Source: Self-made

http://doi.org.10.15198/seeci.2018.45.87-101

RESEARCH

CONCEPTS TO UNDERSTAND ORGANIZATIONAL INNOVATION

CONCEPTOS PARA ENTENDER LA INNOVACIÓN ORGANIZACIONAL

CONCEITOS PARA ENTENDER A INOVAÇÃO ORGANIZACIONAL

Alberto Navarro Alvarado2

Higher Technological Institute of Puerto Vallarta. México.

Rosario Cota Yáñez1

University Administrative Center of Economic Sciences. México.

Cynthia Dinorah González Moreno3

Higher Technological Institute of Puerto Vallarta. México.

ABSTRACT

This paper exposes four aspects that must be considered in the study of organizational structure of the modern organization: the firm as a socio-economic unit, functionality, innovation and competitiveness. This is to say: re-organize it under real efficiency criteria, not priorizing un-productive executive cadres over mid-cadres needed in order to develop effective activity and a viable expansion Project, not only on paper but in practice too. An organization designe for the global benefit of the company and its associates, able to react and to make long-term plans, resulting in a solid and reliable economic institution able to produce profits for longer periods of time. The thematic is taken from a dynamic point of view, integrating these four elements in a theoretical construct that provides solid basis of organizational structure theory that promotes the firm performance in aspects such as competitiveness and innovation. At this point, emerges a very interesting debate, about cause-effect interaction among competitiveness and innovation, inscribing this theoretical issue as one of the most important contributions from this investigation on a field of study that based most of its principles on complementary suppositions, exogenous variables and circumstantial relativities to explain just one phenomenon: the organization.

KEYWORDS: Organizational design, Innovation, Competitiveness, Organic structure, Efficiency

RESUMEN

El presente documento expone cuatro aspectos sustanciales que deben ser considerados en el estudio de la estructura orgánica en las empresas modernas, siendo éstos, la organización, su funcionalidad, la innovación y la competitividad. Es decir: su organización bajo criterios de eficacia reales que no primen cuadros ejecutivos improductivos sobre cuadros medios necesarios para que la empresa desarrolle actividad efectiva y un modelo de expansión viable, no solo sobre el papel sino también en la práctica. Una organización destinada al beneficio global de la empresa y de los socios de esta, con capacidad de reacción y de planificación a largo plazo con el fin de presentar resultados verdaderamente sólidos y resultar en un pilar económico sólido y fiable capaz de generar beneficios durante periodos prolongados de tiempo. Se presenta el tema desde un enfoque dinámico de tales elementos, integrándolos a un constructo teórico que permita establecer sobre bases sólidas una teoría de la estructura organizacional como agente promotor de la empresa, a partir de la innovación y la competitividad. Justo en este apartado, surge un debate muy interesante sobre la causa y efecto de la interacción entre competencia e innovación, inscribiendo este componente teórico como una de las contribuciones más relevantes de esta investigación sobre un campo de estudio que se basa en una serie de supuestos complementarios, variables exógenas y relatividades circunstanciales para explicar un solo fenómeno: la organización.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Diseño organizacional, Innovación, Competitividad, Estructura orgánica, Eficiencia

RESUME

O presente documento expõe quatro aspectos substanciais que devem ser considerados no estudo da estrutura orgânica nas empresas modernas, sendo: a organização, sua funcionalidade, a inovação e a competitividade. O tema se apresenta dede um enfoque dinâmico de tais elementos, integrando-os a um construto teórico que permita estabelecer sobre bases solidas uma teoria da estrutura organizacional como agente promotor da empresa, a partir da inovação e a competitividade. Justo nesse tema surge um debate muito interessante sobre a causa e efeito da interação entre concorrência e inovação, escrevendo este componente teórico como uma das contribuições mais relevantes desta investigação sobre o campo de estudo que se baseia em uma serie de supostos complementários, variáveis exógenas e relatividades circunstanciais para explicar somente um fenômeno: a organização.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Desenho organizacional, Inovação, Competitividade, Estrutura orgânica, Eficiência.

Received: 14/11/2017

Accepted: 10/01/2018

Published: 15/03/2018

Correspondence: Alberto Navarro Alvarado

alberto.navarro@tecvallarta.edu.mx

Rosario Cota Yáñez

macotaya@gmail.com

Cynthia Dinorah González Moreno

cynthia.gonzalez@tecvallarta.edu.mx

1. INTRODUCTION

The study of organizations has been limited to a systematic understanding of organizational operability, and not necessarily in the usefulness and application of such knowledge, since much of organizational theory focuses on explaining social phenomena and not on generating consistent and universal results (Weiss, 2000; Bate, et al., 2000). Any organizational study can be broken down into three constituent parts, design, functionality and performance. However, the theoretical contribution is at a point of discussion in which any subsequent application to the theoretical generation may be outdated or simply be inapplicable to any organization under relativistic argumentation (Romme, 2003).

And it is, precisely, an epistemological and, in some cases, briefly semantic position based on isolated studies, under relatively stable conditions and based on assumptions that can only be empirically tested to the extent that the same conditions are generated, which culminates in normative and rarely generalizable results for an organization as a theoretical entity.

The concentration of methodological and systematic contributions on the study of the organization rarely come to be consistent because they are situational, relative but, above all, heterogeneous (Bethel and Porter, 1998; Arie, et al., 1999). In this paper, we start from the main assumption that organizations share a functional univocity, which lies within the organizational design, since it is precisely the one that determines the organization as an economic entity, but also as a social one. The set of these two elements, and only as a whole, can define the organization, but it is necessary to establish the foundations of a consistent, universal theory and, more than anything else, focused on functionality.

This document is structured into three main parts. The first section briefly sets out four substantial theoretical elements to generate a larger-scale construct, these being the organization, organizational design, innovation and competitiveness. A second part integrates what is described in the first section, seeking to reach a council that determines two important aspects of organization, definition and functionality. Finally, a third part presents the conclusions and recommendations of this theoretical approach on organizational design.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. The organization and the company

By priority definition, it should start from the conception of the organization to be able to establish the organic design as a situation that exists in any company in an immanent way and not as an isolated phenomenon, the last repercussions of which generate substantial impacts on performance; It can only be analyzed on success cases, so it is assumed that it coexists in a competitive environment, such that, by extension, it must offer the right conditions for innovation (Swanson, 1994).

Such conditions are understood as context and act as phenomena not directly controlled by the organization and are of vital importance to achieve business success or failure (Láscaris, 2002). In a broad sense, organization differs from its context, although there is an inherent relationship with it, which is typified into three large groups of variables, namely social, economic and political; a situation that makes it quite complicated to establish a concrete concept of the organization, that is, even with the various definitions that the versatility and multidimensionality of the organizations admit, its concept can be referred to as a set of legal units, the sole purpose of which is to generate variations in the finances; or, similar conceptions can be referred to in the fields of psychology, sociology, economics, and even political science (Davis and Marquis, 2005).

Thus, so as to define the organization, it is necessary to present a broad concept, but it must be established in two parts, these being economic and social. This is due, to a large extent, to the fact that research on the subject has had predominantly humanistic nuances (Mintzberg, 1980, Baigh, 1994, Bate, et al., 2000), and yet it adds strong economic precepts in its practical application (Romme, 2003, Davis and Marquis, 2005). This way, it can be asserted that, in the context of modern markets, the traditional concept - that is, that of “company” - does not fully cover the conditions and functions in which global markets are structured, which categorically define the objective functionality of the economic units that constitute them (as a system). This way, it has been the intention of the business entities the one that has become a generic concept about the very action of individuals in collectivity in search of common objectives, namely the organization, which in the general consensus is approved as an accurate definition (Collins English Dictionary, 2009).

However, when trying to define the organization scientifically, under the rigorous processes that distinguish the analytical method from science, the end of the perspective always seems to be heterogeneity and structural variability (Bethel and Porter, 1998; Arie, et al., 1999; Walker, et al., 2002).

In a semantic sense, the company must imply economic connotations in its definition, while the organization will incorporate social notions that are, by extension, quite complex (Bate, et al., 2000). However, in concrete terms, the organization cannot be split up into its disciplinary components, not even for its study, since the basic principle of integration serves as a restriction. The dynamic interactions of the organization, both of the environment and those that occur within itself, are inalienable, codependent and, necessarily, simultaneous.

It is not, then, the definition (or theorization, if you prefer) of the organization what concerns, and not that it diminishes importance, but as a dynamic agent, its conception rests on the relationships it establishes, as well as the form in which such relationships are established, no longer taking into account with whom they are established; in such a way that the organization has a situational context and an environment of influence.

The business theory only describes the efficiency interactions among organizations but does not explain their why. Thus, studies of the environment (Porter, 1980, Barney, 1991) and of organizational capacities (Peteraf, 1993, Teece, et al., 1997) are only approaches to the dynamics of markets, that is, a systemic-economic approach.

This systemic-economic approach establishes the interactions between economic units, but not the organizational design relations, so it can be assumed that it takes for granted that there is an internal efficiency relationship, since, otherwise, the organization would not exist. The following section addresses the relationship of internal efficiency of the organization, which is based on its design.

2.2. The organizational design

At the end of the seventies of the last century, in the boom in the study of organizations, the work of Mintzberg (1979) laid the foundations for their study, clearly completing the holistic vision that was already perceived in the exhaustivetreaty of Simon and Hall (1958) , although in a rudimentary way, since it was contextualized through group interactions in what can be established as three stages of change: psychological, behavioral and cognitive processes. Until that moment, the organic structure was perceived implicitly in the organization through the individual interactions of its members, which gives the studies of that time totally social nuances.

Through the integration of functional, divisional and integral aspects, Mintzberg (1980) sets out a taxonomy in five basic models, namely the simple, bureaucratic, professionalized bureaucratic, divisionalized and adhocracy structure. However, it admits the combination of all of them and highlights adhocracy as the best possible structure for organizations, which is characterized by its flexibility and adaptability to changes. In any of its structures, the author denotes the existence of categories of work, ranging from strategic to routine operations.

The foregoing shows that organizational structuring is only a part of organic design. The real importance lies in the relational structuring, since along with the achievement of a good organizational design it is expected that the company acquires certain flexibility in the admission of new knowledge (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

Precisely, the flow of information, in the understanding of cognitive elements, is an element of high relevance in organizational design; however, it rests in the way tasks and activities are distributed, so an important disambiguation that has been omitted in most of the current treaties is important here. The organizational design is not a process, or a continuous action, since its purpose is the achievement of functional efficiency under the prevailing conditions for the organization, in such a way that the environment becomes a relative application of those factors that affect organizational operability, ie those elements that are related to variables of an economic nature. Omitting this part incurs a perception error.

Mintzberg’s model of five (1980) clearly sets out a series of aspects to be considered in the organizational structure, such as structure, coordination, design parameters and contingency factors; however, it does not explain the relations among them in a concrete way. Although the approach of Dean et al. (1992), which dogmatically establishes two differentiations to interpret the organizational structure, through subordination or empowerment, makes clear the relevance of the means of control in this aspect. Now, if the organization depends on control, then the schemes for organizational design should be oriented to them, although the theory of the organization clearly emphasizes that there are only three types of control: exogenous, endogenous and social (Ouchi, 1979 ) .

Perhaps because of the relevance of organizational research in social and humanistic aspects, social control seems to be the best documented. Being characterized by the result of interactions among collaborators of any organization, culture and environment, as well as their management as control tools, they are placed in the social continuity of the organization, that is, development (Bate, et al. , 2000).

It is denoted that the relational complexity between culture and organizational design has forced a separate study, where social aspects are alienated from the functional and operative ones, even recognizing the high degree of interrelation that they keep. Such differentiation occurs in two ways, one from the perspective of processes (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) and the other from the focus of social-cultural interaction (Baligh, 1994). In any case, the organizational culture is the result of social interactions within any business entity.

Then, organizational design is the integration of the structure, functions, tasks, activities and social interactions that take place in the organization, considering the external variations of the environment, to guarantee efficiency and, therefore, the achievement of the objectives, through effective means of control, which offer integrated or institutionalized knowledge as a product. However, if all organizations share this condition of design, then, if they are in the same environment, they should seek efficiency, this appealing, naturally, to the economic conception of the organization, that is, the company. This situation is addressed in the next section.

2.3. Competitiveness

One of the most discussed aspects in the last decades has been the ability of organizations to establish dynamic relationships, under uncontrolled conditions, in such a way that they can be beneficial at a global level, which, in such case, are defined as relations of competition.

In the previous sections, two very important concepts for the study of business administration were established. The first one was the organization, as a dual economic and social agent; while the other was the organizational design, understood as the cluster of formal processes that are reflected in the functional, operational and procedural structuring of the organizations.

This section deals with a topic that, although it seems somewhat separate from the consequence of this document, should be studied due to the relationship it has with the concepts already discussed.

Competitiveness can only be placed within the theoretical framework of organizational study under two main approaches. The first of these postulates competitiveness as a condition of the environment (Porter, 1980, Powell, 1992, Peteraf, 1993, Mata, et al., 1993, Rindova and Fombrum, 1999), where a host of factors, generally not controlled by the participating agents, add up to a whole that may be favorable to some of them. Meanwhile, the second denotes certain capabilities that organizations have to generate attractive and beneficial positions in the market in which they compete (Jhonston and Vitale, 1988, Barney and Hansen, 1994, Oliver, 1997, Stabell and Fieldstad, 1998). In any case, competitiveness prefigures as the business system developed by organizations with their environment, lato sensu, in such a way that competitors and other elements associated with organizations are involved.

Given the strategic nuances that the concept acquires in the study of organizations, it is clear that the generation and effective use of knowledge is the basis of competitive business schemes (Láscaris, 2002), since the company must be able to use its resources to gain advantage over its competitors. This situation, precisely, is the priority of competitiveness, since, in fact, it only exists in the business community, that is, a given environment, with particular characteristics.

This way, it has been stipulated that competitiveness in organizations must be their broadest strategic goal (Porter, 1980), which is complicated when situational constraints are more pronounced only in some organizations and, even so, the notion of competitive advantage continues to exist (Barney, 1991). Despite the inconsistencies that occur in heterogeneous environments, competitiveness in organizational study is understood from the point of view of performance, where the achievement of extraordinary returns may well serve as the indicator of its existence, although its nature or nature is not known. (Powell, 2001).

Could this mean that competitiveness exists in a casual or spurious manner? Not at all, however, it is interesting to make clear that competitive advantage depends to a large extent on specific situations for its existence and on relative conditions for its achievement.

And it is that such specific situations can be found within the organization, its value chain, the environment, or any condition that involves the organization, that is, there is no predetermined condition to generate competitive advantage, but, rather, a use of the conditions to get the best out of them. Likewise, the position that competitive advantage confers as favorable will depend on the actions carried out by the competitors and, even, the organizations associated with the production or distribution process.

For the purposes of this study, it is necessary to remember that competitive advantage has strategic aspects which the organization can influence, although there are others which it does not. This way, generating sufficient organizational conditions to take advantage of a relative (non-competitive) advantage is the main opportunity for organizational design, since the real strategy lies in being able to sustain this advantage (Barney, 1991).

2.4. Innovation

Innovation in organizations becomes quite complex when approached from the organizational perspective, since it occurs at various levels of the organization, as well as outside it, where the main factor for its existence is the need for adaptability of the organizational system to respond to changes in the environment, so the best definition for innovation will be the one that refers to the implementation of ideas and processes within the organization (Evan and Black, 1967).

According to Láscaris (2002), for innovation to occur, it takes more than the presence of knowledge or the capacity itself to generate potential innovation, it requires joint work of competitiveness, strategy and adaptability. In addition, it is noteworthy that the strategic aspects surrounding innovation as a controllable condition on the part of organizations differentiate it from the concept of competitiveness, since innovation does not necessarily require interaction with other organizations or their environment.

Evan and Black (1967) clearly stated that innovation can only occur through the discovery of an idea, or the development of an idea, which, when implemented successfully, can be considered an innovation. The notion of implementation is recovered as a social function proper to the organizational structure, in which the favorable benefits or actions for the achievement of the proposed objectives are correctly presented, which results from good organizational structure, normally associated with size, although currently, it is more appropriate to refer to an efficient organic structure.

Although not necessarily from a technological aspect, innovation lies in the way information flows within the organization. The constant change of the environment and the need to make the organizational structure more flexible to guarantee its survival generates forced situations of innovation in the aspects related to management and application of information (Swanson, 1994). By adding this information application, we can talk about organizational learning as an integrating process of the perceptions, processes and conditions of innovation, since success, or occurrence of innovation implies the application or management of organizational capacities (Danneels, 2002) .

In this tenor, therefore, organizationally, there are three conditions that favor the development of innovation. The first one refers to the impact of innovation internally, that is, the changes that it implies, such as costs, reconstitutions, among others; a second condition is the organizational structure, which involves aspects such as the level of professionalization and integration, since it depends on the development or inhibition of new ideas that, in the end, will become innovations. Finally, there are the attributes of organizational relationships, which may well be referred to as the flow of information, formalization in processes, high degree of communication, among others, since better integration of innovations depends on them (Evan and Black , 1967)

3. DISCUSSION

The integration of the four concepts presented in the previous section, namely organization, organizational design, competitiveness and innovation, provides a solid basis for the structuring of a dynamic theory that can create generalizations applicable to any organization. It will start by defining the organization according to what is presented in this document.

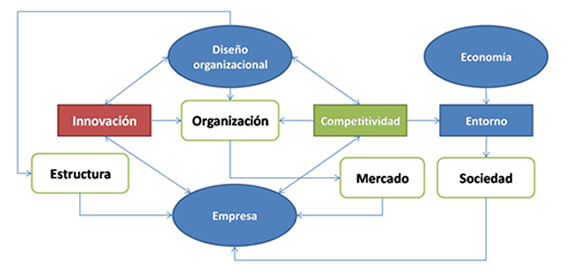

Figure 1 shows the dynamic relationship of the organizational design. This way, the organization is perceived as a dual entity, composed of an economic and a social infrastructure. The economic part of the organization serves the concept of company and responds to aspects of action within the organization, namely the operational and functional, the two aspects being represented by actions and systems. On the other hand, the social infrastructure is constituted by the interactions among the collaborators of the organization, which have a variety of forms, such as culture, customs, among other similar results of social action within the organization. Both parts, that is, the social and the economic, are integrated through a superstructure, the functional configuration of the organization, which is the result of organizational design.

Now, concerning epistemological aspects - if intervention is allowed -, the purpose of the design of organizations is their efficiency (Simón, 1991, Rico et al., 2004), not the structure, which is the concrete product of a successful design, otherwise it would not exist as such. Mintzberg himself (1971), defines the operational functionality of organizations on administrative work, even without explaining its structure or operation.

Figure 1. The dynamics of organizational design.

Source: Self-made

The studies on organizational design have been limited to being of a hundred percent descriptive nature. This way, the study of success cases, or of companies still in progress, too much complicates theorizing the organizational design, since it is an ex post study to the conditions of failure or success, even in aspects of high uncertainty, such as, for example, institutional changes, presence of emerging economies or turbulent environments (Smets, et al ., 2012).

According to Rico and Fernández (2002), the definitions of organizational design revolve around the fulfillment of objectives. Now, this assumption establishes by default that the objectives must seek efficiency, when it is not necessarily this way, since, stricto sensu, no structure can be considered optimal, but adequate (Mintzberg, 1978); moreover, no administrator can make a decision that maximizes benefits but rather satisfies the prevailing needs, thus being an administrative and not an economic man (March and Simón, 1958).

This is an important point of the debate, based on the fact that organizations seek to maximize benefits, which they achieve by establishing objectives, focused on efficiency, which can only be achieved through an adequate organizational structure, so organic design has to be a set of structurally modifiable attributes, in such a way as to guarantee the best business performance (the concept being approached in the economic context). However, this can only be achieved through the generation of innovations, which are only required to the extent that the organization participates in highly competitive environments. In addition, a large part of the reviewed literature accepts the premise that competitiveness depends to a large extent on the capacity for innovation (Evan and Black, 1967; Swanson, 1994).

Therefore, the competitive advantage can only be the result of an organizational process of innovation, since the latter only happens if the structural conditions allow it, while the latter happens under given conditions; that is, while the organizational design allows management of innovation, the generation of competitive advantage will depend on the way in which innovations, resources and structure can generate an advantageous position for the company (See Figure 2).

Thus, the organization cannot be understood outside the system in which it finds itself, much less lose the systemic notion that it has within itself, since the main agent of any change is its organizational structure.

The structure is the result of organizational design, so it cannot be understood as a process, since it is a precedent and not a strategic asset of organizations. However, the very action of the design has a dynamic manifesto, responsible for the administrative management of the entire organization that, if observed from a market point of view, works as a company, while, if observed from an administrative perspective, it is no more than an organizational unit, the action of which is the continuity of the social interactions resulting from the design, that is, organizational development. Thus, the efficient flow of information in the organization will generate the learning that will allow its consolidation as an institution, since knowledge is not such until it is integrated in some process, activity or task, that is, when it is formalized and integrated in the organization.

Figure 2: Relationship of organizational design with competitiveness and innovation.

Source: Self-made.

This way, the organizational design serves functional activities, while organizational development corresponds to the result of the social interactions, nested in the organization. When the integration of all the elements is finally achieved, there is an institutionalization.

At this point, it is important to note that the institutional approach covers cognitive, normative and regulatory implications of the structures in such a way that stability in collective behavior is guaranteed, which is achieved through the means of control. Institutionalization is, then, in the cluster of intangible elements that make up the organization, those distinctive and connotative of it, be it, in culture, structure and organizational processes (Davis and Marquis, 2005).

4. CONCLUSIONS

So far, four concepts have been presented that contribute to the assumption that, jointly, is the theory of the organization; however, it is important to prioritize their occurrence. Simon (1991), has already presented a broad debate on the general distinctions of economic units and organizations, in which the relations of efficiency with the environment will depend on the level of social and financial transactions that take place at a given time. Thus, it does not matter whether the markets are efficient or not, but what makes them work well or badly in a given context and under what causes.

This way, you cannot establish a concept about the organization, but you can specify the relativities that it establishes with its environment and with itself. The environment is of a social nature, since market transactions are forged in the course of the economy as a collective action, whether microeconomic or macroeconomic, its general precepts are replicated in one system and another. Precisely, it is the systems approach the one that allows a broader scope on organizational theory, without the biases or limitations that restrict the case study. It can be said, then, that any organizational structure is inscribed in a system, that is why individuals -appealing to the definition of company in neoclassical economics- cannot affect the organic design, as they live it and define it under the conditions the operating system demarcates.

In order to make reference to the conciliations required by organizations towards their interior, we assume that they are rational entities (Weber, 1968), which seek to maximize their benefits through the conciliation of their members, in such a way that they cannot affect the organizational design, since they only act on the structure, generating interactions and social interrelations that are incorporated into the organization through the formalization of processes, so that institutionalization can only occur through the professionalization of the activities and social interactions, that is, through functional documentation, so that, although presented as a cultural reflex, all institutional elements are intangible, until they are integrated into the organization.

Although most of the studies on organizational design and structure per se lack an applicable universality (Barrios, 2009), the constitution of a theory of design focused on the relations resulting from the collective action of organizations, the dynamic action generated by innovation and competitiveness can offer highly satisfactory results when presented in a holistic way, since the company as an object of study only exists in the community of the market, while the organization is created in the uniqueness.

This dynamic is what determines innovation as an action resulting from external stimuli in a social micro-environment, unified by the collaboration of an end that is integrated and represented in an institutionalized symbolism (Rico and Fernández, 2002), and is projected to a macro-environment that generates greater dynamic in a virtuous circle creating living, active entities, through the action of design.

Finally, it is only necessary to add that this paper is a first approach for the construction of a theory about organizational design, in which innovation and organizational competitiveness are integrated as dynamic assets, which allow the creation and modification of organizations by establishing a bidirectional improvement system. At this point, several lines of research are opened, such as the demonstration of cause-effect generation between innovation and competitiveness, organizational design as an experimental action of efficiency, the effects of organic structures on the market economy and many others that could adequately complete a univocal theory of the organization.

5. REFERENCES

1. Aldrich, H. (1979). Organizations and Environments. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

2. Arie, L., Long, C., Caroll, T. (1999). The Coevolution of New Organizational Forms. Organization Science, 5(10), 535-550.

3. Baligh, H. (1994). Components of Culture: Nature, Interconections, and Relevance to the Decisions on the Organization Structure. Management Science, 1, (40), 14-27.

4. Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 1(17), 99-120.

5. Barney, J., Hensen, M. (1994). Trustworthiness as a Source Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal. Special Issue, 15, 175-190.

6. Barrios, D. (2009). Diseño Organizacional Bajo un Enfoque Sistémico para Unidades Empresariales Agroindustriales. Tesis de maestría. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

7. Bate, P., Khan, R., Pye, A. (2000). Towards a Culturally Sensitive Approach to Organization Structuring: Where Organization Design Meets Organization Development. Organization Science, 2(11), 197-211.

8. Bethel, J. Porter, J. (1998). Diversification and the Legal Organization of the Firm. Organization Science, 1(9), 49-67.

9. Collins English Dictionary (2009). Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. Recuperado de http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/enterprise

10. Danneels, E. (2002). The Dynamics of Product Innovations and Firm Competences. Strategic Management Journal, 12(23), 1095-1121.

11. Davis, G. y Marquis, C. (2005). Prospects for Organization Theory in the Early-Twentieth-First Century: Institutional Fields and Mechanisms. Organization Science, 4(16), 332-343.

12. Dean, J., Joon Yoon, S., Susman, G. (1992). Advanced Manufacturing Technology and Organizational Structure: Empowerment of Subordination. Organization Science, 2(3), 203-229.

13. Etzioni, A. (1975). A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations. New York: Free Press.

14. Evan, W., Black, G. (1967). Innovation in Business Organizations: Some Factors Associated with Success or Failure of Staff Proposals. The Journal of Business 4(40), 519-530.

15. Láscaris, T. (2002). Estructura Organizacional para la Innovación Tecnológica. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnología, Sociedad e Innovación, 3, Mayo-Agosto.

16. March, J., Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley.

17. Mata, F., Fuerst, L., Barney, J. (1995). Information Technology and Sustained Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based Analysis. MIS Quarterly, 4(19), 487-505.

18. Mintzberg, H. (1971). Managerial Work: Analysis from observation. Management Science, 2(18), B97-B110.

19. Mintzberg, H. (1978). The Structuring Organizations: A Synthesis of Research. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

20. Mintzberg, H. (1980). Structure in 5’s: A Synthesis of the Research on Organization Design. Management Science, 3(26), 322-341.

21. Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995).The knowledge creating company. New York: Oxford University Press.

22. Ouchi, W. (1979). A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Mechanisms. Management Science, 9(25), 833-848.

23. Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179-19

24. Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press: New York.

25. Powell, T. (1992). Organizational Alignment as Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 2(13), pp. 119-134.

26. Powell, T. (2001). Competitive Advantage: Logical and Philosophical considerations. Strategic Management Science, 9(22), 875-888.

27. Rico y Fernández (2002). Diseño de las organizaciones como proceso simbólico. Psicothema, 14(2), 415-125.

28. Rindova, V., Fombrun, C. (1999). Constructing Competitive Advantage: The Role of Firm-Cunstituent Interactions. Strategic Management Journal, 8(20), 691-710.

29. Romme, A. (2003). Making a Difference: Organization as a Design. Organization Science, 5(14), 558-573.

30. Simon, H. (1991). Organizations and Markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(5), 25-44.

31. Smetes, M., Morris, T. y Greenwood, R. (2012). From Practice to Field: A Multilevel Model of Practice-Driven Institutional Change. Academy of Management Journal, 4(25), 877-904.

32. Stabell, C., Fjelstad, D. (1998). Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks. Strategic Management Journal, 5(19), 413-437.

33. Swanson, E. (1994). Information Systems Innovations among Organizations. Management Science, 9(40), 1069-1092.

34. Teece, D., Pisano, G. y Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533

35. Walker, G., Madsen, T., Carini, G. (2002). How does Institutional Change Affect Heterogeneity among Firms?. Strategic Management Journal 2(23), 89-104.

36. Weber, M. (1968). Economía y sociedad. Esbozo de sociología comprensiva. Trad. J. Medina Echavarría. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

37. Weiss, R. (2000). Taking Science Out of Organization Science: How would Postmodernist Reconstruct the Analysis of Organizations. Organization Science. 6(11), 709-731.