10.15198/seeci.2018.47.01-15

RESEARCH

FILM POETRY. RETHINKING THE AVANT-GARDE CINEMA: ART IN MOTION AND VISUAL POETICS

FILM POETRY. REPENSANDO EL CINE DE VANGUARDIA: ARTE EN MOVIMIENTO Y POÉTICAS VISUALES

FILME POETRY. REPENSANDO O CINEMA DE VANGUARDA: ARTE EM MOVIMENTO E POÉTICAS VISUAIS

Virginia Villaplana-Ruiz1 University of Murcia. Department of Fine Arts. Spain.

Pedro Ortuño-Mengua1

1University of Murcia. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article has a first objective, to group the avant-garde film in three big variables aesthetic, as abstraction, “Film-poem as abstraction”, “Film poetry as analytical model” and “Film as dialectic poetry”, related to critical theories and writings of the filmmakers themselves. This paper on the one hand analyzes the poetics of Abel Gance, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L’Herbier, Jean Epstein, Louis Delluc, Marcel Duchamp, Walter Ruttmann, Man Ray and Dziga Vertov. A second objective would be the review of the notion of avant-garde cinema is reviewed by the contributions of the film theory developed by Jean Mitry, Bill Nichols, Malcolm Turvey, Vicente Sánchez-Biosca and Carlos Tejeda among others. These authors allow us to approach methodologically the diferente dimensions that characterize Film-poem As abstraction, analytical model and dialectical poetry. These aesthetic and philosophical ideals are linked to the experiences of the plastic arts and contemporary art. In the same way, this article exposes the poetic conception of the vanguard movement interrelating film works of the experimental art from models of representation.

KEY WORDS: film poetry; art; avant-garde; aesthetic strategies; film theory; experimental cinema; cinematographic history

RESUMEN

Este artículo tiene como primer objetivo, agrupar las vanguardias artísticas cinematográficas en tres grandes variables estéticas, “Film-poem como abstracción”, “Film poetry como modelo analítico” y “Film como poesía dialéctica”, relacionadas con las teorías críticas y los escritos de los propios cineastas. Por una parte se analizan las poéticas de Abel Gance, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L´Herbier, Jean Epstein, Louis Delluc, Marcel Duchamp, Walter Ruttmann, Man Ray y Dziga Vertov. Un segundo objetivo sería el repaso de la noción de cine de vanguardia mediante las aportaciones de la teoría fílmica elaboradas por Jean Mitry, Bill Nichols, Malcolm Turvey, Vicente Sánchez-Biosca, Bruce Elder y Carlos Tejeda entre otros. Dichos autores nos permiten abordar metodológicamente las distintas dimensiones que caracterizan el Film-poem como abstracción, modelo analítico y como poesía dialéctica. Estos ideales estéticos y filosóficos están vinculados a las experiencias de las artes plásticas y del arte contemporáneo. Del mismo modo, este artículo expone la concepción poética del movimiento de vanguardia interrelacionando obras fílmicas del arte experimental a partir de modelos de representación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: film poético; arte; vanguardia; teoría fílmica; estrategias estéticas; cine experimental; historia cinematográfica

RESUME

Este artigo tem como primeiro objetivo, agrupar as vanguardas artísticas cinematográficas em três grandes variáveis estéticas, “Film-poem como abstração” “Film poetry como modelo analítico” e “Film como poesia dialética”, relacionadas com as teorias críticas e os escritos dos próprios cineastas. Por uma parte se analisam as poéticas de Abel Gance, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L´Herbier, Jean Epstein, Louis Delluc, Marcel Duchamp, Walter Ruttmann, Man Ray e Dziga Vertov. Um segundo objetivo seria o repasso da noção de cinema de vanguarda mediante as contribuições da teoria fílmica elaboradas por Jean Mitry, Bill Nichols, Malcolm Turvey, Vicente Sanchez-Biosca, Bruce Elder e Carlos Tejeda entre outros. Tais autores nos permitem abordar metodologicamente às distintas dimensões que caracterizam o Film-poem como abstração, modelo analítico e como poesia dialética. Estes ideais estéticos e filosóficos esta vinculados às experiências das artes plásticas e da arte contemporânea. Do mesmo modo, este artigo expõe a concepção poética do movimento de vanguarda inter-relacionando obras fílmicas da arte experimental a partir de modelos de representação.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: film poético; arte; vanguarda; teoria fílmica; estratégias estéticas; cine experimental; história cinematográfica

Correspondence: Virginia Villaplana Ruiz: University of Murcia. Spain

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5033-5325

virginia.villaplana@um.es

Pedro Ortuño Mengual: University of Murcia. Spain

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9953-5739

pedrort@um.es

Received: 15/05/2018

Accepted: 30/07/2018

How to cite the article

Villaplana Ruiz, V. y Ortuño Mengual, P. (2018). Film Poetry. Rethinking avant-garde cinema: art in motion and visual poetics. [Film Poetry. Repensando el cine de vanguardia: arte en movimiento y poéticas visuales] Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 01-15. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.47.01-15

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/516

1. INTRODUCTION

In the texts that Germaine Dulac wrote in her book The Avant-Garde Cinema, the author proposes the study of visual forms to try to define a series of rules or proofs in works of pure or absolute avant-garde cinema. Some of these rules would be related to the analysis of the cinematographic work, to study if the expression of the movement depends on the rhythm, if it should reject any esthetic principle that does not belong to it looking for its own esthetic or that the cinematographic action must be alive without limited exclusively to the human figure, extending beyond the realm of nature and dreams (Dulac 1987, p.47). We provide in an initial section, a study of the important work done by Jean Mitry and his critique, focused essentially on the linguistic aspect of the cinema of the vanguards, trying to create a kind of harmony between the realistic and formalist positions, with conciliatory intentions or of compromise.

2. OBJECTIVES

We consider it important to combine the different movements of the cinematographic vanguards into categories defined by common aspects in relation to the identification of the new with the good, the need to move towards the future from the art world, the establishment of the rupture of the tradition and the certainty that the creation of a product was condemned to immediate overcoming. For this reason, the main objective of this study is methodologically the avant-garde cinema grouped into three major esthetic variables that influence the filmic conception of the works, of their own texts and authors:

1. “Film-poem as an abstraction or from French impressionism to pure cinema”,

2. “Film poetry as an analytical model”

3. “Film as poetry Advances in Social Science Education and Humanities” Research dialectic.”

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve the marked objective, we have used a mixed research method that responds to a combination of quantitative and qualitative techniques and thus give greater value to the research since both complement each other. Methodologically, the first of these aforementioned esthetic variables “Film-poem as an abstraction or from French impressionism to pure cinema” revolves around a group of filmmakers who would be essential, according to Louis Delluc, in the evolution of French cinematography and connected with Dadaism and Cubism (Turvey 2013). A cinema that moves away from the plot, script, story or narration in favor of its own image as an expressive medium. Most of its representatives come from the field of plastic arts.

The second variable “Film poetry as analytical model” would be related to the expressionism, as documented very well by Sánchez-Biosca (1990) in his studies on the cinema of the Weimar Republic and its models and characteristics of representation. We also find authors who do not shoot films making cinematographic collages, according to the ready-made proposed by Duchamp, from films already shot for other purposes, and inspired by the artistic avant-garde of the early twentieth century.

The third and last of the variables deals with “Film as dialectical poetry “. We find filmmakers who theorize about their own conception of cinema and propose models of representation based on the methods of editing according to the modern techniques of fragmentation and juxtaposition that gave an artistic aura to the documentary genre, addressing issues of public importance by contradicting or reaffirming the State role in these issues (Nichols 2001, p. 582).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The critical thinking of Jean Mitry. Avant-garde cinema and subversion of reality

Jean Mitry is a contemporary of the first experiments of the French avant-garde. His work is inserted in the ontological theories about cinema, trying to define the essence of cinema in a global way. Mitry’s case focuses essentially on the linguistic aspect, creating a kind of harmony between the realistic and formalist positions, are conciliatory, commitment positions. In his work, a systematic treatment of cinema is found; Bazin reflected extemporaneously. Mitry was the first professor of cinema with a recognized academic function, although he acted outside the university system.

From its beginnings, the reflection on the cinema is lacking in specificity, it is done from other perspectives and disciplines. Mitry founded together with Langlois and Franju the French Cinematheque in 1938, which has a fundamental role in the deployment of film clubs and allows the French to watch American films after the Second World War (banned from Vichy) and the classics.

Mitry is present in the creation of Institute of Filmology, the International Journal of Filmology and the Magazine Cahiers du cinéma, all these essential moments, with him the cinema acquires an institutional and academic legitimacy. In his 1973 texts he reflects on film-painting relations, the cinematographic medium, colors, lines. It establishes levels of reception and interpretation proposing the constitution of a filmic sense:

1. Perceptive of that double reality.

2. The narration, syntagmatic sequence of the images; the human being cannot be avoided. The images, in relation to a real world, create a new model.

3. Poetic and abstract meaning, beyond the obvious meaning that differentiates artistic perception from common. With this meaning, the sense is freed from the bonds of perception.

For Mitry (1973) the image is an analogy of reality, but cannot be identified with it. From that premise, he explicit the particularities of the image:

1. To resemble the real. To present something that is thought immediately intuitive, the intention would be to show more than the fact of meaning, but this would be to fall into the effect of the image, the relief effect (trompe l’oeil); it is perceived as three-dimensional but the image is flat, it is in two dimensions; however, the dimension of display is given at the moment of pure perception.

2. It constitutes a sign; it has a specific function. The images are connected, and that confers a symbolic dimension: the analogon becomes a sign. This is an operation of the spectator but it is the cinematographic apparatus that provides it. He says that as much as it resembles the real, it always adds something to it. There is a conceptual element that goes beyond the concrete object. Mitry establishes a distinction between the represented and the representation

3. In the filmic discourse any element refers us to the framework in which the representation is enclosed (separation from reality). The appearance of reality is given beyond the existing concrete. The image is there as a sign because it is the representation of reality; the image dereals reality (neantification). It is the biggest peculiarity of the filmic spectacle, a peculiar and sinister element of the cinema: reality seems so present and at the time so absent (it cannot be touched)

4. One has to speak of a first level of perception (demonstration) and a superior level of meaning. The meaning is given by relating one image to the next. Mitry talks about esthetic and psychology of cinema, not coincidentally.

In the cinematographic spectacle we find levels of perception, narration and poetic meaning. Mitry attributes to the level of the narration the experiments of Kuleshov (1947), who does not value positively. For him it is not the montage that determines the meaning but the power of the story; it is at the level of narrativity that the determining factor is and corresponds to the knowledge of the spectator’s world.

In addition, Mitry deals with the imaginative tradition of cinema from the expressionist Film D’Art and from Eisenstein’s films, arriving at the conclusion that there was excessive concern for esthetic, so that, for him, reality is obscured. He questions, although he is more open than Bazin, with regard to editing, to his former colleagues of the French avant-garde, whom he considers to be estheticists (Gance and Dulac), and his pretension to make cinema a visual symphony, pure rhythm, pure music, pure architecture. For him, the cinematographic discourse is constructed in a rhythm and not for a rhythm; you cannot do without the psychological factors. He questions those movements and Eisenstein’s attempts regarding intellectual or reflexive montage.

Eisenstein had spoken of metric montage, based on the absolute length of the fragments, which are followed according to their measure in a rhythmic, total or harmonic formula that had connections not only at the level of the argument but at the level of the composition itself of an image, what Mitry approves and that makes new meanings emerge. In contrast, the intellectual montage would be the one disapproved by Mitry since it triggers several levels of expression ranging from the most elementary to the most complex and elaborated categories of meanings and implies the introduction of the conceptual element in the image. The most cited example is Kerensky’s metaphorical comparison with a peacock in October (1927); for Mitry this form of montage is questionable because the image has to be connected with a coherence of what is represented.

4.2. Experimental methodologies of avant-garde cinema

4.2.1. Film-poem as abstraction. From French Impressionism to Pure Cinema

Louis Delluc is one of the first film critics, at the same time theoretical, and manages to group around his ideas a group of filmmakers who would be essential in the evolution of French cinematography: Abel Gance, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L’Herbier and Jean Epstein. All of them also theorize about cinema and have an unstable link with the so-called “vanguardias” (term this conflictive).

The filmmaker Abel Gance achieved recognition with J’accuse (1919), which makes it possible to devote two years to his project La Rose du rail, released with the title La roue (1922). It is a film built on the cadence of montage, obsessive and rhythmic, which he himself judges as follows:

I think that in La roue there are images of racing train, anger, passion and hatred for the first time on the screen, happening with an increasing speed and arising from one another in an unpredictable order and rhythm, unleashing visions to which an apocalyptic character was given at the time, and whose use has become as habitual in our cinematographic syntax as the enumeration or the inversion in the literary syntax.

It was not enough. We had to go further in the photography and the transposition of the movement. The filmmaking apparatus, the only immobile one, occupied in capturing all the prodigious and unknown movements that developed around it, had to enter in his turn in the dance. We put it in motion, and I believe to be one of those who took it to the heart of the spectacle of life [...]

A great film must be conceived as a symphony, as a symphony in time and as a symphony in the space (Romaguera and Alsina, 1998, pp. 465-466).

This poetic conception of movement is shared by the whole group and we can also find it in the reflections of Dulac; however, the use of effects and trick photography is not in itself a sufficient condition to link their names to those of the avant-garde, although a broad concept of what this term means includes in its heart, together with the French Impressionism, the German expressionism, the Soviet Constructivism, the Italian Futurism, the Surrealism, etc.

In any case, these are artistic currents that have affected the development of cinematographic expression and that have developed stylistic methodologies far removed from the I.R.M., Institutional Representation Model, conceptualized by Burch (1987); the fact of classifying a whole series of authors and works as avant-garde, at the same time that it “separates” the hegemonic model, “distances” its achievements and maintains the supposed internal coherence of the I.R.M., which, however, does not hesitate to use any type of resources once made them its own and naturalized in their codes:

The avant-garde films were defined not only by their clearly recognizable esthetic, but also by their mode of production, generally handcrafted, financed independently, without connection to studios or industry. In spite of everything, the avant-garde was not at all monolithic. Ian Christie draws a useful distinction between three differentiated movements: 1) the impressionists (Gance, Delluc, Epstein and the first works of Dulac), close to a certain “national art and essay cinema”; 2) the supporters of “pure cinema” (Léger, Dulac at a later time); and 3) the surrealists (Stam, 2001, pp. 73-74).

“Musicality” is a constant search for the impressionists. Influenced by Nordic cinema and also by Griffith, Marcel L’Herbier gets his recognition by El Dorado (1922), where he uses the trick photography with expressive aims, but the contradictory expressionist influence leads him to make Don Juan y Fausto (1922), of very low quality. He recovers later with Feu Mathias Pascal (1925). On the other hand, Dulac, in his impressionist stage, and Delluc, try a naturalist approach to his arguments without abandoning the poetic idea that presides over his concept of cinema. The latter makes two memorable films, Fièvre (1921) and La femme de nulle part (1922), but his unquestionable contribution is the launching of specialized magazines Cinéa and the film clubs, a meeting place for intellectuals and artists. The supporters of a “pure cinema”, who owes nothing to other arts, have an important breeding ground in the existence of these cine-clubs to project a cinema totally alien to the commercial wills and interests.

Jean Epstein collaborates with Delluc in Cinéa and then goes on to direct. His search is fundamentally esthetic-a point shared by all these authors-as can be seen in L’auberge rouge (1922) or Coeur fidèle (1923), but without a doubt his most important achievement is The Fall of the House of Usher, based on Allan Poe (La chute de la maison Usher, 1928) where he uses expressive resources based on trick photography and overprints.

Carlos Tejeda argues that the first abstract experiences are directly connected to Dadaism, founded in 1916 by Tristan Tzara. A Swedish painter, Viking Eggeling, made in 1921 a film that is a continuation of his pictorial work, based on spirals and comb teeth, Symphonie diagonale. This is followed by other “symphonies”, Parallèle and Horizontale . They are animated abstractions whose witness collected by Hans Richter Rythme 21 and Walter Ruttmann in Opus I-IV (1919-1923). The interest of the first films of Ruttmann resided in the representation of the movement and the three-dimensionality of the objects, but unlike the visual exercises of the XIX century, in this case, realized with the technological means of the XX century (Tejeda 2008, p 115). There would also be more “opus” and “rhythms”.

But the French avant-garde cinema runs in other directions, without abandoning the abstraction and the use of objects and forms, but approaching more and more the use of actors and with an effective recognition of the iconic references in the most abstract cases (Turvey 2013). Thus, while the cinema of Man Ray Le retour à la raison (1923) or Fernand Léger Ballet Mécanique (1924), it is directly inspired by the abstract experiences of the Germans. The cinema for Léger is a new means of expression in agreement with his ideas of progress that allow him to achieve results that go beyond the painting itself. The fact of filming objects that usually go unnoticed by the human eye, make them be perceived from another dimension. The painter comes to declare: “once dethroned the pictorial subject, what was stipulated was to destroy the cinematic argument” (Garaudy 1971, p.166).

René Clair, with Entr’Acte (1924), uses actors and works on the cinematographic language through the use of artifices such as overprinting, deformation of the image, idling or accelerated camera. The plot recalls the slapstick and the film takes place as an incessant persecution in which characters related to the intellectual avant-garde of the moment appear and disappear.

An interesting contribution to avant-garde cinema is that of surrealism, creating a dreamlike fusion of illogical and disparate elements. The first work classified as such belongs to Dulac; it is La coquille et le clergyman (1926), according to a text by Antonin Artaud. Later, Dulac works again on the assembly from musical backgrounds in Disque 957, Arabesque and Rythme et variations (1929). But the great revulsive arrives with Un perro andaluz (1928), by Buñuel and Dalí, to culminate with Buñuel’s La edad de oro (1930).

Walter Ruttmann made in 1927 Berlin, die Symphonie einer Grosstadt (Berlin, symphony of a great city), a work that reviews a full day without another storyline that the passage of time in the city as well analyzed by Carlos Tejeda:

The film begins, at dawn, with the planes captured from a train on their arrival in the deserted streets of Berlin. Silence breaks at the dawn of a new day in which, once again, the whole structure of the capital is put into operation: factories, traffic, means of transport, crowds. This fervent agitation that is taking over the city, coincides with the consequent increase in a dizzying pace in the film, gradually fade with the dusk, in which the city returns to the calm. (Tejeda, 2008, p.128)

Unclassifiable, the steps of a documentary film brand new, little linked to the avant-garde, except for the effects used, are intuited strongly. Luis Buñuel and his Land Without Bread (1932) is a good example of the use of documentary techniques at the service of a discursive structure with surrealist touches, an aspect common to the first German and Soviet vanguards. Despite the isolation of the main names of the documentary procedure, from the scientific cinema radically focused on the animals of Jean Painlevé L’hippocampe (1932), to the vindication of the human will Zuyderzee (1933), and the Dutch war chronicles Joris Ivens (Earth of Spain, 1937, or Quatre cents Millions, 1939), there has always been a vein of documentary film that has had irregular responses from the public through the ages.

4.2.2. Film poetry as an analytical model

Expressionism, a term coined by Wilhelm Worringer, is an artistic movement that corresponds to the first decade of the century and manifests itself in painting to later expand to literature and art in general (especially architecture); it is a bet against impressionism and naturalism that appears linked to avant-garde movements but which has a strong philosophical component: the artist must express the world through his art and, as that world is in full decline, sinister emerges, depravity, madness, death (Bai 2015, p. 129).

However, with the arrival of the war, expressionism is diluted and only returns, as a reminder of a past, when peace is established, not without conflicts, especially until the establishment of the Weimar Republic, in which the social problems remain unresolved. To speak, then, of an expressionist cinema is a contradiction:

What leaves its indelible mark on the Expressionist movement is precisely this cross between what separates it from the rest of the avant-garde, making it - let’s say graphically - look back and the fact that this look only erupts with virulence when the Western world is in frank decadence - this circumstance separates sharply the expressionism of perhaps the first historical vanguard, German Romanticism. [...]

It can be said that the primitive fear finds a paradoxical new confirmation in the western uncertainty and the symptom of this unusual encounter is the expressionism. If you look for the specificity of it, there is no doubt that it can only be discovered in this contradiction and it is not a precise conceptualization. A specificity placed at the crossroads. Deeply aggressive in its dissolution of the esthetic universe emerged from the Renaissance, expressionism is, paradoxically, regressive in a modern sense. It raises the fear of the environment, the terror of the ordering space, the need of the inorganic to the category of sign of rupture. And this is exactly what Expressionism adds to the German romantic tradition and that for which it is also separated from the rest of the avant-garde. There is no doubt now, considering these conclusions, that the vague spirit of expressionism, its construction at the crossroads had to be dissolved by the wind when the first world war broke out. The materiality of death, the need for compromise, the retreat or the advance towards a literally decomposed world constituted the most radical and definitive death certificate for the expressionist movement (Sánchez Biosca, 1990, p. 39).

Consequently, it seems opportune, as many authors have argued, to mention certain influences of an expressionist nature manifested in films (especially in architectural aspects) rather than a movement or even a specific mode of representation. To baptize the most representative work, The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (Das Kabinett des Doctor Caligari, Robert Wiene, 1919), as the essence of “caligarismo”, no longer of expressionism, can be a success and a subtle way of avoiding contradiction.

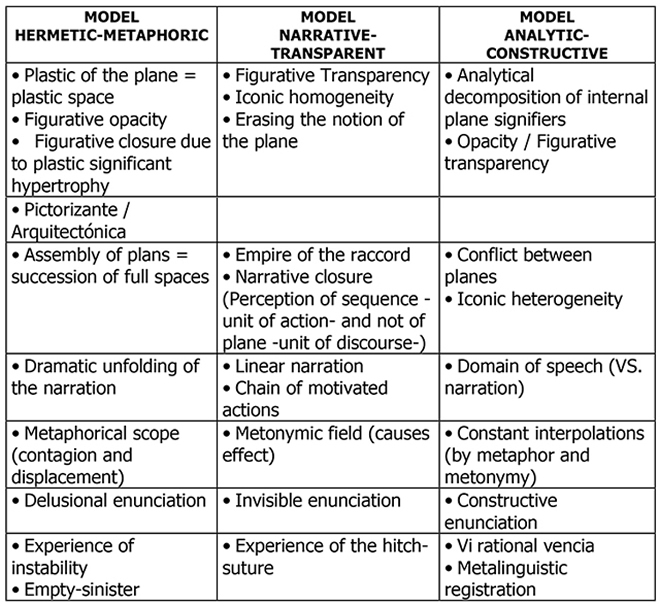

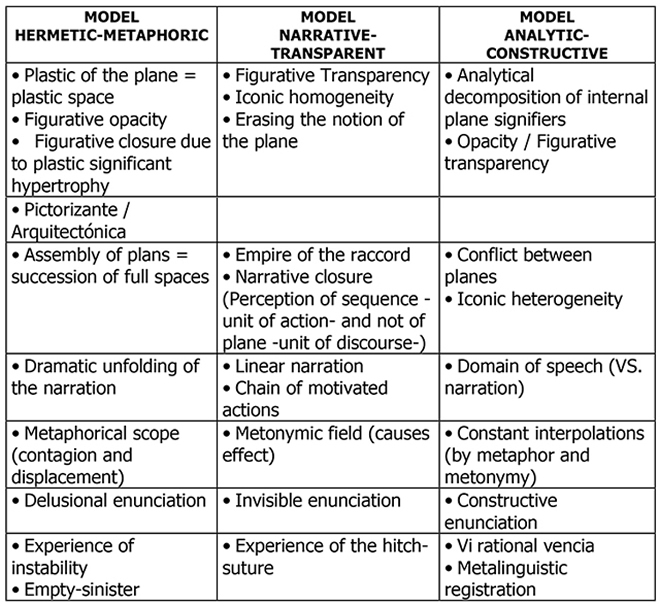

In his important study on cinema during the Weimar Republic, Sánchez-Biosca (1990, pp. 46-57) distinguishes three models of representation and their essential characteristics:

Figure 1. Representation models. These three models are usually always involved, even when their conflicts are organized in pairs. The analytic-constructive model coincides -of course, contradictorily and as a strong model- with the dissolution or marginalization of the metaphorical hermetic.

As it can be argued, the first model gives shelter to a series of generally misnamed expressionist titles, the second corresponds in its general features to the I.R.M. (still in the construction and consolidation phase), and the third one points towards the vanguards, but all they participate in one another and can be tracked in the films. Therefore, it is symptomatic that Carl Mayer, author of the screenplay of Caligari together with Hans Janowitz, is a key man of both “expressionism” and kammerspielfilm and later, in Hollywood, writes the script of Sunrise (1927) by Friedrich Murnau.

With the Expressionist label, in which Nosferatu can hardly fit, other titles of a fantastic, sinister, gloomy nature continue to be made, such as Three lights (Der müde Tod, Fritz Lang, 1921), The Golem (Der Golem, Paul Wegener, 1920), Schatten (Robison, 1922), Das Wachsefigurenkabinett (Paul Leni, 1924).

The kammerspiel (chamber theater) is a return to realism theorized and starred by Carl Mayer. The action is developed recovering the model of the Greek tragedy (rule of the three units), linearity is imposed to avoid the subtitles, there is a great spatial economy, symbolization is promoted through objects, the argument is presided over by the inexorability of destiny. Hintertreppe (Jessner, 1921), Scherben (Lupu-Pick, 1921), Silvester (Lupu-Pick, 1923), The Last (Der letzte Mann, Friedrich Murnau, 1924) would all be written by Mayer.

Most films require the production of their images, that is, shooting. But we find some authors who do without the act of filming for economic reasons when using pre-existing cinematographic documents, or discarded documents. These films are a form of collage, as something that links and that gives rise to a meaning through the link. Very often, you will find in these films a social criticism.

Recall that the English notion of found footage evokes the idea of object found and refers by its simultaneity to the notion of ready-made so appreciated by Marcel Duchamp, although with a manifest inclination towards its development as an assisted object. The artist only made the film Anémic cinéma (1926), which was considered one of the most emblematic in the field of avant-garde experimental cinema. The film consists of a series of alternating sequences of ten optical discs with drawings of off-center discs and nine discs with spiraling word sets. The phrases, in most cases, do not have a specific meaning because they are word sets in which the phonetic character prevails and its meaning is arbitrary. The author defines the work as:

The only one, and I did not even call it a movie, because the idea was the effect and not the film, this being just a means to carry the idea, I did it in 1925, before doing the “rotorelief”, but it was something of the same style, so to speak. That is to say, it was the same sequence of ideas, since it was a spiral for the most part, more than one phrase, a spiral phrase built on the basis of word sets, very funny games. There was a set of words and then a picture up to twelve times. (Marcel Duchamp)

At the beginning of the century, for some filmmakers, they searched the catalogs for scenes already shot in order to create a story. This collage idea did not clash, it was necessary and continued to be appreciated for many years. The shots used in one film could be recycled in another, in order to create effects that caught the attention of the viewer.

For Adrian Brunel it was a common practice to resort to the archived shots in order to alleviate the lack of sequences that could not be shot for one reason or another. Thus, he made the film Crossing the Great Sagrada (1925), composed almost entirely of other travel films. He mixes shots from different backgrounds in order to link or unlink the plot of a story through subtitles and dialogues. In the film a sign announces: “Popular joy in New York”, while in the image we see the relief of the Royal Guard in London; This sequence is followed by another title that announces “They are nothing but savages that dance”. These games of words and images remind us of the calligraphic wit of the dadaists.

On the other hand, in Le Cinema au Service de L’Histoire (1935), Germaine Dulac assembles a series of documents of news that she has patiently collected, in order to give these anonymous films a meaning, a precise mark. The recourse to the found materials seems to establish the opening to other territories and makes the images work that have not been produced by the filmmaker.

4.2.3. Film as dialectical poetry

We are faced with filmmakers who, while carrying out a singular work, theorize about their own conception of cinema and propose models of representation other than I.R.M. based mainly on a radical use of montage methods. The thought of these filmmakers, a bit poets, a little scientists and a little philosophers, is situated between the crossroads of thought and contemporary art.

We opposed, to parallelism and alternating close-ups of America, the contrast of uniting and merging them: the montage-trope (...)

Griffith’s cinema does not know this type of assembly construction. Its close-ups create an atmosphere, design the traits of a character, alternating with the dialogues of the protagonists and the close-ups of the persecutor and the persecuted at a time of great speed. But Griffith always remains at a level of representation and objectivity and almost never tries to juxtapose planes to give form and meaning to the image” (Eisenstein, 1959, p 260).

The montage that Eisenstein theorizes and tries to put into practice through his films is based on the collision of the fragments, for which he starts from the monistic set of the Japanese “in which sound, movement, space and voice are not accompanied (not even in parallel) one to each other, but function as equally important elements” (Eisenstein, 1959, p 39). He is more concerned with the creation of emotions than the representation of reality; his cinema does not seek in any way the “effect of real” or the creation of a habitable space, as the institutional, but the implementation of discursive artifacts with clearly revolutionary contents and capable of involving the viewer in their concepts, in your ideas. From this point of view, it is true that for this filmmaker there is a truth that he intends to transmit, be it the truth of the art or the revolutionary truth (something very different from the perspective of Kuleshov or Dziga Vertov). In this sense Elder, referring to him, defines in his representation model almost hidden connections that would explain the supposed association between mesmerism and electricity in relation to the fact that “at the speed of light, all souls / minds merge, the thought becomes a no sphere, and ideas hang in the ether” (Elder, 2006, p.325 )

The approach to concrete -and representative- texts allows us to see how the I.R.M., in the consolidation phase in the United States, is not in any case the result of a logical evolution from the cinema of the origins. In Europe quite different discursive formulas are produced, among which the Soviet cinema stands out. In essence, for the filmmakers born of the October Revolution, montage is the turning point, the place of construction of the film; if we add that the production system is very different (public funds) and that the protagonist is in the hands of the director, whose name stands out above the “stars” (here generally taken from the town itself, when not directly presented as masses), it is easy to understand that another cinema would have been possible.

Now, there are big differences between directors like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov or Kuleshov, and we cannot speak of a “normative model”; which is, on the other hand, the great advantage of the I.R.M., which, thanks to the teleological vision of history, appropriates many of the experiences of the Soviet filmmakers, naturalizing them, and relegates them to the limbo of the “artistic vanguard” (Nichols 2001, p. 591-592). Among the Soviet Russian filmmakers of the 1920s and early 1930s, before the domination of socialist realism, a clear fusion of interests is evident. Figures such as Rodchenko, Tatlin, Stepanova, Malevich (in his later paintings), Lissitzky, Gan, Popova, Vesnin, the Stenberg Brothers and Mayakovsky were among the many artists who contributed to the creation of a constructivist movement that combined formal innovation with the social.

Dziga Vertov’s cinema is critically positioned against fiction films and goes against the flow of narrative with images that appeal to professional actors, some sets and literary structures carrying values and dominant capitalist ideology. His method of the Cine-ojo, is more a philosophical attitude to create a cinematographic work without authors, without sets or recording studios since all the people that should appear in the film, develop the routine nature of their lives. His glance on reality abandons any creative resource that constitutes a make-up or a mask of the facts. As he argues in his writings published in the book Memoirs of a Bolshevik filmmaker, where he settles in a formula that summarizes and synthesizes the cultural and philosophical climate of the time.

The present film constitutes the assault that the cameras make to the reality and prepares the subject of the creative work on the background of the contradictions of classes and of the daily life. By revealing the origin of the things and the bread, the camera offers each worker the possibility of convincing concretely that it is he, the worker, who makes all things and who, consequently, is the one to whom they belong.

By stripping the frivolous petit-bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie full of fat and returning the food and things to the workers and peasants who have made them, we give millions of workers the chance to see the truth and to question the need to dress and feed the house of parasites.

If this experience goes well, this film, while being independent, will serve as a prologue to the world film Proletarians of all countries, unite. (Dziga Vertov, 1923)

As it is reflected in The sixth part of the world (1926), Dziga Vertov shows in the interior of the Soviet Union, the remote interactions of the most diverse peoples, the crowds, the industries, the cultures, exchanges of all kinds being aesthetically shaped in the time. The author thus flees from the falseness of fiction cinema, tries to show the invisible to the human eye, another point of view of reality without modifying it. Experimenting with the possibilities that the camera allows.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the cinematographic and experimental show of the artistic vanguards we find levels of perception, narration and poetic meaning according to the three levels of reception and interpretation proposed by Mitry and the writings of Dulac in his attempt to define pure avant-garde cinema. The three great methodological variables proposed in this article, group poetic, esthetic and film theory from a perspective of analysis related to the critical theories of the moment and the writings of the artists themselves.

In the first variable “Film poem as abstraction” we provide analysis of works of French Impressionism to pure Cinema and of abstraction. Years with a growing boom in audiovisual experimentation as demonstrated in the experiments of Gance with the making of his film La Roue (1922), is interesting for its lack of editing, the same author talks about the work: “we should go farther from photography and the transposition of movement” “a great film must be conceived as a symphony, as a symphony in time and as a symphony in the space” (Romaguera and Alsina, 1998, pp. 465-466).

Other authors and works analyzed in this variable would be L’Herbier, who gets his recognition by El Dorado (1922), Delluc makes two memorable films, Fièvre (1921) and La femme de nulle part (1922), Epstein, La chute de la maison Usher (1928), Eggeling based on spirals and comb teeth ends Symphonie diagonale (1921), Richter with Rythme 21, Ruttmann with Opus I-IV (1919-1923), Man Ray, Le retour à la raison (1923), Fernand Léger, Ballet Mécanique (1924), Clair, Entr’Acte (1924), Dulac, Disque 957, Arabesque and Rythme et variations (1929) and finally Dziga Vertov, in 1927 Berlin, die Symphonie einer Grosstadt.

The second variable “Film poetry as analytical model” provides a classification of representation proposed by Sánchez-Biosca, based on the hermetic-metaphorical, narrative-transparent and analytical-constructive model. Anémic cinéma (1926) by Duchamp is considered one of the most emblematic works of avant-garde cinema that together with Crossing the Great Sagrada (1925) by Brunel and Le Cinema au Service de L’Histoire (1935) by Dulac, both made from film discards, establishing the cinematic opening towards other territories. And the last and third variable “Film as dialectical poetry”, we analyze a series of works and writings that will be positioned critically in front of fiction films, in accordance with the artistic vanguards of the 1920s.

REFERENCES

1. Bai J (2015). Film Poetry: the Theoretical Institution and Development in the Early Film Theories. International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2015). Advances in Social Science Education and Humanities Research, 23, 128-131.

2. Burch N (1987). El tragaluz del infinito. Contribución a la genealogía del lenguaje cinematográfico. Madrid: Cátedra.

3. Dulac G (1987). The Avant-Garde Cinema. P. Sitney, Adams, (ed), The Avant-Garde Film. New York: Anthology Film Archives.

4. Eisenstein S (1959). Teoría y técnica cinematográficas. Madrid: Rialp.

5. Elder B (2008): Harmony and Dissent: Film and Avant-Garde Art Movements in the early Twentieth Century. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

6. Germaine D (1994). Écrits sur le cinéma (1919-1937). Paris: Éditions de l´Avant-Garde.

7. Kuleshov L (1947). Tratado de la realización cinematográfica, Buenos Aires, Futuro.

8. Mitry J (1973). Esthétique et psychologie du cinéma. I Les structures, Paris: Ed. Universitaires, 163.

9. Mitry J (1973). Esthétique et psychologie du cinéma. II Les formes, Paris: Ed. Universitaires, 163.

10. Nichols B (2001). Documentary film and the modernist avant-garde. Critical Inquiry, 27(4):580-610.

11. Romaguera R, Alsina H, eds (1998). Textos y manifiestos del cine. Madrid: Cátedra.

12. Sánchez-Biosca V (1990). Sombras de Weimar. Contribución a la historia del cine alemán 1918-1933. Madrid: Verdoux.

13. Tejeda, C. (2008). Arte en fotogramas. Cine realizado por artistas. Madrid: Cátedra

14. Turvey, M. (2013). The filming of modern life: European avant-garde film of the 1920s. Cambridge Ma: Mit Press.

15. Vertov D (2011). Memorias de un cineasta bolchevique. Salamanca: Capintán Swing Libros.

16. Wall-Romana C (2013). Cinepoetry: imaginary cinemas in French poetry. Fordham University Press.

AUTHORS

Virginia Villaplana Ruiz

Professor of Analysis of audiovisual discourses and Documentary Cinema at the University of Murcia, Faculty of Communication and Documentation. Specialist in Communication Studies. Researcher at the Communication Institute at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (InCom-UAB). The lines of research he develops focus on the analysis of discourse in communication. She is the author of the books: Infinite Cinema, Softfiction. Policies of visuality in the cinema of Chick Strand, The instant of memory and co-editor of the book Prison of love. Cultural stories about gender violence. It is part of national and European research projects. He is currently developing the SUBTRAMAS research project. Research and co-learning platform on collaborative audiovisual production practices, funded by the Reina Sofía National Museum, Ministry of Education.

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5033-5325

Pedro Ortuño Mengual

Doctor in Fine Arts from the Polytechnic University of Valencia. Professor of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Murcia. He combines his teaching, artistic and research work with the curator of audiovisual exhibitions. He is the director of the academic journal Arte y Políticas de Identidad. Since 2006 the exhibition cycle “Miradas al videoarte” has been curated at the Puertas de Castilla Cultural Center in Murcia. His research questions the role of the media and its relationship with transnational and peripheral identities. He has participated as a researcher and IP in several R & D projects related to identity politics and underground film / video. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9953-5739