Source: Self-made from Christensen and Haas (2005).

http://doi.org.10.15198/seeci.2018.45.15-42

RESEARCH

THE PURE POLITICAL CINEMA: FICTION AS INSPIRATION / REFLECTION OF POLITICAL SPECTACULARIZATION

EL CINE POLÍTICO PURO: LA FICCIÓN COMO INSPIRACIÓN/REFLEJO DE LA ESPECTACULARIZACIÓN POLÍTICA

O CINEMA POLÍTICO PURO: AFICÇÃO COMO INSPIRAÇÃO/REFLEXO DA ESPECTACULARIZAÇÃO POLÍTICA

Yolanda Rodríguez Vidales1

Teacher of the faculty in the Master’s Degree in Political and Business Communication (official Master’s Degree in EHEA), School of Communication, Camilo José Cela University in Madrid. PhD in Information Sciences from the Complutense University of Madrid. Deputy director of the digital newspaper Confilegal.com, dedicated exclusively to the world of Justice. More than 25 years of professional experience in all areas of Communication. In the institutional communication, within the General Council of the Judicial Power, he has worked for more than 8 years as an assistant to the Image of Justice Counsel. She has also worked in radio, press and television and has been the director of the electronic portal of investigative journalism e-defender, between 2003 and 2005.

Graciela Padilla Castillo2

Coordinator of the Degree in Journalism and Contracted Professor PhD in the Faculty of Information Sciences (Universidad Complutense de Madrid). Expert researcher in Theory of Information, Ethics and Deontology and Television Fiction. Doctor with Extraordinary Prize and Degree in Journalism and Audiovisual Communication with End of Degree Award. She has completed her postdoctoral training at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and has traveled as a gender expert to the Benemérita Autónoma University of Puebla (Mexico). Accredited holder ANECA, with a hundred publications, has participated in more than thirty researches and is a member of the UCM Feminist Research Institute.

1Camilo José Cela University. Spain

2Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

The relationship between fiction and politics is palpable in hundreds of film titles, from the birth of cinema to the present day. Democratic spectacularization, or politainment, is vital in political communication, inspired by fiction, and vice versa. As can be seen when producers create social networks accounts for politicians –characters of their series- who make actual but calculated commentary on real politics. Cinema becomes an inspiration and, at the same time, a reflection of reality. Given the type of political films of Christensen and Haas (2005) and specifically, the type of pure political film, we taped five American films, stuck to the environment of their time and clairvoyants of the spectacularization that would come later. They are The Candidate (1972), Power (1986), Wag the dog (1997), Primary Colors (1998) and The idus of March, of five different decades. All deal with the use and handling of appearances and spectacle as a way to gain power or consolidate it. They confirm that politics is conditioned by the media, spectacle and public skepticism.

KEY WORDS: Political fiction, Political cinema, Political Communication, Political Spectacularization, Politainment, Media, Christensen and Haas.

RESUMEN

La relación entre la ficción y la política es palpable en cientos de títulos cinematográficos, desde el nacimiento del cine hasta nuestros días. La espectacularización democrática, o politainment, es vital en la comunicación política, inspirada por la ficción, y viceversa. El cine se convierte en inspiración y, al mismo tiempo, reflejo de la realidad, como queda de manifiesto, por ejemplo, en que las productoras abran cuentas de redes sociales para políticos ficticios –personajes de sus series- que hacen comentarios muy calculados sobre política real. Atendiendo a la tipología de películas políticas de Christensen y Haas (2005) y concretamente, al tipo de film político puro, desgranamos cinco cintas norteamericanas, íntimamente relacionadas con el entorno de su momento y precursoras visionarias de la espectacularización que vendría después a caracterizar a la industria del cine. Son El Candidato (The Candidate, 1972), Power (1986), La cortina de humo (Wag the dog, 1997), Primary Colors (1998) y Los idus de marzo (The idus of March, 2011), de cinco décadas distintas. Todas abordan el uso y manejo de las apariencias y el espectáculo como forma de obtener el poder o consolidarlo en un sentido político y real de la expresión. Confirman que la política está condicionada por los medios de comunicación, el espectáculo y el escepticismo –o carencia de él- del público.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Ficción política, Cine político, Comunicación Política, Espectacularización política, Politainment, Medios de comunicación, Christensen y Haas.

RESUME

A relação entre a ficção e a política é palpável em centos de títulos cinematográficos, desde o nascimento do cinema até os dias de hoje. A espetacularização democrática, o politainment, é vital na comunicação política, inspirada pela ficção e vice-versa. O cinema se converte em inspiração e, ao mesmo tempo, reflexo da realidade. Atendendo a tipologia de filmes políticos de Christensen e Haas (2005,) e concretamente, ao tipo de filme político puro, separamos 5 fitas norte-americanas, relacionadas ao entorno de seus momentos e clarividentes da espetacularização que vinha depois. São: O Candidato (The Candidate, 1972), Power (1986), A Cortina de fumaça (Wag the dog, 1997), Primary Colors (1998) e Os Idus de março, (The Idus of March, 2011), de cinco décadas distintas. Todas abordam o uso e manejo das aparências e o espetáculo como forma de obter o poder ou consolida-lo. Confirmam que a política está condicionada pelos meios de comunicação, o espetáculo e o cepticismo do público.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Ficção política, Cinema político, Comunicação Política, Espetacularização política, Politainment, Meios de comunicação, Christensen e Haas.

Received: 26/09/2017

Accepted: 14/11/2017

Published: 15/03/2018

Correspondence: Yolanda Rodríguez Vidales

yolandahoo@yahoo.es

Graciela Padilla Castillo2

gracielp@ucm.es

1. INTRODUCTION. WHEN THE CINEMA INSPIRES POLITICS. WHEN POLITICS INSPIRES CINEMA

Since the emergence of the film industry, politicians intuited its ability to impose their own vision of things on the world. First, the cinema and later, television, became ideal vehicles to export the American way of life. The changes that political communication has been operating throughout its history have also been shaped by them. The relationship of the Americans with politics has been portrayed in a multitude of movies and television series.

Behind the Hollywood film industry, there is a whole world that transcends mere entertainment. It is the world linked to fame, to money and also to politics and power. The most distracted spectator cannot fail to recognize the high degree of Hollywood alliance with different sectors of political power. It is important to study the representation of politics in the fiction produced in the United States (Hollywood and independents) and its repercussion on real politics. As Gubern (2008) points out, the collaborative relationship between Hollywood and Washington has always existed and this has been reinforced by the attacks on September 11:

Hollywood was always a supporter of continuity in relation to the slogans of the White House, because even when it made progressive films during the Depression, it did them following the guidelines of the Roosevelt New Deal. In 1980, it was able to turn such a mediocre actor as Ronald Reagan into president of the nation. Not only that, but Reagan rescued the title of a successful movie by George Lucas, Star Wars (1977), to baptize a gigantic war-space fantasy that financially knocked down the Soviet Union, which already spent most of its national budget in military expenditures.

This harmony between Washington and Hollywood was reinforced after September 11, 2001, as a result of the trip taken to Hollywood two months later by Karl Rove, President Bush’s top adviser and strategist. He was going to meet with the dome of the entertainment industry and impart the slogans required by the terrorist attacks and their effects on the imagination and consciences of their fellow citizens. By then, the expression axis of evil had been consolidated, a concept that seemed to be taken from a science fiction comic or from a film serial of the thirties. Now, the famous axis had to be stretched a little, so that the capillary and decentralized war promoted by Al Qaeda, a ubiquitous force that ended up acquiring the label of Islam-fascist (Gubern, 2008), would also fit.

It is not surprising that some of the leading Hollywood screenwriters held a secret meeting with members of the Ministry of Defense to analyze possible plots about hypothetical new terrorist attacks:

A few days after attacks on September 11, the international press echoed a meeting between the heads of the US Defense Ministry and numerous screenwriters and filmmakers in Hollywood. Among them, John Milius (the co-screenwriter of Apocalypse Now), Steven E. De Souza (the screenwriter of The Crystal Jungle) and, more surprisingly, Randal Kleiser (the director of the comedy Grease) ... The conclusions of this reflection group they have never been made public, but the press retook the official thesis according to which this meeting was intended to ask Hollywood screenwriters to imagine possible plots of a future terrorist attack and the answers that could be provided (Salmon, 2007, p. 176).

Behind this meeting was Karl Rove, the architect of Scheherazade’s strategy. This term was coined by the professor of the University of Colorado, Ira Chernus: “When politics condemns us to death, we begin to tell stories - stories so fabulous, so captivating, so fascinating that they get the king (or, in this case, the American citizens, who in theory govern our country) forget the capital punishment “(in Salmon, 2011, p.45). Rove was the man who would design the storytelling of war for George W. Bush, as a way to exercise power, transforming the American political life into a succession of evocative stories or emotional stories, many being mere appearances of truth.

Movies and television series can be considered portraits of contemporaneity and politicians know it. They represent intrigues, stories or events of reality that set trends for the future. Their plots can become premonitory of political and social developments, because they perfectly illustrate concepts that have not yet found an empirical correlate in the Social Sciences. The cinema and television series are a good tool for sociological and political analysis. The evaluations and effects that, from the political fiction can be created in the audiences, would allow an approach of these subjects from a fresher and easier perspective for the spectator. In a time of great political upheaval, skepticism and saturation, fiction should be used as a platform to understand politics.

2. OBJECTIVES

The reflection on the relationship between fiction and politics is inescapable to understand the evolution of democratic systems towards total spectacularization of reality. American fiction has a transcendental weight in the global culture, which must be considered to value how the models of action of the politicians have been constructed. Therefore, the analysis of both elements provides clues about the functioning of political communication and its evolution, as fiction has been reflecting. Thus, the main objective of this piece of research is to validate these ideas, through the analysis of cinematographic fiction as an inspiration and reflection, at the same time, of political spectacularization.

3. METHODOLOGY: TYPOLOGY OF CHRISTENSEN AND HAAS

It would be impossible to quote all the times that a president, a presidential candidate or a governor has appeared on the cinema screens, either as a secondary character or as an absolute protagonist, or through fictional stories that choose the character at the moment in which they hold office:

Elections - or, more especially, the moment that precedes them: electoral campaigns - have often been the subject of attention by the film industry, attracted by both the dramatic potential of what, in addition to being a simple procedure for the selection of rulers, implies after all a struggle - not always peaceful or subject to Law - for power; as for the possibility of launching through the film a political message likely to influence future electoral processes or, at least, to conform the viewer / citizen / voter with a moral assessment of politics and politicians (Flores Juberías, 2010, pp 125-126).

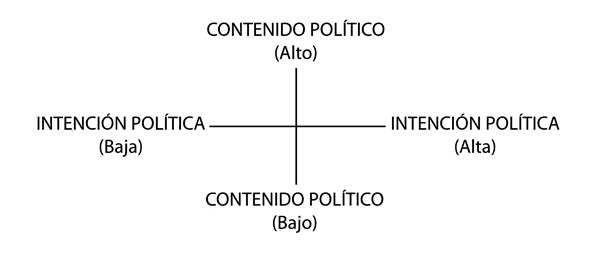

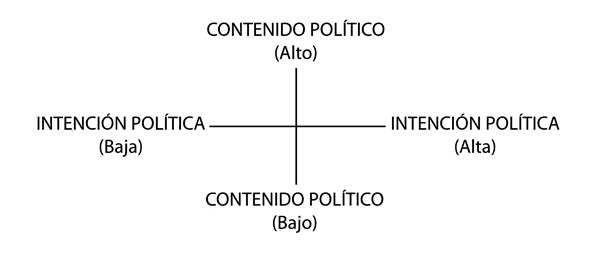

To narrow research and choose the representative films of political cinema, we will follow the typology proposed by Christensen and Haas (2005). They make a typology of political films based on certain criteria, which move away from the problem of whether or not there is a political genre, despite that volume of films around the world of politics. To these authors, there are two dimensions in a film to assess its political level: content and intention. Both dimensions move between two variables: high and low. It allows you to draw an abstract classification through the following diagram:

Figure 1: Diagram of the dimensions of the political level of a movie.

Source: Self-made from Christensen and Haas (2005).

With these parameters, they distinguish four basic types of political films: pure (high content and intention), author (low content and high intention), socially reflective (low content and low intention) and politically reflective (high content and low intention). We will focus exclusively on the pure type, specifically the cinema of elections, characterized by focusing on the political and electoral atmosphere with the communicative intention of influencing the audience and the voters. There would be five very representative films of the last five decades: The Candidate (1972), Power (1986), Wag the dog (1997), Primary Colors (1998) and The ides of March (2011). All deal with the use and management of appearances as a way to obtain power or consolidate it.

4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND STATE OF THE ART

Elections constitute, in a democratic system, the mechanism that best describes the proper functioning of a society. Candidates, parties and communication offices set in motion all their communication potential, in order to obtain the vote of the citizens and thus, obtain the power, by delegation, granted by citizens. Many of the basic strategies of modern political communication take shape during electoral processes. Although the right to vote is only exercised every four years, the electoral periods are getting longer and, even in the current democracies, there is a tendency towards a permanent campaign. The campaign contains the essence of how political communication works on the ground: transcendence in making quick decisions, speeches, the framing of messages, the adaptation of discourse to the media, the preparation of the candidate’s image:

The cinema is, to Nimmo and Combs, a form of political mediation that reveals the strategies and rituals of power. Therefore, the films and products of mass culture contribute decisively to the formation of a political imaginariness through which individuals give meaning to the world that is beyond immediate experience and, therefore, interpret the political process and its actors. Moreover, the collective political identity is also given by mediated representations of history that are offered as a common reference to collective memory. In this type of representations, the cinema also functions as a powerful mediator of the collective imaginariness when it comes to constructing the cultural identity of a community (Trenzado, 2000, p.54).

There is a multitude of movies about politics. Some stand out, for example, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), one of the great works of Frank Capra, where an ordinary man who embodies the values ??of American democracy comes to the Senate and faces the political-financial groups who want to manipulate him; Citizen Kane (1941), which portrays the immense power of the press through the life of billionaire Charles Foster Kane, a character inspired by press mogul William Randolph Hearts, played by the great Orson Wells, who sees how his campaign for governor fails due to a piece of news about an extramarital affair; The Best Man (1964), in which an irreproachable candidate for the American presidency receives furious attacks from the other candidate; The Candidate (1972), key to understanding the process of an electoral race towards the presidency of the United States, explores the dark side of political life and denounces the corrupt effect of a campaign; The Front Page (1974), an acid satire of Billy Wilder on the sensationalist press, the judicial system and the American society of the late 1920s; and (All the Presidents Men (1976) that relates the Watergate case.

In the following decade, in Power (1986), Sydney Lumet performs a critical analysis of political campaigns and advisors, who sell an image, and to whom political ideas matter little. It deals with the power-money binomial, corruption, lies and deceptions invade politics. In the nineties, JFK (1991) speculates on the assassination of the American president; Bob Roberts (1993), on the campaign of a populist; Nixon (1995) recounts the rise and fall of the controversial president; Dave (1993) introduces the romantic genre within the White House; (The American President (1995), which gives rise to the series The West Wing of the White House; Absolute Power (1997) , where its director, Clint Eastwood, shows a corrupt president capable of everything to hide a crime; Wag the Dog, (1997), about the false war created by a film director to cover the sexual scandal of a President; Friendship (1997), where President John Quincy Adams has to deal with slave trade, the abolitionists and a very complicated trial; o Primary Colors (1998), which highlights the dirty work in the electoral campaign.

In the 2000s, 13 days (2000) shows the missile crisis in Cuba in October 1962; Bobby (2006) recreates the assassination of Robert Kennedy during the election campaign; in The Man of the Year (2006), a successful television comedian that satirizes politicians makes the peculiar decision to run for the US presidential election as an independent. Against all odds, Robin Williams will win. And The Challenge: Frost vs. Nixon (2008) or The Ides of March (2011), which analyze the ambition and dreams of greatness of a political advisor. During the campaign, the protagonists will see to what extent one can reach in order to achieve political success.

In the closest years, we can highlight LBJ (2016), with the actor Woody Harrelson playing President Lyndon B. Johnson; Undecided: The Movie (2016), about two young undecided voters and their experiences in the presidential election campaign of Donald Trump; and Our Brand Is Crisis (2015), where actress Sandra Bullock plays a political consultant specializing in crisis, working between the United States and Bolivia.

Likewise, we have reviewed the state of the art with academic research, which has studied political communication and electoral campaigns in film and television fiction. Huerta Floriano (2008) analyzes the ideological activism of Hollywood as a militant opposition to the government theses, in the documentary of denunciation, the political fictions and the reading the military cinema makes of the Iraq War. Rodríguez Vidales (2010) studies the series The West Wing, throughout its seven seasons and 155 chapters, with its fictional and real political situations, through the scheme by RE Hiebert. In 2014, Rodríguez Vidales (2014) also reflects on the relationship between Americans and politics in films and television series; and about the relationships and games of the fictional characters, according to the Transactional Analysis by Eric Berne. And the same author inspects the television series as a platform to understand politics, as portraits of contemporaneity, the intrigues, stories or events of which can lead to trends (Rodríguez Vidales, 2015).

Gelado and Sangro (2016) study Otherness as a pejorative term assigned to non-Western peoples, in Hollywood films, from the end of the 1960s to the end of the 1990s; and reflect the political and ideological ties between the White House and Hollywood. Banegas Flores (2016) delves into the image of Bolivia in its cinema and how the Bolivian space, popular culture and national history are represented on the big screen. Guichot Reina (2017) assimilates political socialization, affectivity and citizenship in the Spanish cinema of the Transition.

We also recommend other excellent academic works, which deal with spectacularization, electoral campaigns, televised debates or politainment, outside fiction: Espizua and Padilla (2017), Jivkova, Requeijo and Padilla (2017), Valbuena and Padilla (2014 ), the analyzes by Valbuena (2010a and 2010b) and Padilla (2010), separately, or the works by Requeijo and Padilla (2011), García Lirios, Carreón, Hernández, Bautista and Méndez (2013), D’Elia (2013), or Piñeiro and Martínez (2013). These readings are of great interest and collect diverse and rich theoretical frameworks for those who wish to retrospectively expand any of the aforementioned channels.

5. DISCUSSION: ANALYSIS OF THE FIVE PURE POLITICAL FILMS

In this section, according to the main objective and the methodology, we break down the five films of a pure political type, in increasing temporal order until today.

5.1. The Candidate (1972): the triumph of politics of the image

Flores Juberías stated: “If there is a film that deserves the paradigmatic qualification of this kind of cinematographic subgenre that is the one devoted to the portrait of the electoral processes, that would undoubtedly be The Candidate “ (2011, p. 41). The plot kicks off the very night when Marvin Lucas, a veteran image consultant, sees in frustration how the candidate he has been working for loses the election badly, and decides to make a radical turn in his career, putting his knowledge and extensive experience at the service of a diametrically different candidate, Bill McKay. His idealism, youth, charisma and ecological and social concerns seem appropriate to differentiate himself from the Republican candidate: a conservative populist veteran who has been representing California for years.

Lucas manages to convince him to accept to go to the Senate elections, letting him know that his chances of prevailing over his veteran opponent, Jarmon, are so remote that he can always say what he thinks without fear of destroying his non-existent options for victory. This, obviously, will change as his chances of winning increase. He will have to give up giving his opinion on abortion, tinge his ecologist message, change his anti-war position and count on the support of his father, a former governor, with whom he has little relation.

After the presentation of his candidacy, where Bill McKay is seen as dynamic, without ready answers and sincere, Lucas realizes that they have the raw material. But something else is needed and he resorts to the advice of a media consultant, who, after analyzing the press conference of McKay’s presentation, proposes to make some changes. In short, he considers that, in order to gain votes, the candidate’s profile and image count more than the program or the party:

ADVISOR: I like him. He’s very crude but I like him. There is a lot of work to be done, but I get the impression that he knows what he wants.

BILL MCKAY: I don’t know.

MARVIN LUCAS: Bill is worried about the control we can exercise ...... with what publicity we will act .... Anyway, those things.

ADVISOR: Well, Luc knows. He has already worked with me and knows that I have investigated about you. The summary is this: I like what he defends. He has guts, if not, I would have rejected him. We’ll get the people together and we’ll get the thing going at once. Thanks, beautiful. You deal with reaching the public. I’ll take care of the cameras. I’ll be back in a week, I’ll show you what I have and check the results.

BILL MCKAY: Yes, but I have the last word.

ADVISOR: How?

BILL MCKAY: That I have the last word.

ADVISOR: If you don’t agree, let’s not talk anymore. The money is yours, friend. It looks good.

BILL MCKAY: We’ll see.

ADVISOR: I’m going to tell you one thing.

BILL MCKAY: Tell me one thing.

ADVISOR: Maybe he wins, boy. People are going to take a look and see a brave man. Then they will take a look at Jarmon and think that he no longer convinces them.

BILL MCKAY: A kind of tournament, huh?

ADVISOR: Forget I told you. I want to teach you one thing. Look. Look closely at this. I think it will impress you. Say? Keep talking. Have you seen that? He acts with a rehearsed posture. How many politicians do you know who look directly at the camera, without a fleeting look? Over-elaborate, huh? And what? It’s what they want. He’s a teacher. He will be the conservative and you will be the independent. For now, you will have to cut your hair and trim your whiskers.

BILL MCKAY: How?

ADVISOR: Well, let’s go there (He shows him several videos of his opponent ). This is twelve years ago, doing the number of the man of the town. This guy knows what he wants. The guy has a hook. There is nothing new in the world, except perhaps you.

MARVIN LUCAS: It’s about placing yourself in situations that are natural.

They decide that it is on McKay’s image, his youth and independence, on which his election campaign should be based. Senator Jarmon represents continuity, he is the hard father and the man of the people exhibiting his experience as a determining fact for reelection. One could say that the Candidate is a pure political film, as Christensen and Haas classify it. The film, based on electoral experiences of the team, anticipated the career of some real politician. And, in this sense, they point out that:

Robert Redford was the star, the producer and the driving force of The Candidate (1972), the first film and the best that he tackled, in the decade of the 1970s, political campaigns and a classic example of a film with a high content and political intentionality. Although The Candidate mysteriously projects the career of California Governor Edmund G. - “Jerry” - Brown, writer Jeremy Larner and director Michael Ritchie based the script on their experiences in the 1970 campaign of John Tunney, a Kennedian senator from California. Several events in the film were inspired by Tunney’s campaign, and the senator was allowed to oversee the script and agree that “it would not be a blow to his person,” according to Ritchie (Christensen and Haas, 2005, p. 146).

The ultimate goal of this film is to denounce the spectacular methods and manipulation of the electorate, through the image used in a modern electoral campaign, where television occupies a central place. It is also appreciated how campaign volunteers take street people, elderly people from residences to take them to vote. This declaration of intentions, together with the low budget, provides the film with an almost documentary tone. Ian Scott (2000, p.78) points out that this realistic style was achieved by shooting Redford many hours among street people, giving the feeling of plausibility and realism:

Ritchie imitated this realistic style by rolling hours with Redford shaking hands with ordinary Californians -a key scene that took place in front of the Long Beach shipyards- having his McKay character make impromptu performances at various rallies and rolling heads and shots. shoulders of the public giving their unconditional support. The director of photography of the film, Victor Kemper, used as many public events as he could to immerse Redford in naturally enthusiastic crowds (Scott, 2000, p.78).

The description of the campaign through the men who work for the political parties during an electoral process reflects the reality of that time well. Part of the members of the production team, including screenwriter Jeremy Larner, had already worked on election campaigns:

Michael Ritchie, director of The Candidate (1972), and his screen - the writer Jeremy Larner, for example, worked on political campaigns in the 1960s - Larner wrote speeches for the presidential candidate of Eugene McCarthy in 1968 (Scott, 2000, p 66).

The film reflects the enormous evolution of political marketing in American public life, with the emergence of television and its expansion to all areas of society. In the 1970s, this medium prevailed over others as a source of information for the population. Philippe J. Maarek explains that this transformation is based on collaboration between the political class and the image consultants:

The 1968 US presidential election, however, provided televised political communication with the opportunity to discover the full range of possibilities by systematically exploiting those offered by the use of the foreground, thanks to the connivance between Nixon and a young 27-year-old television producer, Roger Ailes. This one, in fact, managed to convince Nixon to be as natural as possible, and that he let himself be filmed as often as possible in the foreground ... in short, recipes were applied that still today encourage the popularity of the figures, whatever they may be, on television (Maarek, 2009, pp. 39-40).

In short, in The Candidate, politics is reduced to marketing operations, which treat the politician as a product to sell to the electorate through advertising techniques. Something that the protagonist realizes. You can see how all the initial freshness of the candidate gradually changes. His speech will be continually modified and polished by the communication team, with a view to creating a new political profile, without too much shrillness that is easily sold to a large electoral spectrum. He will be aware of this when listening to a television journalist, editorializing in his newsletter about the evolution of the campaign he has been doing:

JOURNALIST: The search for votes made by a political candidate must be somewhat higher, with moral implications for the kind of people we are and who we would like to be. But lately in this country, candidates have a tendency to mix the two things. Announcing themselves as if they were a brand of deodorant, even with advertising phrases that discredit both the candidate and the voter. However, in the Californian elections, young Bill McKay has acted differently. He manifestly rejected the political machinery that gave his father position and fame and carried out a refreshing campaign in which sincerity prevailed. But now, with only a month to go, McKay’s methods have visibly changed. His first statements are losing strength and his specific programs dissolve into vague generalities. Advertising has been imposed on him as a normal system of persuasion. Voters are asked to choose McKay as they could choose a detergent. Nothing comes into moral considerations. Once again it seems that integrity cannot be maintained throughout the entire campaign.

From here, his behavior changes. He adapts to what his advisors propose and becomes a professional politician, achieving his goal: to win. All moral principles gradually vanish for the sake of obtaining office, turned into an end in itself and not in the medium of social transformation. It is seen when he goes to a rally in a factory. McKay begins his speech with a joke in the manner of professional politicians, which is what he has become. Then, he uses the arguments of his program on unemployment, health and education and raises the enthusiasm of the audience. McKay controls pauses to perfection and plays with the emotions of the spectators. The middle planes of his advisor, Marvin Lucas, smiling and nodding, confirm the transformation of McKay into a new star of politics:

BILL MCKAY: I happened to be here ... No, now seriously. It is very nice to speak to an audience of workers because I can congratulate you for having all a job. You all work, right? Good, good, good. How many of you are unemployed? The number of unemployed in this state reaches eight percent. Do you realize? The largest, richest and most powerful country on Earth cannot give a job to its entire labor force. It cannot attend to all his patients. It cannot feed its entire hungry people. Provide education to those who have the right to receive it. Well, I affirm that there must be a better system. To me this is what these elections mean because it is no longer possible to turn our back on the fundamental needs of the people. And I do not think that, at this point, they can be distracted by confronting the young with the old, the white with the black, the poor with the less poor ... I think the time has come for the American people to realize that we must be united. We sink or we are saved, but together and I sincerely believe that this is how it should be. And that is to test our courage, our compassion, our faith in ourselves and also in our homeland. No candidate can appear before you and assure that he has all the answers. That is to say, none of them: Crocker Jarmon affirms that he has them. Is that right? The only thing I can say is: Here I am. And that’s what I tell you tonight: Here I am ready to give everything I have! Let’s make a new beginning!

That entire road to the electoral victory is a personal defeat. To achieve this, he has had to renounce ethical principles that the character considered essential in his way of understanding politics and society. In short, McKay has ended up resembling his father: a professional politician who must assume the defense of interests of pressure groups - as seen in the campaign rally organized by the trade unionists - who have mobilized their people to get him elected. The end is devastating and demonstrates the loneliness of the candidate, after the maelstrom of the campaign:

MARVIN LUCAS: We have about sixty seconds before they find out we’re here. What did you want to tell me, senator?

BILL MCKAY: I don’t know.

MARVIN LUCAS: Good. I have to go out there. I already told you that they would come right away.

BILL MCKAY: What are we going to do now? I’m already a senator, now what?

5.2. Power (Power, 1986): the power of marketing techniques applied to politics

Sidney Lumet carries out an analysis of the political campaigns, and those responsible for them, authentic publicists of sale: the political consultants. Entrepreneurs who teach how to sell an image by working, side by side, with politicians who care almost nothing about political ideas. And, as its main protagonist, the political consultant, Peter St. John, says: “ Political plans are not important, what matters is winning “. As the film critic of El País, Octavi Martí (1986) claimed:

Power is a film made against the current, an updated version and from the other side, of the mythical Juan Nadie by Frank Capra. If in 1941 the protagonist was a baseball player who was manipulated to launch him as a candidate for the presidency, in Power the hero is one of those manipulators, an image consultant. Then, this film is about substituting the malice of the ex-American gigolo, Richard Gere for the ingenuous honesty of Gary Cooper. The millionaires are amused or interested in getting involved in politics, but they need experts to tell them how to behave at every moment to convince the voters and appear more honest, intelligent and competent than their rivals. Richard Gere provides advice, provides tricks, investigates everywhere and always offers himself to the best bidder so that he has a chance to win. Once in the seat, that is the senator or deputy’s problem with his conscience.

Always interested in the subject of corruption and power, Lumet approaches the work of an image consultant, capable of producing attractive politicians for the general public and hiding their dirty clothes in passing. Its protagonist is all adrenaline, he spends his time listening to jazz and playing with the drumsticks the song “Sing, sing, sing” by Benny Goodman, while he travels by plane from one place to another to serve his clients scattered around the world:

Director Sidney Lumet and writer David Himmelstein ignore the fact that politicians have always manipulated voters, blaming the new technologies and the credulity of the public almost entirely for the sadness of the nation. All the politicians of the film are unsuspecting, except for the governor (Michael Learned). Power deepens, in an instructive way, the techniques used by media consultants, although the film grossly exaggerates their influence (Christensen and Haas, 2005, pp. 184-185).

The film emphasizes the importance of the image of the candidate (pre-digested and pre-canned) and the manipulation of each decision, however minimal and insignificant, as well as the influence of the media on the electoral process. It is realistic about the power-money binomial, as its poster reads: “More seductive than sex, more addictive than drugs, more precious than gold, and a man can get it for you ... for a price. Power. Nothing comes close.” It also talks about the corruption, pressures, lies and disappointments that invade politics and addresses some important communication techniques such as opposition research or the preparation of interviews and debate:

It is not, therefore, just to sell an image, or just to make it out of nothing and invent an ideal, but to accurately draw, with the help of surveys, technology, money and imagination, the profile of the electorate, of hidden dreams of which the politician will be a concentrate in which everything is included (Martí, 1986).

After the abandonment of his friend, Sam Hastings, to revalidate his office in the Senate, Pete interviews the person who wants to succeed him, Jerome Cade, warning him that the campaign to reach the Senate will cost him 10 or 12 million dollars:

PETER ST. JONES: What is your weak point?

JEROME CADE: The one about my candidacy, you say. Probably, not having any political experience. Although, personally, I consider it an advantage.

PETE ST. JOHN: It’s not serious. And you have done some work in the Administration. In addition, we can enroll you in a seminar at Kennedy School and have them publish a document in “The Times”, maybe. Money is not a problem. Have I understood?.

JEROME CADE: No.

PETE ST. JOHN: Let’s see, I would start with ... You have not done any survey yet but we would say you’re 16 or 18 points below. And just by getting the nomination, that would go up.

JEROME CADE: I deduce then that you will work with me, Mr. St. John.

He soon discovers that Jerome Cade, his client, works for a group of very influential people able to investigate him, control his phone, his mail, etc. Later, he finds out that this pressure group has bribed his friend to leave the office of senator, which they want to occupy. After this, he visits the lobby behind Cane, where he confirms his suspicions. Lobbyist Arnold Billing, played by Denzel Washington, who represents oil companies in the Middle East, openly threatens him. This will cause the protagonist to abandon that candidate and decide to support the weakest candidate: a young and idealist university professor, represented by his former mentor, adviser Wifred Buckley. He tells him what he has to do to succeed. He shows that he still has principles and that in a campaign there can also be something human:

PETER ST. JONES: Look, I’m sorry if I offended you but you have nothing to do.

WILFRED BUCKLEY: How dare you come in here and come with these ...?

PHILIPS AARONS: No, leave him. I want him to continue

PETER ST. JONES: He’s a smart man. He’s a teacher. He has nothing to do. This is one of the sad realities we never say in front of the one who pays us. Listen, instead of going back to your class to teach history, why not launch tonight and make history. You have nothing to lose. Why don’t you go to the stand, stand up, and say exactly what you think? What you think, maybe even what you feel. Not what the polls say, not what Wilfred says, or what I say.

WILFRED BUCKLEY: (Angry). Are you implying that I don’t know how to deal with my client?

PETER ST. JONES: Wilfred, I’m not referring to you, you’re the best of us all, but it doesn’t matter who runs the show. It’s always a show.

5.3. Wag the Dog (1997): political reality as fiction

The relationship of cinema with politics is evident, especially in the decade of the 90s of the last century, when William Jefferson Clinton becomes President of the United States and several Hollywood productions approach the political sphere with him as a cinematographic referent. Wag the Dog can be among those images, which confuse the public, by correctly mixing reality and fiction at a time very opportune for Clinton’s interests. He could have benefited from a calculated media confusion caused after the premiere of the film. This is explained by García Fernández (1998, p.93):

Wag the Dog (1997), a film that tells us about the sex scandal that is about to ruin the reelection of the president of the United States, and how his advisor weaves a whole network of fiction -a war with Albania- to divert the attention of the Americans and, especially, of the media. For this, the consultant uses the work of a Hollywood producer who will be able to set up an audiovisual montage that will reach the American people through digitized images, background songs that speak of the “American dream”, heroes born out of nowhere - which are always manufactured as necessary- that revolutionize the patriotic spirit of a nation. It is a story about events that happen overnight, is production ahead of events or does it take advantage of them? It is a country that mobilizes before a prefabricated image, before rumors that are refused but raise suspicion. Those aspiring to power look for any small detail that can provide the push they need to sit on the highest place. Society does not seem to care much about things; it does not understand that they are ripping it off, moreover, they participate fully in the production of a fiction that keeps all the hints of reality. Although it is clearly incredible, Albania can have a nuclear briefcase, and danger is on the border with Canada, where a terrorist command threatens the strength of the most powerful country on the planet. Is it crazy? Who can have this come to mind?

The screenwriters of the film put on stage a communication consultant, Conrad Brean. A spin doctor that the President uses in difficult moments, whose job is to change the focus of the media story through successive smokescreens. These are understood as fictitious facts that are given real status with the simple fact of properly pronouncing and recreating them in the media, especially on television, which is the one that marks the media agenda. The first step is to provoke a pseudo-event that gives time to redirect political discourse. He does not hesitate to hire a Hollywood producer, Stanley Moss, to bring plausibility to a false war against Albania. Washington resorts to Hollywood, a perfect ally for its ability to create spectacle, fiction. The conversation between Brean and Motss is a grotesque display of the risks one runs in a society of spectacle and entertainment:

STANLEY MOTSS: Why Albania?

CONRAD BREAN: Why not?

STANLEY MOTSS: At some point they’ll have to know.

CONRAD BREAN: Who?

STANLEY MOTSS: The public.

CONRAD BREAN: Do they have to know? Let’s see. Who killed Kennedy? I read the first draft of the Warren report. It said he was killed by a drunk driver. The Gulf War. What did you see every day? The smart bomb falling through a chimney. The truth? I was there when we shot that attack. We shot it in a studio in Falls Church, Virginia. A model on a 1/10 scale of the building.

STANLEY MOTSS: Is that true?

CONRAD BREAN: And how do we know? Do you follow me?

STANLEY MOTSS: Okay. And what do you want me to do?

CONRAD BREAN: Produce it.

STANLEY MOTSS: Do you want me to produce your war?

CONRAD BREAN: It’s not a war. It’s a show. We need a theme, a song, some images. It’s a show. It’s like the Oscars. That’s why we appeal to you.

STANLEY MOTSS: I’ve never won an Oscar.

CONRAD BREAN: It’s a shame, but you’ve produced the Oscars.

STANLEY MOTSS: Actually, yes.

After accepting the commission to produce the war, Brean and Motss begin to write an argument that gives meaning to the war story, which will materialize in the media in the coming days. The trigger for the conflict will be the terrorist danger that threatens the American way of life. This type of plot hook is a safe value because it directly concerns the emotional aspect and, therefore, makes it possible to avoid, at least immediately, the rational issues. Fear is a recurrent argument, used by the American political powers, to justify their strategies, especially in the international arena. The film becomes a kind of making of the virtual war they are going to shoot. It proposes the simulation of a virtual international conflict to divert the attention of an audience avid of entertainment of the reality: a sexual scandal of the President.

In that same sense, Ramonet points out how the Monicagate exemplifies the way in which the media amplifies an event, with the aim of distracting the audience from the essentials. The war against Saddam Hussein and its geopolitical implications remained in a discreet background thanks to the media and judicial scandal about President Clinton’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky. The film by Barry Levinson undoubtedly contributed to this entire media show:

The disproportion between the supposed event and the din of the media reached such an extreme that it led people to suspect that Clinton had mounted all the pieces of the crisis against Baghdad to divert the evil power of the media to Iraq and Saddam Hussein. In spite of everything, after five days of delusions and media hysteria, Clinton obtained 57 per cent of favorable opinions among the Americans. The same Americans who were nevertheless persuaded that he had had sex with Monica Lewinsky. We see that, in the era of virtual information, only a real war can save us from informational harassment. An era in which the two parameters exert a decisive influence on information: media mimicry and hyper-emotion (Ramonet, 1998, p.18).

When, in the film, Senator Neal, the opposition candidate, appears on television, in a news program, announcing that the CIA has confirmed that the conflict with Albania has ended and the American troops are withdrawing from the Canadian border and the outside, presidential advisers must act again. This piece of news acts against the interests of the President and his team, because it places, once again, the presidential sexual scandal on the media agenda. It is a constant struggle to set an agenda appropriate to the electoral interests of each of the candidates. Motss, on the other hand, is reluctant to let his film be finished:

SENATOR NEAL: It’s been a great week, Richard. I cannot remember another President who has had the flu, a war and who has been accused of sexual abuse by a teenager all in a seven-day interval. All this, of course, a few days before re-election. We just received news from CIA sources confirming the cessation of hostilities...

CONRAD BREAN: The CIA.

WINIFRED: They let us go too easily.

CONRAD BREAN: The war is over. It’s over. I’ve seen it on television.

WINIFRED: I have to sell my house.

STANLEY MOTSS: The war is not over. I’ve seen it on TV. That’s why I was hired. The war does not end until I say it’s over. It is my movie. It’s not the CIA movie.

To continue with the farce, the conflict must be given a new dramatic turn. Motss and his team create a hero who has not heard that the war is over and continues the fight on his own. With this story, they intend to create a decoy that engages the interest of the media and the voters with a double function: to decrease the interest in the presidential sexual scandal and, at the same time, to elaborate a patriotic discourse that electorally favors the Government. If the scandal was a safe sale for the media; a war, based on fear of the other, is even more so. It will be the president himself who, in a speech, announces the rescue operation.

When Motss, Ames and Brean return to the White House operations office, the producer affirms that what they are doing is pure politics: that is, the continuous creation of media falsehoods is what politics has become:

PRESIDENT: American friends, I thank God and I am sure that we all thank the Almighty for the power to achieve peace. The nuclear terrorist threat has been silenced. We are in contact with the Albanian Prime Minister, who assures me, and this government trusts his words, that his country does not wish us any harm. A member has been abandoned after what were the enemy lines. I can only say that I know the members of the 303 Group have met to comfort you. I tell the parents of the lost man that we will spare no effort to find this brave man and bring him back home. I just received this photograph of Schumann held by a dissident group of Albanian terrorists. I do not know how many of you know the Morse code but, could you bring the camera closer? You will see that his sweatshirt is threadbare. And that it has come unstitched in some places. Those ripples form stripes and dots ... and all that makes up a message in Morse code. That message says, “Courage, Mom.” He got the message out.

Fiction marks the political agenda. It functions as a determinant account of a current situation that, apparently and paradoxically, is to come and establishes the political agenda by prioritizing the issues to be addressed: the president’s sexual relationship and attacks on other countries as a distraction of the audience. Wag the Dog becomes a prediction about how the media work and who controls them. It does it from the beginning, with its disturbing start-up puzzle: “Why does the dog wag its tail? Because the dog is smarter than the tail. If the tail was more clever, then the tail would wag the dog.”

Its impact on political reality at the time of its production, with a calculated mixture of historical reality and fiction, makes it almost impossible for the viewer to distinguish one from the other. Let us recall that this movie premiered while the Lewinsky scandal broke out in Washington and the national press was subject to criticism from within and from outside. The film entails the acceptance and total comprehension of the politics composed in the media scene in terms of show business. Its protagonist, Conrad Brean, does not stop repeating, every time they accuse him of the fact that the conflict cannot be real: “I’ve seen it on television”. A social situation is produced where the image is not a substitute for reality but becomes reality itself, independently of having existed or not. The appearance of truth goes through reality itself. As the expert in political communication Luis Arroyo (2012, pp. 214-215) assures:

When Wag the Dog was released, Washington commentators pointed out the curious coincidences of the film’s argument with the events that shook Clinton legislature: his revealed relations with the intern Lewinsky, the long persecution, with a proposed motion of censorship, on the part of the republicans, the silences and, finally, the confessions of the president. And, in the middle of the story, military interventions, not made of papier-mâché, but real, in Sudan and Afghanistan, on August 20, 1998. Clinton’s rates did not improve with those military operations, probably because there was no previous attack to the United States, nor an enemy identified by the population. However, the president’s approval did not go down despite having had to testify a few days before. Clinton endured all that scandal with rates that were on the scale of sixty-something percent, an extraordinarily high figure.

Another curiosity of this film is that it predicted, with enough precision, the reasons to be used for the second Gulf War (March 20, 2003 to December 18, 2011), justified by two arguments made by the Bush administration and already used in the film as an alibi for the military intervention in Albania: the existence of mass destruction weapons - in the film, a suitcase bomb located in Canada - and the connections of the country with fundamentalist terrorist groups.

In 2016, Pep Prieto included Wag the Dog among the 50 essential titles on political communication and he explains its success this way: “The most suggestive of the film are the parallels between the construction of a political argument and the creation of an audiovisual fiction. It is not that the two languages ??are similar: they are the same. The difference, according to the thesis of Levinson and Mamet, is that politics phagocytes everything it touches and, in its unexpected ending, kills art when it is best for it “(Prieto, 2016, p.100). Likewise, he argues that it is still topical because: “It survives as a committed film model capable of making those it portrays turn red, and it is also one of the few films that has formally treated the relationship, permanent and not necessarily beneficial, between cinema and politics “(Prieto, 2016, p.100).

5.4. Primary Colors (Mike Nichols, 1998), any resemblance to reality, sometimes, is not coincidence

It is a film that adapts the novel by Joe Klein, which narrated the first presidential campaign of Bill Clinton, through Senator Jack Stanton. However, the screenplay by Elaine May is quite far from the political details of the book and focuses on the sex scandals of the senator, played masterfully by John Travolta. He will have to face an accusation that jeopardizes his career towards the White House. A case that recalled Clinton’s slip-up a few years before:

It provides a sharp and penetrating vision of the ins and outs of that sub-world -in the world of politics- which is the electoral campaigns, especially the American ones; it provides - although in a disparate measure - flashes of comedy, dramatic tension and deeply moving moments; and, above all, it puts on the table more than half a dozen important questions about which any spectator with whom the condition of citizen and voter also concur cannot evade reflection. In this sense - and for an instant, abstracted from its cinematographic merits – Primary Colors provides an excellent starting point for any debate about politics and politicians, democracy and parties, participation and criticism, the press and public opinion, or privacy and the right to information, which does not want to remain in the limbo of pure abstract reflection. What are the ethical limits that should not be crossed in a political confrontation? How far do citizens have the right to know about the privacy of their politicians? What role should the press play in an election campaign? What can there be of theatrical, and what should there be of authenticity, in an electoral campaign? Where is the line that separates the reasonable strategy of adapting the message to the public to whom it is addressed from the most blushing of lies? How much can the past matter, and how much can the present, in the message of a candidate? (Flores Juberías, 2011, pp. 93-94).

This movie leaves no one indifferent, for its undeniable similarity in the plot and the characters with the race that led Clinton to the White House. It affects the similarities between the profile and the history of its protagonists, the Stanton (Jack and Susan) and the Clintons (Bill and Hillary) and, therefore, with the most characteristic characters of their immediate surroundings:

The above-mentioned parallels are more than evident in regard to both the figures of Jack Stanton and Bill Clinton and those of his wife Susan and Hillary. The former, in addition to a southern origin and a physique that reminds without effort of the one of the “man of Hope”, shows along the film a whole rosary of gestures and behaviors easily identifiable with those most clearly defining the personality of Clinton, ranging from his fondness for donuts and fried chicken -Clinton’s fondness for junk food was legendary- to his irrepressible weakness for flashy women, to others less shocking but equally revealing, such as his ease of speech, his enormous capacity for persuasion, his taste for direct communication and even for physical contact - see in detail the scene from the beginning of the film in which Stanton shakes hands with those waiting to listen to him - and his facility to connect with his interlocutor - again: note the priceless scene in Krispy Kreme. For her part, the character Susan Stanton faithfully reproduces that hardness of character, that unwavering determination, that dryness in dealing with others and that irrepressible desire to succeed that many of those who know her - and many more, among those who do not - have been attributing to Hillary Clinton (Flores Juberías, 2011, pp. 95-96).

And there are not only those similarities with the two protagonists of the film, as well as the skeptical spin doctor of the team - an Anglo-Saxon term that the novel popularizes - Richard Jemmons. A typical southerner, redneck, with racist tics and a declared macho chasing “Winonas” (Ryder) in every woman who crosses his path. It is a role of great strength, played by actor Billy Bob Thornton, as an experienced cynic with brilliant ideas, albeit a pale reflection, in presence and character, of his real-life counterpart: James Carville, creator of the effective slogan “It’s the economy, stupid!” The coordinator of the campaign is Henry Burton, a young idealist, intelligent, hardworking black, the grandson of a leader of civil rights, who, at first, was attracted by the magnetism of the Staton couple, given his inexperience in election campaigns.

HENRY BURTON: Susan, ma’am. Staton, I don’t know. I’m not sure. I had never collaborated in a presidential campaign

SUSAN STATON: So what? Us neither. But that’s how the Henry story is made, with the newbies.

Later, Henry has to decide whether or not to support Jack Staton, after seeing how he presses Picker, revealing what they have found out about him to leave the campaign. Thus he clears his way. At that moment, Jack pulls his best seduction to try to convince him. He talks about the sacrifices and the price that comes with power:

HENRY BURTON: Governor, I’m retiring from the campaign.

JACK STANTON: Well, I don’t accept your resignation.

HENRY BURTON: Hey, I want you to know that I’m not comfortable with all this anymore.

JACK STANTON: In what?

HENRY BURTON: In this, in this office.

JACK STANTON: I’ve talked to Richard and he’s back on board. I put him in charge, Campaign director. You will already be in the office. I will also bring Daisy back, if she accepts.

HENRY BURTON: I don’t do it for that, governor.

JACK STANTON: Then, why?

HENRY BURTON: By Libby. You flunked Libby’s exam.

JACK STANTON: Yes, but now I just approved it. And what do you say? What grade did I get, Henry? High or low?

HENRY BURTON: If she had not died ...

JACK STANTON: If she had not died, I would have leaked the report and I would have regretted it, but you know what? It would have been a mistake not to filter it. But what I’ve done I’ve done for Libby, but it has not been fair. If Picker had not retired, he would have won and sunk. And with him, the game. It was only a matter of time.

HENRY BURTON: And how, and who has pushed him to the edge of the abyss.

JACK STANTON: All these are assumptions, subtleties, Henry. It’s like saying, how many angels fit on a pinhead? This is stronger. Will you tell me that you have just discovered that you lack guts? I know you well, we’ve spent a lot of time together. This is so, Henry. It is the price paid for being a leader. Do you think Abraham Lincoln was not a bitch before being President? He had to tell Chinese tales with his poor country peasant smile. And he did it to be able to one day have the opportunity to stand before the nation and appeal to the best angels of our nature. And that’s where the lies end. And that’s what it’s about, to get the best in the best way. You know, like me, that there are a lot of people playing this and that they don’t think like that. They are willing to sell their soul, to crawl through sewers, to lie to people, to take advantage of their worst fears for nothing. Only for the prize.

HENRY BURTON: I don’t care, I’m sorry. I don’t compare the players. I don’t like the game. I want to work encouraging people to register to vote.

JACK STANTON: And when they’re all registered, who will they vote for? Deep down, Henry, who can do better than me? Think about it. Is there anyone out there able to win the elections? Who can do more for people than me? Who cares about the ones I care about?

HENRY BURTON: Oh fuck - seeing the reporters behind the fence - That damn driver. I was sure.

JACK STANTON: It’s okay. We’ll go together to talk to them. Come on. Don’t shake your head, Henry. We have worked hard to get here. And it’s right there, within our reach. We can do incredible things. We can change this entire country. I’m going to win this, and when we win we’ll make history ... Look me in the face and tell me that’s not going to happen. Look me in the eye, Henry, tell me you don’t want to participate. Fuck, Fuck, Come on, Henry ... Do you want me to get on my knees? I can’t do it without you. Now don’t leave me. Say yes! (Burton’s gaze is inquisitorial).

Primary Colors addresses the techniques of electoral marketing, especially some aspects related to persuasion. It narrates the conflict between ideology and cynicism, the superficiality of images, the rhetoric of campaigns and the manipulation of the media. Loyalty in politics is also seen through the character of Libby Holden (Katie Bates). She is able to become the “dirt-digger” of the cause of her beloved leader, at the moment when the scandals begin to uncover. When the Statons decide that they should investigate the opposition, candidate Freddy Picker, Libby helps them, thinking that they will do the right thing with the information that she discovers. However, it is a job that does not please her and she is somewhat reluctant:

LIBBY HOLDEN: I take the dust off, I protect you. I don’t annihilate the adversary.

JACK STANTON: And what the hell difference is there?

LIBBY HOLDEN: All the difference in the world. All the moral difference in the world. I’m not interested in sinking poor Freddy Picker.

SUSAN STATON: What if he’s bad? If he’s a scoundrel?

LIBBY HOLDEN: It will be known.

JACK STANTON: But when? Let’s say he wins the nomination to the candidacy and then you know. Look at this -and he throws a paper airplane at her- It’s the result of the analysis that Dr. Boregar gave me.

LIBBY HOLDEN: Congratulations. Surely this will help.

JACK STANTON: Well, no. Libby, Honey, you know that. It doesn’t matter that my blood doesn’t match the baby Loretta is expecting. And it doesn’t matter that I can’t be the father. The only thing that would matter is if I were the father. Because guilt is what matters. I have to put up with it and let Picker get a special pass because you were Picker’s voter in the 70s.

LIBBY HOLDEN: I mean, injustice for everyone? It’s a reasoning of imbeciles.

SUSAN STATON: Okay, but this one is not. Picker could be guilty of fraud or tax evasion. If he used his influence to help his brother-in-law, he doesn’t deserve to be president. It could be a worm. You have to forget who you thought he was. You have to find out who he really is.

To know the persuasive methods, nothing like seeing in action the amoral and Machiavellian Howard Ferguson, played by the famous television actor Paul Guilfoyle (CSI Las Vegas). He does not hesitate to sign a paper with incomprehensible terms for a friend of Jack Stanton, practically illiterate, whose daughter may be pregnant by him. Likewise, he resorts to handing over a false sample of urine, from the uncle of the governor, so as not to harm the candidate.

Even being fiction, the film focuses on real political figures and eyewitnesses. Mike Nichols makes a crude and undisguised portrait of one of the most famous presidents of the end of the century, albeit referring to the beginning of his career at the White House. A leader and a candidate, be it Jack Stanton or Bill Clinton, capable of conquering the masses with his charisma and personality. The film deals with the subject of appearances. It tells us how the candidate is able to adapt to any place and circumstance to get the vote: endless meetings in which he falsifies the stories to convince potential voters, betrayals of his wife and friends, blackmail ...

5.5 The Ides of March (2011): the lies of the political system

The Ides of March is a nefarious date in ancient history: the day that Julius Caesar was stabbed in the back. Although the event occurred many centuries ago - 44 years before Christ - that date has acquired a superstitious aura, as on Friday 13th. “Beware of the Ides of March,” said Shakespeare’s soothsayer to Julius Caesar, and those words have been heard many times since then. The film of the same name offers a rather realistic vision of the world of politics, where the protagonist, Stephen Meyers (played by Ryan Gosling), is an idealist and brilliant communicator, who supports the candidacy of Governor Mike Morris (George Clooney) -a rising and charismatic politician, whom he admires and blindly trusts. He is an idealist, at the beginning:

STEPHEN MEYERS: There’s a big difference between Paul - the campaign manager - and me. Paul only believes in victory, so he will do or say anything to win.

GOVERNOR MORRIS: But you don’t.

STEPHEN MEYERS: I’ll do or say whatever if I believe in it. But I must believe in the cause.

GOVERNOR MORRIS: You’ll be a lousy adviser when you leave this job.

STEPHEN MEYERS: Well, I won’t leave this job while you’re still there, sir.

GOVERNOR MORRIS: As much, you have eight years left. Then you’ll end up in a nice consultancy of Farragut North, earning 750,000 a year and eating in the best restaurants, offering the services of senators to Arab princes.

STEPHEN MEYERS: Maybe I’ll offer former presidents.

GOVERNOR MORRIS: Well, I better win.

As the plot progresses, we see how the protagonist discovers that in politics there is no good faith and the most important thing: that loyalty can turn indistinctly into treason. Thus, after being aware of the logic of power, Meyers will take advantage of the candidate’s mistake: he has made a campaign grantee pregnant that died after aborting, to blackmail him, manage to save the campaign and catapult to the top of power:

GOVERNOR MORRIS: What do you want?

STEPHEN MEYERS: You throw Paul, today. I have prepared a meeting with Thomson, you’ll promise him the vice president, you’ll get 356 delegates, you’ll get North Carolina and you’ll get to the Presidency. And you’ll do well the things that many people have done wrong. The things we both believe in.

GOVERNOR MORRIS: I don’t believe in extortion, nor in being tied to you for the next eight years.

STEPHEN MEYERS: Four years, don’t want to run so much.

The critic Carlos Fernández Castro (2012) pointed out in the film blog, bandejadeplata :

The characters played by Ryan Gosling, Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Paul Giamatti (directors of political campaigns) make manipulation their way of life, believe they use candidates as a child does with his toys, charge a fortune for something that does not yield any benefit to the rest of society, expose the prostituted role of the media in the world of information.

The Ides of March questions what is more important: the political race, the victory or the truth. It is a harsh criticism of the corruption of the American electoral system, which can be applied to any similar context. It is based on the premise that the political world is almost irremediably contaminated and that those who claim to represent our interests, at times, only seek to obtain power, under the excuse that only when they manage to win the elections they will be able to fulfill their impressive campaign promises. Here we must ask ourselves where the truth, transparency, the values ??of life and the human quality that is needed to be a good political leader are. The critic of El País, Carlos Boyero, argued the following in his article “Miseries of Politics” (2012):

Clooney, a fervent Democrat who has campaigned publicly for Obama, who never cut short his critical opinions about the devastating Bush administration, narrates in this disturbing and lucid film the dirty maneuvers throughout an electoral campaign that aspires to the Presidency of the United States, what is hidden behind appearances that pretend to be immaculate, the manipulation of public opinion, the sophisticated theater mounted by the image advisers, the contradiction between the supposedly luminous discourse of the one who aspires to absolute power by promising the common good and the darkness and the traps of his personal conduct, the ins and outs and the lies as a rule of conduct in the name of pragmatism to achieve victory.

Beau Willimon, the screenwriter and author of the play on which the film is based, is inspired by his behind-the-scenes experience of some Democratic campaigns such as those by Howard Dean, of whom he was his spokesman, or Hillary Clinton herself. It is easy to recognize some features of Dean in the character played by George Clooney, such as his opposition to war or being too anti-religious for the US average, as he states in a debate during the Democratic primary in Ohio, before his adversary, Senator Pullman.

In short, The Ides of March is a fierce criticism and without prudishness to the lies of the political system and especially, the political animal itself, which struggles between idealism and ethics. It reflects how candidates talk about what they do not represent, how everything is an advertising image in which the media play a fundamental role. According to the screenwriter Beau Willimon, to the newspaper El Mundo: ‘”Ideals do not matter. It matters what you are willing to do to win.” And he added:

People who are engaged in politics find themselves again and again before ethical decisions that can destroy idealism. You are between the sword and the wall. You have gotten into the campaign because you care about the issues, you have solutions to fix them and you want them to be applied. At the same time, you present yourself against someone who defends issues and solutions completely at odds with yours. And to achieve your ideals, you must first win. The two parties want to win so hard that you resort to tactics that contradict your idealism. For idealism to triumph you often have to do very cynical things (Willimon, 2012).

In 2016, Pep Prieto also included this title among the 50 essentials on political communication: “It talks about how a professional of political communication can end up betraying his values ??when his methods become as much or more obscure than those he believes he fights. We attended, then, the previous hours of a Democratic convention with an almost documentary vocation to show what we do not see in the process of building a candidate” (Prieto, 2016, p.156).

6. CONCLUSIONS

This piece of research started from the hypothesis that the relationship between fiction and politics is palpable in hundreds of film titles, from the birth of cinema to our days. The democratic spectacularization, or politainment, is vital in political communication, inspired by fiction, and vice versa. Cinema becomes an inspiration and, at the same time, a reflection of reality.

American film fiction has a transcendental weight in global culture, which must be considered in order to assess how the models of action of politicians have been constructed. The analysis of both elements provides clues about the functioning of political communication and its evolution, as fiction has been reflecting. To narrow research and choose the films representative of political cinema, we followed the typology of Christensen and Haas (2005). Specifically, in the type they called pure political film. With this, we have observed, analyzed and broken down five American tapes, stuck to their moment and clairvoyants of the spectacularization that would come later: The Candidate (1972), Power (1986), Wag the dog (1997), Primary Colors (1998) and The ides of March (2011), of five different decades. All deal with the use and management of appearances and spectacle as a way to obtain power or consolidate it. They confirm that politics is conditioned by the media, the spectacle and the skepticism of the public.

Fiction reflects reality but, at the same time, modifies it and helps modeling the world. In the strictly political sphere, the reviewed films show the important role of the electoral team in the design of the candidate and the strategies that he must follow in order to win the elections. In addition, this type of film contributes to the mythification of the work carried out by political advisers, whose work is essential in any campaign. Politicians need to surround themselves with a team of advisers and this need is directly proportional to the degree of spectacularization of politics. Politics is conditioned by the media and the political strategists, the so-called spin doctors. These are able to justify almost any action of the politician on duty to which they sell their services. In addition, these films contribute to consolidate that detachment and skepticism of the public in relation to politics.

7. REFERENCES

1. Arroyo, L. (2012). El poder político en escena. Historia, estrategias y liturgias de la comunicación política. Barcelona: RBA Libros.

2. Banegas Flores, C. (2017). Territorios y espacios de identidad en el cine boliviano, en Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 5, 89-108. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15304/ricd.2.5.3311

3. Christensen, T. & Haas P. J. (2005). Projecting Politics. Political Messages in American Films. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

4. D’Elia, N. S. (2013). La mujer en la política: ¿igualdad o diferencia? Una invitación a la reflexión, en Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 32, 31-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2013.32.31-40

5. Espizua, I. & Padilla, G. (2017). La imagen y el estilo de la mujer política española como elementos básicos de su comunicación. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 41, 61-83. doi:https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.42.62-84.

6. Fernández Castro, C. (2012). Los Idus de Marzo (The Ides of March) (2011). Recuperado de http://www.bandejadeplata.com/criticas-de-cine/los-idus-de-marzo-the-ides-of-march-2011/.

7. Flores Juberías, C. (2011). Seis ensayos sobre cine y política. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia.. Recuperado de: http://www.uv.es/cinedret/CarlosFlores.pdf

8. García, C.; Carreón, J.; Hernández, J.; Bautista, M. & Méndez, A. (2013). La cobertura de la prensa en torno a la inseguridad migratoria durante elecciones presidenciales, en Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 30, 57-73. doi:https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2013.30.57-73

9. García Fernández, E. C. (1998). Cine e Historia. Las imágenes de la historia reciente. Madrid: Arco Libros.

10. Gelado Marcos, R. & Sangro Colón, P. (2016). Hollywood and the representation of the Otherness. A historical analysis of the role played by the American cinema in spotting enemies to vilify. Index Comunicación, 6 (1), 11-25.

11. Gubern, R. (2007). Hollywood se aleja de Bush, en El País, 14 de noviembre de 2007. Recuperado de http://elpais.com/diario/2007/11/14/opinion/1194994812_850215.html.

12. Guichot Reina, V. (2017). Socialización política, afectividad y ciudadanía: la cultura política democrática en el cine de la Transición española. Historia y memoria de la educación, 5, 283-322. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/hme.5.2017.16704

13. Huerta Floriano, M. A. (2008). Cine y política de oposición en la producción estadounidense tras el 11-S. Comunicación y Sociedad, 21(1), 81-102.

14. Jivkova Semova, D.; Requeijo Rey, P. & Padilla Castillo, G. (2017). Usos y tendencias de Twitter en la campaña a Elecciones Generales españolas del 20D de 2015: hashtags que fueron trending topic. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 824-837. doi:https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.05

15. Maarek, P. J. (2009). Marketing político y comunicación. Claves para una buena información política. Barcelona: Paidós Comunicación.

16. Martí, O. (1986). A contracorriente, en El País, viernes 24 de octubre. Recuperado de http://elpais.com/diario/1986/10/24/cultura/530492413_850215.html.

17. Otero, T. (2013). Presencia, uso e influencia de los diputados del Parlamento de Galicia en Twitter. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 32, 106-126. doi:https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2013.32.106-126

18. Padilla Castillo, G. (2010). Los conflictos entre Ética, Moral y Política en la Comunicación Institucional y Periodística de las series de televisión Sí, Ministro y Sí, Primer Ministro. CIC: Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 15, 165-185.

19. Prieto, P. (2016). Poder Absoluto. Las 50 películas esenciales sobre política. Barcelona: Editorial OUC.

20. Ramonet, I. (1998). La tiranía de la comunicación. Madrid: Debate.

21. Requeijo, P. & Padilla, G. (2011). Los discursos de Barack Obama: un ejemplo de espectacularización teledemocrática, en S. Berrocal Gonzalo, (Coord.). Periodismo político: nuevos retos, nuevas prácticas: actas de las comunicaciones presentadas en el XVII Congreso Internacional de la SEP, 5 y 6 de mayo de 2011 (pp. 391-412). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

22. Rodríguez Vidales, Y. (2010). El ala oeste de la Casa Blanca (The West Wing): un tratado de Comunicación Política Institucional. CIC: Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 15, 85-121.

23. Rodríguez Vidales, Y. (2014). La ficción inspira la forma de hacer política, en Revista de análisis transaccional y psicología humanista, 71, 269-286.

24. Rodríguez Vidales, Y. (2015). Política y poder en las series de televisión. Opción: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, 4, 775-796.

25. Salmon, C. (2007). Storytelling, la máquina de fabricar historias y formatear las mentes. Barcelona: Península.

26. Salmon, C. (2011). La estrategia de Sherezade. Apostillas a Storytelling. Barcelona: Península.