doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.44.87-113

RESEARCH

INFOTAINMENT AND POLITICS: THE CASE OF THE 2015 AND 2016 SPANISH PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNS

INFOENTRETENIMIENTO Y POLÍTICA: EL CASO DE LAS ELECCIONES DE 2015 Y 2016 EN ESPAÑA

INFOENTRETENIMENTO E POLÍTICA: O CASO DAS ELEIÇÕES DE 2015 E 2016 NA ESPANHA

Marián Alonso González: Universidad de Sevilla. España.

malonsog@us.es

Recibido: 09/05/2017

Aceptado: 27/06/2017

Publicado: 15/11/2017

ABSTRACT

The 2015 and 2016 Spanish presidential campaigns have shown some transformations that affect the construction of the information message and, therefore, the practice of political journalism. The irruption of infotainment on television, the economic profitability of television politics and the versatility and youth of the new political leaders have caused candidates and advisors to be more focused on the media competition than on the ideology they represent. Publicizing the candidate, empathizing with voters and reaching audiences not interested especially in politics has become the strategy to be followed by political formations. Their objective: to carry out an exchange between the informative interest and to get the golden minute to improve their image.

KEY WORDS: Politics, Television, Infotainment, Candidates, Elections, Spain, Journalism

RESUMEN

Las campañas electorales de 2015 y 2016 en España han puesto de manifiesto una serie de transformaciones que afectan a la construcción del mensaje informativo y, por ende, a la práctica del periodismo político. La irrupción del infoentretenimiento en el medio televisivo, la rentabilidad económica de la política televisiva, y la versatilidad y juventud de los nuevos líderes han provocado que candidatos y asesores se concentren más en la competencia mediática que en la ideología que representan. Dar a conocer al candidato, empatizar con los votantes y llegar a públicos no interesados especialmente en política se ha convertido en la estrategia a seguir por las formaciones políticas. Su objetivo: llevar a cabo un intercambio entre el interés informativo y conseguir el minuto de oro capaz de mejorar su imagen.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Política, Televisión, Infoentretenimiento, candidatos, elecciones, España, Periodismo

RESUME

As campanhas eleitorais de 2015 e 2016 na Espanha puseram de manifesto uma serie de transformações que afetam a construção da mensagem informativa e, por tanto, a prática do jornalismo político. A irrupção do infroentretenimento nos meios televisivos, a rentabilidade econômica da política televisiva, e a versatilidade e juventude dos novos lideres fez com que candidatos e assessores se concentrem mais na competência mediática que na ideologia que representam. Fazer conhecer o candidato, empatizar com os votantes e atingir ao publico menos interessado em política se converteu na estratégia das formações políticas. Seu objetivo: levar a cabo um intercâmbio entre o interesse informativo e conseguir o minuto de ouro capaz de melhorar sua imagem.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Política, Televisão, Infoentretenimento, Candidatos, Eleições, Espanha, Jornalismo

How to cite the article

Alonso González, M. Infotainment and politics: the case of the 2015 and 2016 Spanish presidential campaigns [Infoentretenimiento y política: el caso de las elecciones de 2015 y 2016 en España] Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI; 44, 87-113. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.44.87-113

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/488

1. INTRODUCTION

Political communication is “the exchange and confrontation of the contents of public-political interest produced by the political system, the media system and the citizen-elector” (Mazzoleni, 2010: 36), so that the purpose of politics is to reach and influence a third party (public opinion) through an intermediary-channeler who is the means of communication, because “what does not transcend the media does not exist” (Lluch, 2015, p. 115).

This dependence on the media policy to transfer its message to the citizenry has given rise to what is known as “media democracy”, a term coined by Muñoz-Alonso and Rospir (1999) to refer to the relationships established between democratic systems and the mass media, especially radio and television.

The media appear in this model as responsible for the construction and channeling of public and political agendas, as the great mediators between political-social actors and public opinion (Badillo and Marenghi, 2001). In this same vein, Viladot (2008) affirms that the media are opinion makers and, therefore, “their importance is paramount, especially in relation to politics during the electoral campaigns.”

More than ever before, viewers know a multitude of facts, events, experiences, and they participate emotionally in them, they feel involved, but “only about what they have captured through the mass media,” say Abejón et al. (2013).

Though cyber-campaigns have shown that the network has a positive influence on the electoral results and that the candidates with better social media positions can outperform their opponents, television remains being the optimal medium to let candidates be known, consolidate parties and amplify their messages.

In this sense, Fernández Torres (2005) states that, as the vision is the meaning that provides a more direct experience of things, television gives off the feeling that what is seen in it is reality and, therefore, it contributes powerfully to form public opinion.

The image dominates over reflection and renders everything that does not appear on the screen outdated. It seems that it is not possible to imagine our world without television, the most powerful disseminating means of audiovisual messages to date and the easiest and most convenient way to distribute content.

Last year, Spaniards watched television on an average of 3 hours and 48 minutes a day (4 minutes less than the previous year), according to data from Kantarmedia (2016). The cumulative audience was 44,440,000, that is, 99.8% of viewers over the age of four watched some minute of television, and only 0.2% did not tune in their receiver at any time (89,052). As a daily average, it was 32,677,000, which means that 73.4% of the population watches television daily (Barlovento, 2016).

The months of January and February were those of greater consumption, with an average of 255 and 251 minutes, respectively. Women (243 minutes) and those over 64 (351 minutes) were the targets that spent more time watching television. By chains, Telecinco was the most viewed for the fifth consecutive year, obtaining 14.4% of the screen quota and being ahead of Antena 3 (12.8%), TVE1 (0,1%), La Sexta (7 , 1%) and Cuatro (6.5%).

The data presented herein give an idea of ??the media strength of television in the media in Spain, due to the power of the image, but also because of its tireless work of entertainment.

1.1 Politics and television

The bond between politicians and television was born in the United States. Its business conception on a private basis and an eminently commercial spirit quickly turned television into the ideal medium for developing Eisenhower’s presidential campaign in 1952. The television spot that played with his nickname “Ike” to turn it into the slogan “Like Ike,” with which he won the election, was the starting point for a new way of conceiving political communication.

There was thus a new way of conceiving political communication:

It marked the end of the long speeches that the radio had left in inheritance to the first televising broadcasts, giving birth to a language more emotional than that of the press, in which the image also came into play and which demanded extreme clarity and concision, because the public had no chance to go back to “reread” what was being said (López, 2011, p. 3).

Thereafter, a new way of understanding “media democracy” is developed and, therefore, a new form of public discourse structuring in which the word ceases to be its only constructive element, as it happened in the press or on the radio, to rely also on the image.

“The main agent who has transformed the path of politicians is television” (Berrocal, 2005, p. 55) to become “one of the great means of political communication to get messages reach the public and to improve the positioning of a governmental action “(Costa, 2008, p. 259).

One of the first researchers to place television at the heart of the relationship between politics and communication is Cayrol, who, as early as 1970, warned that television is the mass medium preferred by voters, since no other means allows politicians to have better access to the universe of citizens and, therefore, television “strongly conditions the use of the other forms of Political Communication, since they are designed according to their television” (Martínez Pandiani, 2006, p. 71)

The preponderance of the audiovisual formats over the textual ones has caused “television to be the public space most consulted by citizens when defining their conduct in the polls” (Fernandez, 2015, p. 281) and, by virtue of it, the different parties try to construct an image of the candidate according to the preferences of the audience:

It is about building an image of the candidate, sifted through television, that is appealing to the electorate. The important thing is how to say things. Aspects such as clothes or gesturing coexist with others such as trajectory, ideology or family. (Fernandez, 2015, p.284)

This importance of television in the field of political communication causes the term “media democracy” to give way to a “visible democracy” or to “telepolitics”, a concept that must be studied in a broader sociological context and the defining features of which are identified by Martínez Pandiani (2006) as:

– Mediatization of politics: Faced with the decline of partisan affiliation, the mass media are transformed into the political information powerhouse most consulted by citizens when it comes to making electoral decisions.

– Making politics audiovisual: Marked preponderance of audiovisual formats versus textual formats and which allows the term “videopolitics” to be coined.

– Spectacularization of politics: Television imposes its logic of entertainment and prioritizes the emotional impact and staging. It turns the leader into an “actor” in the media arena that plays a role not so much determined by the needs of its party group as by the demands of the media.

– Personalization of politics: The electorate tends to evaluate their voting options according to criteria more linked to the individual image and its personality than to their party or ideological belongings.

– Marketization of politics: Use, in the political campaigns, of sophisticated communication and marketing tools that privilege “how to say” over “what to say”.

The fact that television unifies all the variables of the political discourse and turns them into spectacle or entertainment has caused what is anecdotal to stand in the foreground in order to obtain electoral revenues through that humanization of the candidate:

The candidate on a bicycle; the candidate responding with calculated vehemence to a citizen who spits out to him in the middle of the street; electoral videos where the pathos is brushed by seeing how someone who aspires to govern an institution plays a rap; cameos in television series; appearances in magazines ... (Fernandez Obregón, 2015, page 284).

Within this context, electoral campaigns have been turned around so that, where the content of the program used to prevail, it is now decided to give importance to the candidate, so that this relationship between politics and image “elevates communication cabinets and image advisors to a much more relevant role. A media and more iconic policy” (Valencia, 2015, p.27).

This new policy, says Valencia, is attractive to the media because it has an audience but, above all, because the politician “enters the game of the media, in particular, the logic of mass entertainment” (2015: 28) arriving at a new informational stage that could be denominated entertainment in which the policy is:

Less discursive and much more emotional; less cerebral and more attentive to rhetoric; a policy that loses abstract density and imbues itself with the lightness of everydayness (...) which also serves to popularize and extend values ??and meanings which would otherwise be the exclusive consumption of certain social elites (Vallespín, 2012, p. 146).

Politics as a spectacle has made, as Contreras (1990) states, campaigns be considered mere commercial promotions and the viewer be studied as a new market niche, which is why the image of the candidate is a mirror of power in this media world.

The origin of marketing in the election campaign is found in the 1960 American election in which Kennedy defeated Nixon during a televised debate in which he appeared in makeup, tanned, smiling and in an impeccable suit versus a Nixon without shaving and with the same suit after a whole day of work.

Weber said that politicians are entrepreneurs who mobilize resources, finance, affiliates and voters, turning parties into bureaucracies (Alvarez and Pascual, 2002) and. for this purpose, they do not hesitate to mediate politics and, in this sense, nothing is more effective than reinforcing the more humane profile of the candidate, thus creating a “feeling of closeness, commitment, availability and gift of people that can contribute to clear the doubts of the indecisive sector” (Quevedo et al, 2016, p.101).

That is why, despite the rise of social networks, politicians still rely on television to carry their political messages, to the point of reducing their rallies and other traditional acts to promote their television presence. This is the case of Pablo Iglesias who, during the past legislative years, practically renounced “half of the electoral acts to focus on his appearances in the medium that popularized him, as party strategists consider it to be the most profitable and influential showcase to gain votes “(Carvajal, 2016).

Image dominates reflection and renders everything that does not appear on the screen outdated. It seems that it is not possible to imagine our world without television, the most powerful audiovisual disseminating media to date, capable of generating personal ties with citizens while, at the same time, getting voters to simply consume political content (Wolton, 1995).

The media strength of television in the mass media in Spain is due to the power of the image, but also to its tireless work of entertainment, which has led to the appearance of new programs of political content but oriented to the show, privileging informal, personalized and spectacular content (Thusu, 2007).

The spectacularization of the information and the commercialization of the feelings have caused the dissolution of borders between the genres and a mixture of contents generating a change in the discourse of the television, which moves away from the reproductive model of reality to approach a model producing reality.

The informative hypergenre thus arises, the one that combines entertainment, variety and fiction, from them the infoshow and infotainment stand out, their main difference being that entertainment is given priority in the former case, while information predominates in the latter case (Luzon and Ferrer, 2008).

Infotainment has a prominent position in the programming grids of the main generalist channels of Spanish DTT. In fact, “the total weekly time devoted to this genre is 153 hours and 58 minutes” (Berrocal et al., 2014: 94), La Sexta (34.91%) and Telecinco (22.66%) being the chains that top out the weekly time ranking dedicated to this hypergenre.

The mix of infotainment and politics is a trend that we have imported from the United States in which the political message succumbs to the culture of the spectacle, so that the politician no longer only thinks about the voters, but also on the TV viewers. Thus, politainment arises (Nieland, 2008; Sayre & King, 2010; Schultz, 2012), it is a term that is closely associated with politics and is a direct consequence of citizen political disaffection (Ntutumu, 2015).

Politainment brings together two functions relating to the media such as information and entertainment, two objectives that, in principle, could be considered opposites, but which often go hand in hand.

This hybridization, “understood as a mixture of ideas or formats” (Alonso, 2017: 75), has been one of the basic tools to create and innovate in all areas, that is why it could not be lacking in television, an essential public service the purpose of which, as set out in the Spanish legal system in Article 128 of the Spanish Constitution, must be “to satisfy the interest of citizens and to contribute to informative pluralism, to the formation of a free public opinion and the extension of culture”.

1.2. The Spanish case

Until the elections of November 2015, the model of political campaign in Spain was limited to the one imposed in 1940 by Winston Churchill who, through the word, appealed to the emotions and tried to identify himself with the receiver through the rhetorical recourse of repetitions. However, the electoral campaigns of 2015 and 2016 have shown that, although rallies are still a key tool for mobilization since they are capable of generating credibility, trust, leadership and enthusiasm; television is the means of communication that reaches the majority of citizens who exercise their right to vote.

Its success lies in the fact that proximity is a source of credibility, and television influences to bring politicians closer, for good and for bad and, therefore, more credible or not. Thanks to this quality, television has become the “queen of the tools of Political Communication,” according to Micovic (2014), who says that fifteen seconds on television are more effective than three articles of opinion, two interviews on the radio or many communicative activities in the network, which would explain why television, in its various formats, has been hugged strongly by a new political class that knows of telegenetic quality and how to look at the camera.

With the reign of television in the world of social communication, the centrality of the leader in front of the organization is a fact:

The leader and his group of advisors focus more on the media competition than on the traditional workings of party life. Television has been in charge of banishing the power of the brand or party and of turning the electoral contest into a crossroads of images of people. That is to say; the dictatorship of form over the background (Fernández, 2015, p.279).

In the infotainment era, the three basic functions of television: informing, entertaining and forming (Bobo, 2005) are intermingled to give rise to new narratives and audiovisual forms that transcend the genres we have traditionally known. In this sense, and based on the premise that a piece of news offered by infotainment techniques captures the attention of the audience better than another presented in a traditional way (Grabe et al., 2000), the last two electoral campaigns in Spain (November 2015 and June 2016) have shown that television has become the priority objective of the candidates for the Spanish presidency, who follow the prevailing patterns of what some authors such as Ramonet (2002) and Franco (2011) have called “ of politics”.

Now the image and, by the same token, the capacity of seduction, is imposed to eloquence and argumentation. Now the leader is not only so due to his intellectual, economic or political qualities, but especially due to his media capacity (Laguna, 2011, p. 47).

From 1975 until the elections of June 26, 2016, there have been 12 legislative elections in Spain and only six televised electoral debates, a figure that shows the little tradition of political confrontation on television; in fact, on only three occasions there were debates among the candidates to occupy La Moncloa.

The possibility of holding electoral debates was gradually frustrated election after election for various reasons. Blanco says (2015) that:

In the pre-legislative dates of 1979, both Santiago Carrillo and Felipe González challenged Adolfo Suárez to debate, but the then president rejected such possibility. Shortly before the elections of 1982, the demands of the PSOE were the ones that brought about the disagreement for the celebration of a debate that the Electoral Board had already approved.

The beginning of private television in Spain entails a change in the trend and so, on May 24, 1993, the first face-to-face between Felipe González (PSOE) and José María Aznar (PP) is broadcast in Antena 3, while the second took place a week later in Telecinco. Moderated by journalist Manuel Campos Vidal, it was watched by an audience of nearly 10 million people.

15 years would have to go by for a new face to face on television among the candidates for the presidency of the Government of Spain. Thus, before the March 9, 2008 elections, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) and Mariano Rajoy (PP) faced each other at the Television Academy, the signal of which was offered free of charge to all channels interested in issuing it. Manuel Campos Vidal and Olga Viza were in charge of moderating the two debates that were followed by 13 million spectators. Subsequently, and in identical conditions, that is to say with Campos Vidal as a moderator and organized by the Television Academy, in 2011 there was a single face to face between the aspirants to La Moncloa: Mariano Rajoy (PP) and Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba (PSOE), followed by 12 million viewers.

2. OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESIS

The starting hypothesis of this paper is that television has become the means par excellence used by the candidates to reach the emotions of their voters and, for this purpose, they do not hesitate to give priority to their television appearances in formats of infotainment to other acts of campaign.

Based on our initial hypothesis, we have defined a general objective, which is to identify the degree of presence that politicians have had on TV and the type of programs that constitute their niche of interest.

For this purpose, we have established the following secondary objectives:

1. Quantify the television appearances of politicians during the election campaigns of 2015 and 2016.

2. Identify the television channel that has spent more minutes.

3. Identify the programs to which candidates go and determine if they fall within the informational or infotainment genre.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve the stated objectives, as well as to verify or refute the starting hypothesis of this paper, we have used a mixed research method that corresponds to a combination of quantitative and qualitative techniques that provide greater rigor and value to research since both complement each other.

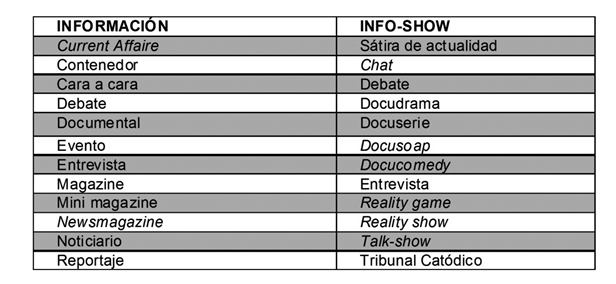

In this sense, we have analyzed the content of the program and a qualitative study of media products following the textual analysis proposed by Casetti and Odin to “highlight the architecture and the functioning of the analyzed programs, the theoretical structure that supports them and the strategies they deploy “(1997: 249). Likewise, we have analyzed the programs that the candidates have attended in terms of format (informational or hybrid) and gender; for this purpose, we have used the classification established by Euromonitor, and used by Berrocal et al. (2014: 93): Fiction, Information, Infoshow, Show, Contest, Sports, Children, Juvenile, Education, Religion and Miscellaneous. Of these, the two macrogenres Information and Infoshow that are related to infotainment and are listed in Table 1 have been selected.

Table nº 1 Genres of Information and Info-show

Source: Berrocal et al. (2014, p. 93)

For a correct longitudinal study, we have chosen the programs which the four candidates for the Presidency of the Government and their first swords have attended in the periods from October 27 to December 18, 2015 and from May 3 to. June 24, 2016, that is to say, from the day the decree of dissolution of the courts is published in the BOE and enters into force and the new elections are called until the end of the electoral campaign. In total we have analyzed a total of 116 speeches in programs broadcast in five national channels, one public (TVE 1) and four private (Antena 3, Cuatro, Telecinco and La Sexta).

4. RESULTS

The emergence of new citizen parties in the Spanish political spectrum has led to the leap towards conversation and mobilization, while social networks have been placed in a central position within the machinery of dissemination of political slogans with the key support of television and political debate programs.

This has also been contributed by a significant change in the profile of politicians who have attended the last two General Elections in Spain. Young, dynamic and with work experience outside the political sphere, the candidates for the Presidency of Spain do not older than 45 years and can fit within Generation X, a term coined by the photographer and journalist Robert Capa and popularized by Douglas Coupland (1991 ) thanks to his novel Generation X: _Tales for an Accelerated Culture.

Except for Mariano Rajoy, who is over 60, the oldest is Pedro Sánchez, 44, followed by Pablo Iglesias (37) and Albert Rivera (36). All of them share the fact of having been witnesses of honor in the transition from the analogical to the digital technology and having played a key role in the technological development in which we are now submerged.

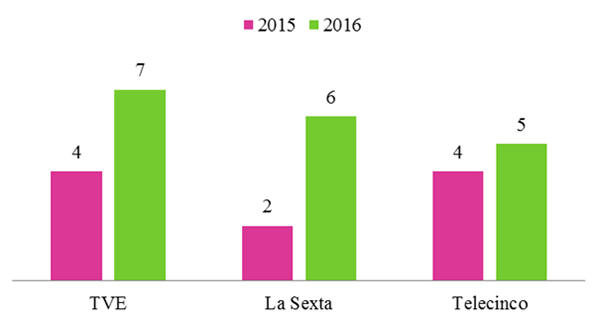

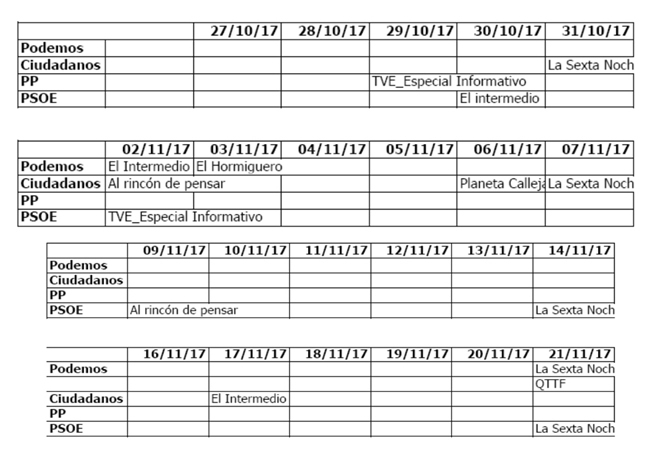

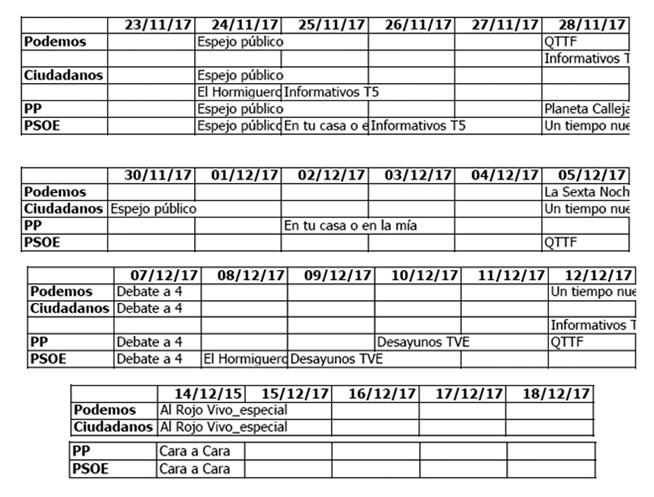

During the last two electoral campaigns (December 2015 and June 2016), this change of politicians, media and candidates has caused the leaders of the main political formations of our country to have participated in 116 television spaces. Out of them, 48 took place in 2015 and 68 in 2016, which means 58.6% of more television appearances in just six months of difference.

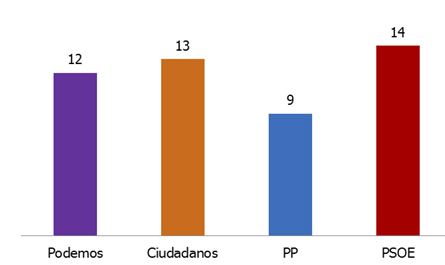

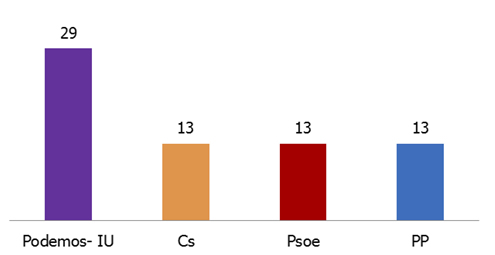

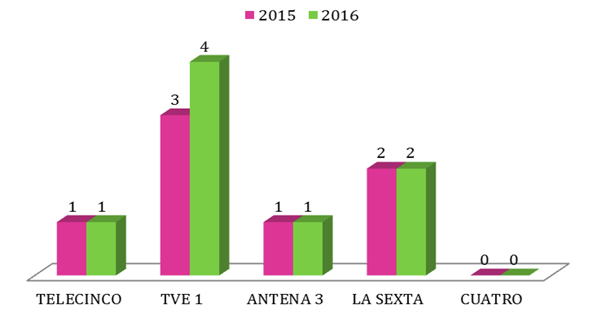

If, in the 2015 election, the number of television appearances is quite similar in all political formations (see Figure 1), during the 2016 elections the party led by Pablo Iglesias (Podemos) has been the one with more presence on television, almost doubling that of 2015, appearing in a total of 29 broadcasts (see Graph 2), while the other parties have maintained a similar tone.

Graph 1. Presence of the parties on television 2015 Elections

Source: made by the author

Graph 2. Presence of the parties on television 2016 Elections

Source: made by the author

The bulk of information during the first elections was concentrated in the fortnight of November 24 to December 7, where 56% of TV appearances are accounted for. That same fortnight, 10 days before the elections, it is once again the favorite of politicians during the 2016 elections to focus their appearances on television. Specifically, from 31 May to 13 June, 30 out of the 68 appearances of these second elections occur.

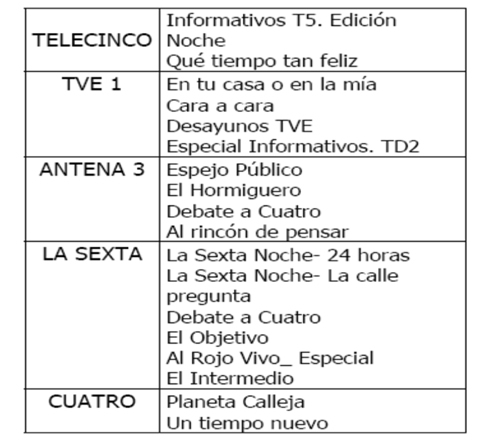

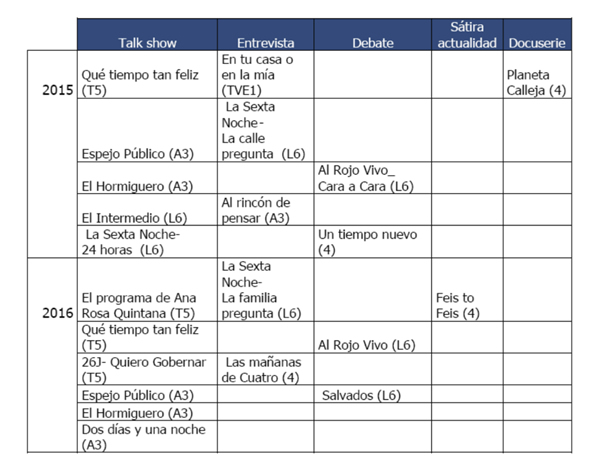

During the 2015 campaign, the candidates attended 17 different television programs, predominantly La Sexta (6), followed by TVE (4), Antena 3 (4), Telecinco (2) and Cuatro (2) (See Table 3).

Table nº3 Programs attended by candidates 2015 Elections

Source: made by the author

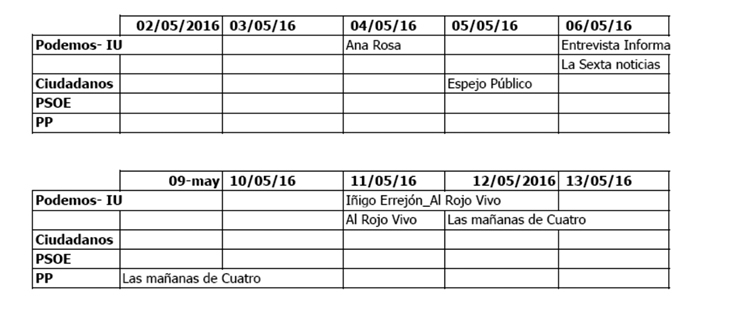

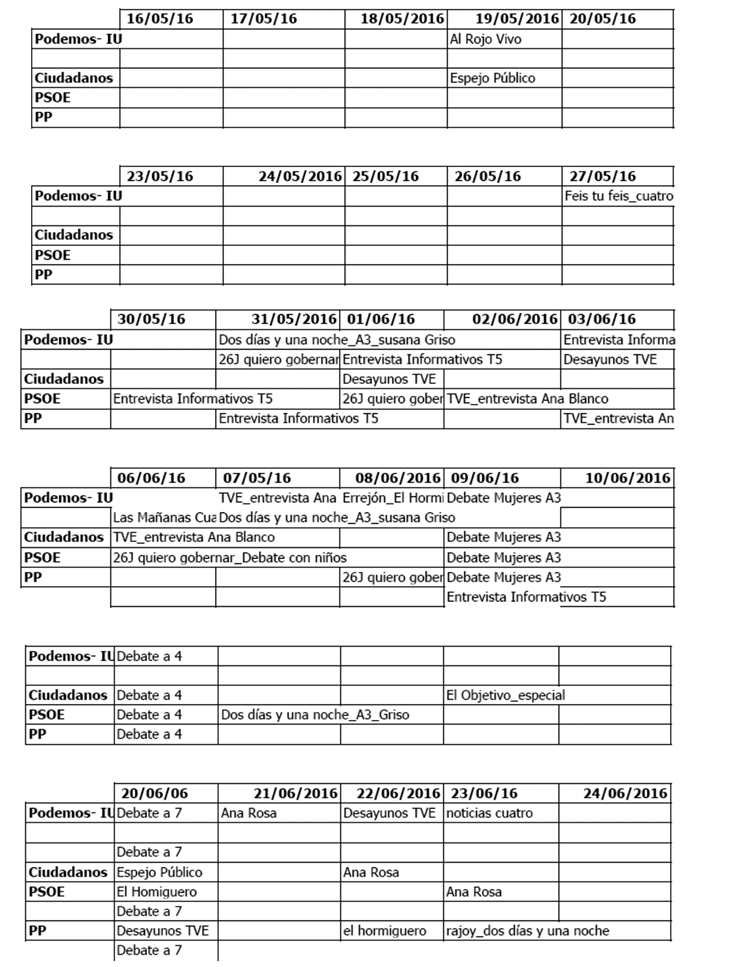

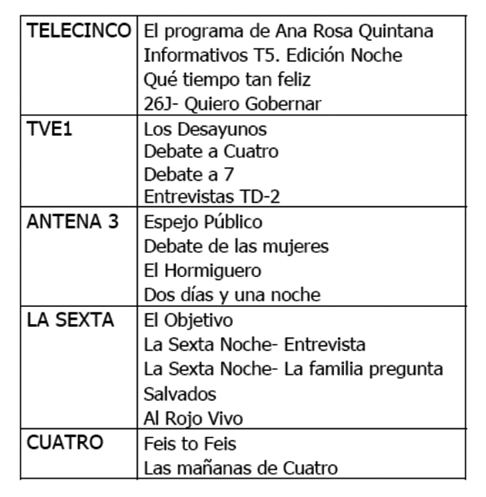

As can be seen in Table 4, La Sexta is once again the broadcasting station that dedicates more programs to political information in 2016 (5). On this occasion, the candidates went to 19 television programs distributed by chains such as Telecinco (4), TVE (4), Antena 3 (4), Cuatro (2).

Table nº 4 Programs which the candidates have attended

Source: made by the author

4.1. Information Programs

By type of format, presidential candidates attended 7 news programs during the election campaigns of 2015 and 2016. In percentage terms, and taking into account the total number of television appearances, pure information programs are 44% of the programs of the campaign elections in 2015 and 37% in 2016. By chains, this type of formats has predominated in the public channel TVE1, where 7 out of the 14 programs were developed. In both elections, Cuatro was the only chain in which no information program was broadcast (see Graph 3 and Table 5).

Graph 3. Number of information programs. 2015 and 2016 Elections

Source: made by the author

Table nº 5 Information programs that the candidates attended

Source: made by the author

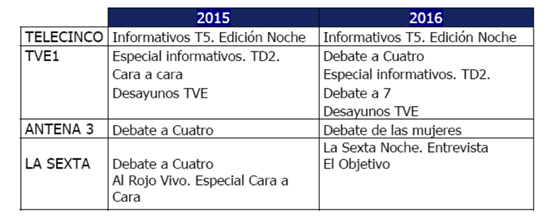

At the gender level, the interview and the debate predominate. The interview is “the format most used in our country, and it is the one that has the presence of the political leader on television, answering the questions of one or several journalists” (Berrocal, 2005, p.4).

During 2015, a total of 10 interviews were broadcast, 4 out of which were made in TVE, 4 in Telecinco and 2 in La Sexta. Just six months later, during the 2016 campaign, the number of interviews increased to 18, TVE (7) leading, followed by La Sexta (6) and Telecinco (5) (See Graph 4).

Graph 4. Interviews conducted by chains Source: made by the author

Within the informative format, we have included the interviews that were framed in informational spaces such as newscasts, this is the case of the interviews conducted by Pedro Piqueras in the night edition of “Informativos Telecinco” and those by Ana Blanco in the “Telediario-2ª edition” of TVE, which dealt with issues such as the threat of jihadist terrorism, the latest news on the sovereignty challenge in Catalonia and its main proposals in the political, economic and social field for the next legislature.

In the field of political interviews, in depth, it is worth mentioning those made by Ana Pastor in “El Objetivo” (La Sexta) to Pablo Iglesias (Podemos) and Albert Rivera (Ciudadanos) and by María Casado in “Los Desayunos de TVE” to the four presidential candidates, as well as those conducted by Iñaki López in “La Sexta Noche”.For its part, the debate is the gender preferred by the candidates of the recent democratic history of Spain. During the last two elections, we have attended a total of 5 traditional political debates which can therefore be framed in the informative format. Out of them, two took place during 2015, and the remaining three in 2016. By chains, TVE and the group Atresmedia, are the leaders in this type of formats.

– 07/12/2015. Under the name of ‘7D: the decisive debate’, the four-party meeting between the main political parties was broadcast simultaneously on Antena 3 and La Sexta in prime time. Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría (PP), Pedro Sánchez (PSOE), Albert Rivera (Ciudadanos) and Pablo Iglesias (Podemos) participated. Hosted by Ana Pastor and Vicente Vallés, it was a novel format where there was room for “re-questioning” among politicians and moderators, as well as a “room of time” that controlled how many minutes each representative used in their interventions to corroborate that everything was equitable.

Another innovation was to allow the audience to track the candidates from the minute they got in their cars to reach Atresmedia studios. As if everything was a reality show, Pedro Sanchez could be seen reviewing with his wife; Soraya Saénz de Santamaría chatting amicably with one of her trusted people; Albert Rivera accompanied by more than 6 people; Pablo Iglesias and Íñigo Errejón without a safety belt…

– 12/14/2015. Classical face-to-face format between Mariano Rajoy (PP) and Pedro Sánchez (PSOE). Organized by the Television Academy, it was hosted by Manuel Campos Vidal, the arbitrator in three out of the five debates between candidates for La Moncloa, broadcast simultaneously by TVE, La Sexta and Antena 3. With duration of 110 minutes and a break for advertising, the debate was opened by the Socialist candidate and closed by the President of the Government.

– 06/09/2016. For the first time, four women lead a debate in the electoral campaign. “Women first,” broadcast by Antena 3 and hosted by Vicente Vallés, brought together two candidates for the elections, Margarita Robles, PSOE and Carolina Bescansa, and two deputies in the Parliament of Catalonia, Andrea Levy, PP; and Inés Arrimadas, Ciudadanos.

– 06/13/2016. Organized by the Television Academy and moderated by Ana Blanco (TVE), Pedro Piqueras (Telecinco) and Vicente Vallés (Antena 3), it is the first and unique debate in the history of Spanish democracy that has brought together the four presidential candidates. The debate was structured around a presentation of presenters and candidates, three blocks (Economy, social policies and democratic regeneration, and international relations and refugees), a final coda and request of vote on the part of the candidates that started with Pablo Iglesias, followed by Albert Rivera, Mariano Rajoy and Pedro Sánchez.

– 06/20/2016. “Debate to seven” organized by RTVE and moderated by Julio Somoano in which seven representatives of the parties with presence in Parliament - Pablo Casado (PP), Isabel Rodríguez (PSOE), Juan Carlos Girauta (Ciudadanos), Íñigo Errejón (Unidos Podemos), Aitor Esteban (PNV), Carles Campuzano (CDC) and Gabriel Rufian (ERC) - confronted their political programs. The presence of nationalist parties focused on the place of Catalonia within Spain and the formulas of the different formations.

4.2. Infotainment programs

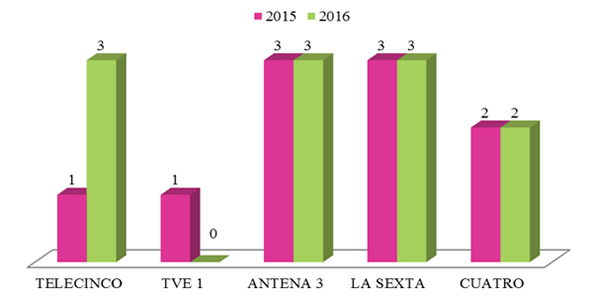

56% and 63% of the programs broadcast during the electoral campaigns of 2015 and 2016 can be included within infotainment. This entails 10 and 11 programs, respectively. By chains, if during 2015 Antena 3 and La Sexta tied with 3 programs each, during 2016, Telecinco joined this short list, while TVE passed from one to no program of these characteristics (See Graph 5).

Graph 5. Infotainment programs by chains Source: made by the author

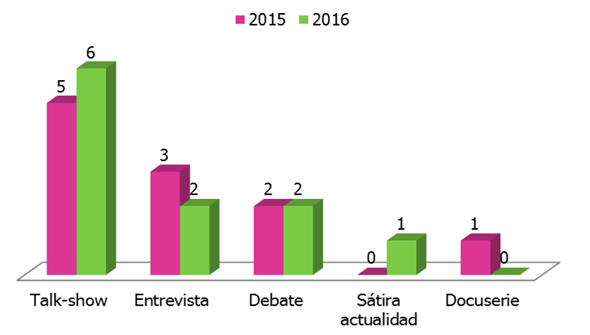

By genres, and according to the categories identified by Euromonitor and collected by Berrocal et al. (2014, p. 93), within the scope of the Info-Show, the Talk-shows prevail during both campaigns, followed by the interviews (see Graph 6 and Table 5).

Graph 6. Infotainment programs. 2015 and 2016 Elections

Source: made by the author

Table nº 6 Classification infotainment programs. 2015 and 2016 Elections

Source: made by the author

4.2.1. Talk shows

Within the group of Talk shows are the programs that Gordillo et al. (2011: 104) denominate show of varieties and which are based on the figure of the star presenter and fixed collaborators who, using the model of magazine, include the superficial treatment of current events.

– What a happy time.

It is a magazine produced by Mandarina for Telecinco, and presented by Mª Teresa Campos, in which artists, television programs, musical styles ... of success in the past of Spain are remembered. During the electoral campaign of 2015, the journalist interviewed Iglesias, Sánchez, Rivera and Rajoy in the space in order to show the human side of the candidates through anecdotes and personal passages. In fact, the interview with Rajoy included images of him on television 19 years ago and photos of his childhood, while Pablo Iglesias took a guitar and dedicated to the presenter a nana taught to him by his mother.

– Public mirror

A magazine morning container led by Susana Griso since 2006 that is based on current events and the live. The program includes articles on topics, news of public interest that are part of the headlines in the media and political interviews.

– The intermediate

Presented by The Great Wyoming is a satirical program that analyzes current events with humor and interweaves different characters in other styles. The socialist candidate, Pedro Sánchez, passed by its set in 2015, who spoke of the impossibility of a coalition between PP and PSOE; Albert Rivera, who avoided positioning himself on the decision to remove the Francoist plates from the streets, and Pablo Iglesias, whom the humorist asked about his sex life after declaring in the program of Risto Mejide that he tries to have sex during the election campaign and then to assure in the program of Jordi Évole that he is tired.

– Two days and one night

Adapted from “Sleeping with the stars”, this is a talk show where the guest also acts as a host. The journalist Sussana Griso is in charge of visiting the house of the person where she moves in for two days and one night in order to, through coexistence, go shelling the life of the famous person. Griso interviewed Pedro Sánchez in the electoral bus, Pablo Iglesias at the institute where he studied in the Madrid neighborhood of Moratalaz and she got Albert Rivera to talk about sex, his ex-wife and his daughter. Iglesias with a share of 10.9%, and Albert Rivera with 9.6% were the politicians who reached the highest audience.

– The Anthill

It is a Talk Show broadcast by Antena 3 and presented and directed by Pablo Motos that can be defined as a “cocktail in which entertainment and information are mixed, understanding this in the widest spectrum of the media-followed current events” (Gordillo et al., 2011: 101 ). During his visit, Pedro Sánchez danced break dance, Pablo Iglesias sang and played the guitar, while the vice president of the government dared with the choreography of Uptown Funk, Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars; getting the #SorayaEH hashtag to be Trending Topic.

– Ana Rosa Quintana’s program

A television morning magazine produced by Quarzo for Telecinco that approaches current events from different perspectives: interviews, investigative reports, gatherings and discussion tables.

– 26J- I want to govern (T5)

A talk show moderated by Ana Rosa Quintana in which the four candidates answered the questions not agreed and formulated by children being 5 to 12 years old. The minors also had the opportunity to comment on the Spanish reality and contribute their point of view on the political situation, while a minor disguised as the candidate, in the purest “miniyo” style, made him a kind of self-interview.

– Sixth Night- 24 hours

Within the program of political talk, there is a section called “24 hours with” in which a report on the 24 hours that the presenter of the program, Iñaki López, spends with the presidential candidates of PSOE, Podemos and Ciudadanos, is broadcast. Through this accompaniment, we could know the relationship Pablo Iglesias with the press and the media or the fact that Pedro Sánchez misses being able to see his daughters more often due to the intense pace imposed by the electoral campaign, something about which Albert Rivera complained too, who confessed the difficulty of being a father and a presidential candidate and the fact that he reserves Wednesday afternoon exclusively for his daughter.

4.2.2. Interviews

In the field of the infotainment interviews, we have framed those programs that have offered interviews of the personality of the electoral candidates by joining information and entertainment with clear elements close to the infoshow and the magazine interview.

– To the thinking corner

Presented by Risto Mejide, it is an interview format that Albert Rivera and Pedro Sánchez attended in the midst of the 2015 election campaign, Pablo Iglesias had previously been there. The former revealed his more personal facet, with references to his ex-wife, his daughter and his fears, while Sanchez recognized that his weak point was the emotional barriers.

– Your place or mine

Presented by Bertín Osborne, it is a program broadcast by TVE1 that lays emphasis on “interviews with a personal theme and where the level of protagonism of the presenter is high, to the point that the topics refer to both the personal and professional field of the interviewer and the interviewee “(Alonso, 2017: 81). Osborne only interviewed the leaders of the majority parties: PSOE and PP. With Pedro Sánchez, he finished playing table tennis, while Mariano Rajoy achieved the golden minute when he explained how his life at the Palacio de la Moncloa is, a moment seen by 4,710,000 spectators.

– The Sixth Night- The street asks (L6)

Following the wake of TVE mythical program “I have a question for you”, this special section is enabled in the program “Sixth Night” in which leaders of the political formations answer the questions asked by the Spaniards chosen by a demographic company. Rajoy, Sanchez, Iglesias and Rivera passed through this section. Iglesias answered his cousin Diego’s question about the future of the self-employed if Podemos won; Sánchez was put in a predicament by a housewife who asked him if he knew the names of the tutors of his daughters, Rivera had to face a citizen who asked him what he was going to do so that his grandfather would come out of a common grave, while Rajoy was hesitant when asked about Rodrigo Rato.

– A new time

A program of debates presented by Silvia Intxaurrondo that mixes political, economic and social analysis with investigative journalism. On the occasion of the December 2015 elections, Sánchez, Rivera and Iglesias were present.

– The Sixth Night- The family asks

Following the style of “The Streets Asks”, the format was updated for the elections of June 2016, with several families with components belonging to different generations passing to interview the candidates. The most remarkable thing about Sanchez after facing 6 families was his resounding no to the grand coalition; for his part, Iglesias said he did not want Catalonia to leave Spain and resorted to the PSOE again to create an alternative government; while Rivera responded to the citizen boredom by the repetition of elections and recognized that failing to have obtained the rapprochement between PSOE and PP had been a mistake. Mariano Rajoy declined the offer to participate in this space.

– Mornings of Four

A program including current events and social gathering that is presented by Javier Ruiz and pays special attention to a political table; it is broadcast in Cuatro Monday through Friday from 12.30 to 14.15.

4.2.3. Debate

– Saved

It is an interview program on current issues hosted by Jordi Évole, which gives a critical tone to the most controversial issues. Ten months after the so-called “first debate on the new policy”, the leaders of Podemos and Ciudadanos gathered in the Circle of Fine Arts to discuss their political ideas. During the course of the program, the host presented different topics on education, health, the refugee crisis, employment or the adjustments claimed by Brussels.

– Red Hot: Face-to-Face Objective

A special program with the presence of Albert Rivera and Pablo Iglesias to discuss the classic debate between Mariano Rajoy and Pedro Sánchez, which was held on December 14, 2015. It sought to break with the “bipartisan” concept imposed by the Academy with the debate by two. The leaders of Ciudadanos and Podemos commented on the words of the candidates of the traditional parties and were questioned by Ferreras in a sort of “counterdebate”.

– A new time

Presented by Silvia Intxaurrondo, it was the only program that had a debate including the six representatives of the main parties, who addressed the challenge of Catalonia, democratic regeneration and corruption, among other issues.

4.2.4. Current satire

– Face to face

A program based on the format “How to Be” that triumphs in Israel, Sweden and Germany. Presented by Joaquin Reyes, it is a program of “self-interviews” in which the humorist takes on the role of alter ego of each guest and assumes his personality, way of speaking and more characteristic tics. The actor imitated Pablo Iglesias and, in order to know him in depth, he dived for a few days in his most intimate circle. The workload, a supposed reform in La Moncloa or the problems with Errejón to get into the discotheques were some of the questions faced by the humorist.

4.2.5. Docuseries

– Planet Calleja

A format of adventures of Jesus Calleja that, along with famous personages, crosses the world geography, with all its fauna and flora and the dangers that it entails. With Pedro Sánchez he climbed the Rock of Ifach, with Albert Rivera he participated in the Rally of Baja de Aragon, where they had a spectacular accident; while Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría accompanied him on the Road to Santiago and had a small mishap when traveling in a balloon, which ended up crashing after brushing a tree and a street lamp.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Spanish politicians have found on television a great ally to convey their political slogans, but also to win supporters and voters based on affinities and sympathies.

Showing the human side of the candidate has become a new way of getting popularity among future voters, close approaches that, as Ortells (2012) states, “push the informative message away from its original purpose, contribute to the political debate and create public opinion”

In this sense, the commitment of the presidential candidates to appear on television programs is significant, to the point of doubling their presence in that medium, as is the case of Pablo Iglesias de Podemos, who, in both electoral campaigns, had up to 40 television interventions.

Although candidates continue laying emphasis on the pure informative formats in which interviews and debates prevail, during the electoral campaigns of 2015 and 2016 we have witnessed a new phenomenon in Spain, the spectacularization of the television policy.

All channels, except Televisión Española, because of its character of being a public service, have chosen formats that adapt infotainment to politics and in which the border between what is public and what is private is dissipated to give way to contents that show the human side of the candidate in order to compete for as many viewers as possible.

This has been possible thanks to the versatility and youth of the new leaders, who have made it possible a new way of campaigning, but also to the consolidation of the private chains that have been able to see profitability in politics.

If you had to go to the rallies before to get contagious with their emotions, they are now the ones who do not hesitate to go to the television to directly, massively and continuously show their most human side, to talk about their personal life, their family and to address the topics of interest in a more superficial way.

Politicians have become a product and both they and the media themselves derive benefits. Thanks to television, candidates can come and motivate to vote to a niche of voters alien to the political debate. Their objective is to convey light political information of easy consumption, loaded with emotion and using techniques of storytelling to carry out an exchange in the informational interest and to obtain the golden minute capable of improving their image.

Politics sells and the private life of the politicians sells even more; that is why, in the last two election campaigns, we have seen that there has been an increase in infotainment programs (more than 60% in the 2016 campaign), which have welcomed politicians, formats of political content but oriented to the show, they are more interested in letting the candidate be known than in spreading their electoral programs to the point that the personal qualities of the leader come to be in a hierarchical level superior to the ideology that he represents; at least as far as media interest is concerned.

In this sense, Missika (2006) states that politicians show their more personal face because they are aware that citizens are interested in knowing about their life. Aspects such as their family, their tastes and their anecdotes of the past make it possible to create affective ties with the audience and to leave out the ideological debates with the only intention of transforming these bonds into favorable votes.

«We are nothing more or nothing less than what we choose to reveal of ourselves,» says Frank Underwood›s character in House Card at one point in the series, and that is something that the Spanish presidential candidates are well aware of, being aware of the impact that television generates in its audiences, they understand that, as Quintus Tulio also pointed out, «people are carried away by appearance rather than by reality.»

6. REFERENCES

1. Alonso M (2017). En tu casa o en la mía: la entrevista como infoentretenimiento. Doxa, 23, 73-99.

2. Abejón P, Vinuesa L, Sánchez L (2013). Las mujeres políticas en España y su proyección en los medios de comunicación. Razón y Palabra, 82.

3. Álvarez JL, Pascual EM (2002). Las competencias de liderazgo de los presidentes de gobierno en España. Revista de Estudios Políticos, Nueva Época(116):267-280.

4. Badillo A, Marenghi P (2001). De la democracia mediática a la democracia electrónica. CIC. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 6, 39-61.

5. Barlovento (2016). El consumo TV. https://www.barloventocomunicacion.es/blog/144-informe-barlovento-el-consumo-tv.html.

6. Blanco JC (2015). Cinco debates cara a cara en once elecciones generales. http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2015/11/26/actualidad/1448533075_331524.htm l.

7. Berrocal Gonzalo S (2005). La información política en televisión: ¿apatía o interés entre los espectadores? Comunicar, Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación, 25 (2):1-7.

8. Berrocal S, Redondo M, Martín V, Campos E (2014). La presencia del infoentretenimiento en los canales generalistas de la TDT española. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 69, 85-103. doi:10.4185/RLCS-2014-1002.

9. Bobo M (2005). La función social de los medios y la situación actual de la televisión en España. Comunicar, 25, 2-12.

10. Carvajal A (2016). Pablo Iglesias renuncia a la mitad de los actos de campaña por la televisión. http://www.elmundo.es/espana/2016/06/03/57509c70468aeb7a0e8b45e3.html

11. Casetti F, Odin R (1997). Análisis de la televisión. Instrumentos, métodos y prácticas universitarias. Barcelona: Paidós.

12. Contreras JM (1990). Vida política y televisión. Madrid: Espasa.

13. Costa P (2008). Cómo ganar unas elecciones. Barcelona: Paidós.

14. Coupland D (1991). Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. London: Abacus.

15. EGM (2016). Entrega de resultados EGM 1ª ola 2016. http://www.aimc.es/Entrega-de-resultados-EGM-1%C2%AA-ola,1768.html.

16. Franco A (2011). La campaña de las Elecciones Generales de España en 2008 en el marco de la “americanización” de los procesos electorales. Tesis doctoral. Madrid: UCM.

17. Fernández Obregón FJ (2015).Comunicación política y televisión actual. Opción, 31(2):276-289.

18. Fernández Torres M (2005). La influencia de la televisión en los hábitos de consumo del telespectador: dictamen de las asociaciones de telespectadores. Comunicar, 25. http://www.revistacomunicar.com/verpdf.php?numero=25&articulo=25-2005-083

19. Gordillo I, Guarinos V, Checa A, Ramírez Alvarado MM, Jiménez-Varea J, López-Rodríguez FJ, De los Santos, F y Pérez-Gómez MA (2011). Hibridaciones de la hipertelevisión: información y entretenimiento en los modelos de infoentertaiment. Revista Comunicación, 9, 93-106.

20. Grabe M, Zhou S, Lang A, Bolls P (2002). Packaging Television News: The Effects of Tabloid Information Processing and Evaluative Responses. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44, 581-598. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4404_4

21. Kantarmedia (2015). Boletín de audiencias 2015. http://www.kantarmedia.com/es/soluciones/medicion-de-audiencias/television-y-video.

22. Laguna A (2011). Liderazgo y comunicación. La personalización de la política. Análisi, 43, 45-57.

23. Lluch P (2015). Podemos: nuevos marcos discursivos para tiempos de crisis. Redes sociales y liderazgo mediático. Dígitos, 1, 111-125.

24. López J (2011). De la democracia mediática a la democracia visiva. Acercamiento a la relación entre televisión y política. RUTA: Revista Universitària de Treballs Acadèmics, 3, 1-11.

25. Luzón V, Ferrer I (2008). Espectáculo informativo en noticias de sociedad: el caso de Madeleine McCann. Trípodos, 22, 137-148.

26. Martínez Pandiani G (2006). El impacto de la televisión en la Comunicación Política moderna. Signos, 25(1):69-88.

27. Mazzoleni G (2010). La comunicación política. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

28. Micovic M (2014). La comunicación y el discurso político en España y Serbia. Barcelona: UOC.

29. Muñoz-Alonso A, Rospir JI (1999). Democracia mediática y campañas electorales. Barcelona: Ariel.

30. Nieland J (2008). Politainment. En Donsbach W (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

31. Ntutumu F. (2015). La política pop, la caja tonta y el riesgo para la política democrática. https://ntutumu.wordpress.com/2015/08/29/la-politica-pop-la-caja-tonta-y-el-riesgo-para-politica-democratica/

32. Quevedo R, Portalés-Oliva M, Berrocal S (2016). El uso de la imagen en Twitter durante la campaña electoral municipal de 2015 en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 71, 85-107. doi:10.4185/RLCS-2016-1085.

33. Ramonet I (2002). La Post-Televisión: Multimedia, Internet y Globalización Económica. Barcelona: Icaria Editorial.

34 Sayre S, King C (2010). Entertetainment and Society. Influences, Impacts and Innovations. New York: Routledge.

35. Schultz D (2012). Politainment: The Ten Rules of Contemporary Politics: A Citizens’ Guide to Understanding Campaigns and Elections. USA: Amazon.

3 Thusu T (2007). News as enterainment. The rise of global infotainment. Londres: Sage.

37. Valencia A (2015). Políticas e imagen en una democracia de audiencia. Paradigma: Revista Universitaria de Cultura, 18, 27-29.

38. Vallespín F (2001). El futuro de la política. Madrid: Taurus.

39. Vilatod i Presas (2008). La imagen de las mujeres políticas en los medios de comunicación. En VVAA. Mujeres, política y medios de comunicación. Homenaje a Clara Campoamor. Sevilla: Fundación Audiovisual de Andalucía.

40. Wolton D (1995). Elogio del gran público. Una teoría crítica de la Televisión. Barcelona: Gedisa.

AUTHOR

Marián Alonso González

Marián Alonso González has a PhD in Communication from the University of Seville (2008) with a Doctoral Thesis on the technological change of ABC de Sevilla. She is a Communication Technician in ADIF Communication Department and Office of Presidency; she is a member of the Research, Analysis and Technique Group of the University of Seville where she develops her teaching career as an associate professor of the Faculty of Communication, giving lessons of Audiovisual Journalistic Writing.

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2676-0449

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alonso_Marian

https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=pTW9yp0AAAAJ&hl=es

ResearcherID: S-2855-2016

https://www.mendeley.com/profiles/marin-alonso-gonzlez/

ANNEX

7.1. Elections 2015. Programs to which the candidates came

7.2. Elections 2016. Programs to which the candidates came