C. (1999). What is feminism? An introduction to feminist theory. London: Sage.

8. Belch, G., Belch, M., & Villareal, A. (1987). Effects of advertising communications: Review of research. Research in Marketing, 9, 59 - 117.

9. Biswas, A.; Olsen, J., & Carlet, V. (1992). A comparison of print advertisements from the United States and France. Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 73-81. doi: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4188859

10. Bochner, S. (1994). Cross culture differences in self-concept: A test of Hoftede´s individualis/collectivism distinction. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 25(2), 273-283. doi: 10.1177/0022022194252007

11. Chaiken, S. (1972). Communicator Physical Attractiveness and Persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(8), 1387-1397. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.8.1387

12. Cheung, M.; Chan, A., & Han, Y. (2013). Differential effects of Chinese women´s sexuality self-schema on responses to sex appeal in advertising. Journal of Promotion Management, 19(3), 373-391. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2013.787382

13. Choi, H.; Yoo, K., Reichert, T., & LaTour, M. S. (2016). Do feminists still respond negatively to female nudity in advertising? Investigating the influence of feminist attitudes on reactions to sexual appeals. International Journal of Advertising, 35 (5), 823-845. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2016.1151851

14. Courtney, A., & Whipple, T. (1983). Sex stereotyping and advertising. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

15. Curtin, N.; Ward, M.; Merriwether, A., & Caruthers, A. (2011). Femininity ideology and sexual health in young women: A focus on sexual knowledge, embodiment, and agency. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(1), 48-62. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2010.524694

16. England, P., & Gardner, T. (1983). Sex differentiation in magazine advertisements: A content analysis using log-linear modeling. Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 6(1), 253- 268. doi: 10.1080/01633392.1983.10505342

17. Fassinger, R. E. (1994). Development and Testing of the Attitudes Toward Feminism and the Women’s Movement (FWM) Scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18(3), 389–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00462.x

18. Freedman, E. (2003). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

19. Garcia, E., & Yang, K. (2006). Consumer responses to sexual appeals in cross-cultural advertisements. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19(2), 29-52. doi: 10.1300/J046v19n02_03

20. Gill, R., & Arthurs, J. (2006). Editors’ introduction: New femininities? Feminist Media Studies, 6(4), 443-451. doi: 10.1080/14680770600989855

21. Goodrum, C., & Dalrymple, H. (1990). Advertising in America: The First Two Hundred Year. New York: Harry N Abrams Inc.

22. Gould, S. (1994). Sexuality and ethics in advertising: A framework and research agenda. Journal of Advertising, 23(3), 73-80. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1994.10673452

23. Hall, C., & Crum, M. (1994). Women and “Body-isms” in television beer commercials. Sex Roles, 31(329). doi: 10.1007/BF01544592

24. Hawkesworth, M. (2006). Globalization and feminist activism. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

25. Holt, D., & Cameron, D. (2010). Cultural strategy: Using innovative ideologies to build break-through brands. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

26. Horai, J., Naccari, N., & Fatoullah, E. (1974). The Effects of Expertise and Physical Attractiveness on Liking, Sociometry, 37(4), 601-606. doi: 10.2307/2786431

27. Horton, R., Lieb, L., & Hewitt, M. (1982). The effects of nudity. suggestiveness and attractiveness on product class and name recall. En R. Horton, L. Lieb, & M. Hewitt, Developments in marketing science. p.p 456-9. Nacogdoches, TX: Academy of Marketing Science.

28. Huang, M. (2004). Romantic love and sex: Their relationship and impacts on ad attitudes. Psychology & Marketing, 21, 53-73. doi: 10.1002/mar.10115

29. Humm, M. (1995). The dictionary of feminist theory. Columbus, OH: Ohio Statae University Press.

30. Joseph, W. (1982). The Credibility of Physically Attractive Communicators: A Review. Journal of Advertising, 11(3), 15-24. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1982.10672807

31. Krolokke, C., & Sorensen, A. (2005). Gender communication theories and analysis: From silence to performance. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

32. Labi, N. (1998). Feminism: Girl Power. Time 151, 25, 60-2.

33. LaTour, M. (1990). Female nudity in print advertising: An analysis of gender differences in arousal and AD response. Psychology & Marketing, 7, 65-81. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220070106

34. LaTour, M., & Henthorne, T. (1994). Ethical judments of sexual appeals in print advertising. Journal of Advertising, 23(3), 81-90.

35. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1994.10673453

36. Maciejewski, J. (2004). Is the use of sexual and fear appeals ethical? A moral evaluationby generation Y college students. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 26(2), 97-105. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2004.10505167

37. MacInnis, D.; Moorman, C., & Jaworski, B. (1991). Enhacing and measuring consumers´ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. Journal of Marketing, 55(4), 32 - 53. doi: 10.2307/1251955

38. Messer-Davidow, E. (2002). Discipling feminism: From social activism to academic discourse. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

39. Mittal, B., & Lassar, W. (2000). Sexual liberalism as a determinant of consumer response to sex in advertising. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15(1), 111-27. doi: 10.1023/A:1007723003376

40. Morrinson, B., & Sherman, R. (1972). Who responds to sex in advertising?, Journal of Advertising Research, 12(2), 15 - 9.

41. Muehling, D. D. & McCann, M. (1993). Attitude toward the Ad: A Review. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 15(2), 25–58. doi: 10.1080/10641734.1993.10505002

42. Nelson, M., & Paek, H. (2005). Predicting cross-cultural differences in sexual advertising contents in a transnational woman´s magazine, Sex Roles, 53(5-6), 371 – 83. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-6760-5

43. Nilaweera, U., & Wijetunga, D. (2005). The impact of cultural values of the effectiveness of television commercials with female sexual appeal: A Sri Lankan study. South Asian Journal of Management, 12(3), 7-20.

44. Offen, K. (1988). Defining feminism: A comparative historical approach. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 14(1), 119-157.

45. Paglia, C. (1992). Sex, art, and American culture. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

46. Patzer, G. (1980). A comparison of advertisement effects: Sexy female communicator vs non-sexy female communicator, en G. Patzer, Advances in consumer research, p.p. 359-64. San Francisco, CA: Association for Consumer Research.

47. Percy, L., & Rossiter, J. (1992). A model of brand awareness and brand attitude advertising strategies. Psychology & Marketing, 9, 263-274. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220090402

48. Pope, N.; Voges, K., & Brown, M. (2004). The effect of provocation in the form of mild erotica on attitude to the ad and corporate image. Journal of Advertising, 33(1), 69-82. doi: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4189247

49. Reichert, T. (2002). Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. Annual review of sex research, 13, 241-73. doi: 10.1080/10532528.2002.10559806

50. Reichert, T. (2003). The Erotic History of advertising. New York: Prometheus.

51. Reichert, T., & Alvaro, E. (2001). The effects of sexual information on ad and brand processing and brand processing and recall. International Journal of Advertising, 37(2), 168-198. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2017.1334996

52. Reichert, T., & Carpenter, C. (2004). Un update on sex in magazine advertising, 1983 to 2003. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 823–837. doi: 10.1177/107769900408100407

53. Reichert, T., & Fosu, I. (2005). Women´s responses to sex in advertising: Examining the effects of women´s sexual self-schema on responses to sexual content in commercials. Journal of Promotion Management, 11(2-3), 143-15. doi: 10.1300/J057v11n02_10

54. Reichert, T., & Lambiase, J. (2003). Sex in advertising: Perspectives on the erotic appeal. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

55. Reichert, T., & Lambiase, J. (2012). Sex in advertising Perspectives on the Erotic Appeal. New York: Routledge.

56. Reichert, T.; Childers, C., & Reid, L. (2012). How sex in advertisins varies by product category: An analysis of three decades of visual sexual imagery in magazines advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 33(1), 1-19. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2012.675566

57. Reichert, T.; Heckler, S., & Jackson, S. (2001). The effects of sexual social marketing appeals on cognitive processing and persuasion, Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 13-27. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2001.10673628

58. Reichert, T.; Lambiase, J.; Morgan, S., Zaviona, S., & Carstarphen, M. (1999). Cheesecake and Beefcake: No Matter How You Slice it, Sexual Explicitness in Advertising Continues to Increase. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(1), 7–20. doi: 10.1177/107769909907600102

59. Reichert, T.; LaTour, M., & Ford, J. (2011). The naked truth revealing the affinity for graphic sexual appeals in advertising. Journal of Advertising Research , 51, 436-48. doi: 10.2501/JAR-51-2-436-448

60. Reichert, T.; LaTour, M., & Kim, J. (2007). Assessing the influence of gender and sexual self-schema on affective response to sexual content in advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 29(2), 63-77. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2007.10505217

61. Reidenbach, R., & Robin, D. (1990). Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 639-53. doi: 10.1007/BF00383391

62. Sawang, S. (2010). Sex Appeal in advertising: What Consumers Think. Journal of Promotion Management. 16(1-2), 167-187. doi: 10.1080/10496490903578832

63. Sciglimpaglia, D., Belch, M., & Cain, R. (1979). Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 6). (W. Wilkie, Ed.) Miami, Florida: Association for Consumer Research.

64. Sengupta, J., & Dahl, D. (2008). Gender-related reactions to gratuitous sex appeals in advertising. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18, 62-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2007.10.010

65. Severn, J.; Belch, G., & Belch, M. (1990). The effects of sexual and non-sexual advertising appeals and information level on cognitive processing and communication effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 14-22. doi: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4188751

66. Smith, G., & Engel, R. (1968). Influence of a Female Model on Perceived Characteristics of an Automobile. Proceedings of the 76th American Psychological Association Annual Convention, (p. 681-682).

67. Snyder, M., & Rothbarth, M. (1971). Communicator Attractiveness and Opinion Change. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 3(4), 377-387. doi: 10.1037/h0082280

68. So, S. (1996). Does sex sell in Chinese society? An empirical study. Brain and language, 79-94.

69. Soley, L., & Reid, L. (1988). Taking it off: Are models in magazine ads wearing less? Journalism ans Mass Communication Quarterly, 65(4), 960 - 6. doi: 10.1177/107769908806500419

70. Spark, J., & Lang, A. (2015). Mechanisms underlying the effects of sexy and humorous content in advertisements. Communication Monographs, 82(1), 134-162. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2014.976236

71. Williams, J., & Jovanic, J. (2015). Third wave feminism and emerging adult sexuality: Friends with Benefits Relationships. Sexuality and Culture, 19(1), 157-71. doi: 10.1007/s12119-014-9252-3

72. Yang, R.; Ogle, J., & Hyllegard, K. (2010). The impact of message appeal and message source on Gen Y consumers´ attitudes and purchase intentions toward American apparel. Journal of Marketing Communications, 16(4), 203-224. doi: 10.1080/13527260902863221

73. Zimmerman, A., & Dahlberg, J. (2008). The sexual objectification of women in advertising: A contemporary cultural perspective. Journal of Advertising Research, 48(1), 71-9. doi: 10.2501/S0021849908080094

AUTHORS

Maria D. Brito-Rhor: PhD(c) in Social and Legal Sciences, Rey Juan Carlos University. MBA specialization in Marketing and Finance, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile / Indiana University. BSBA specialization in Strategic Marketing, University of North Carolina, USA. For more than 15 years, she has worked as a full-time professor at the San Francisco de Quito University in several chairs of Business Administration, Marketing and Advertising Communication. Some of his lines of research are consumer behavioral psychology, consumer neuroscience, digital marketing among others. It has more than thirty publications on topics related to marketing. In addition, he directs the Digital Marketing Department of the San Francisco University of Quito.

mbrito@usfq.edu.ec

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0385-0620

Beatriz Rodríguez-Herráez: PhD in Marketing from the Complutense University of Madrid and full professor hired by the Rey Juan Carlos University.

beatriz.rodriguez@urjc.es

Grace P. Chachalo-Carvajal: Research assistant and student of the Advertising Communication career at the San Francisco University of Quito.

pchachalo@estud.usfq.edu.ec