doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.44.73-86

RESEARCH

THE COMMUNITY RADIO IN THE MEDIA FRAMEWORK OF THE CONGO

LA RADIO COMUNITARIA EN EL ENTRAMADO MEDIÁTICO DEL CONGO

A RÁDIO COMUNITÁRIA NA TRAMA MEDIÁTICA DO CONGO

Modeste Munimi Osung1

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

mmunimi@ucm.es

Recibido: 09/05/2017

Aceptado: 27/06/2017

Publicado: 15/11/2017

ABSTRACT

The article covers the third sector of communication and underlines the most outstanding features of the community radios in the Democratic Republic of Congo. From a brief panoramic description of the means of communication in this African country, it emphasizes the role of the third sector of communication to culminate with the role of the community radios. from the quantitative techniques, the findings of the investigations done demonstrate that the community radios act as valuable means of communication in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as they contribute to the formation and information, culture, literacy, social change and development of the people, mostly in the rural areas.

KEY WORDS: Communication, radio, community, associative, third sector, participation.

RESUMEN

El artículo aborda el tercer sector de la comunicación y resalta los rasgos más definitorios de las radios comunitarias en la República Democrática del Congo. Desde una breve descripción panorámica de los medios de comunicación en el país africano, se destaca el papel del tercer sector de la comunicación en ese país para culminar con el rol de las radios comunitarias. A partir de las técnicas cuantitativas, los resultados de las investigaciones realizadas demuestran que las radios comunitarias actúan como valiosos medios de comunicación en la República Democrática del Congo, ya que contribuyen en la formación e información, la cultura, la alfabetización, el cambio social y desarrollo de la población, sobre todo en las zonas rurales.

PALABRAS CLAVE: comunicación, radio, comunitario, asociativa, tercer sector, participación, colectividad.

RESUME

O Artigo aborda o terceiro setor da comunicação e ressalta os traços mais definidos das rádios comunitárias na República Democrática do Congo. Desde uma breve discrição panorâmica dos meios de comunicação do país africano, se destaca o papel do terceiro setor da comunicação neste país para culminar com a função das rádios comunitárias. A partir das técnicas quantitativas, os resultados das investigações realizadas mostram que as rádios comunitárias atuam como valiosos meios de comunicação na República Democrática do Congo, já que contribuem na formação e informação, na cultura, na alfabetização, nas mudanças sociais, e no desenvolvimento da população, sobre tudo nas zonas rurais.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Comunicação, Rádio, Comunitária, Associativa, Terceiro setor, Participação, Coletividade

How to cite this article

Munimi Osung, M. (2017). The community radio in the media framework of the Congo. [La radio comunitaria en el entramado mediático del Congo]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 44, 73-86. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.44.73-86

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/478

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the democratic opening in the 1990s, the media in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have been playing a vital role in public service, training and information, which has not always been addressed by dominant media public-governmental and private-commercial. In this context, this article tries to investigate the third sector of communication in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with emphasis on community radio.

This study is part of the first stage of our research for the doctoral thesis. This investigation led us to collect information from community radio stations in order to obtain the data that serve as the basis for a subsequent sample of interviews. The data thus collected are, on the one hand, from the FRPC (Fédération des Radios de proximité du Congo), an association to which the Congolese community radios belong. On the other hand, we have collected part of the information from the existing literature on community radios, although scarce.

The third sector of communication in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the result of an inefficient communication system in the interests of citizens that demands a response to that need. Thus, in order to understand it better and to highlight its particularities as alternative means to the state, private and commercial media, it seems opportune to tackle the media landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo first of all.

2. OVERVIEW OF THE MEDIA IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

2.1 Brief historical outline

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is located in central Africa, in the Great Lakes region. It is the third largest country in Africa, with an area of ??2,345,409 km2, an extension almost five times to Spain. It has a population close to 80 million inhabitants, estimated by the World Bank. With a per capita income of US $ 435, it is one of the poorest countries in the world, despite its many natural resources, such as cobalt, copper, cadmium, petroleum, diamond, gold, silver, zinc, magnesium, tin, germanium, uranium, radio, bauxite, iron, coal, coltan, etc. The country suffers serious humanitarian crises as a result of the wars that have affected it since 1990. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a unitary republic. The Constitution enacted in February 2006 defines it as a “rule of law, independent, sovereign, united and indivisible, democratic and secular.” However, according to Amnesty International’s report 2016/17 on the situation of human rights in the world, Congo is one of the countries where repeated violations of human rights occur. The African country occupies the position 375 on 472 in ranking.

Unesco has also presented a grim picture of press freedom in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Freedom in this African country has been restrained repeatedly during the Mobutu dictatorship and lately under the current President Joseph Kabila. According to the report of Reporters Without Borders for freedom of information, the country ranks 154 out of 180 in the world ranking of freedom of the press. According to the Congolese NGO JED, Journalistes en danger, during the last years, several journalists have been imprisoned and others murdered. The documented number of violations rises to 87 according to the NGO. In addition, several television channels and radio stations, both local and foreign, have been closed by the government.

2.2 Public media

The RTNC (Congolese National Radio Television) corporation is the only government-controlled media in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers less than 50% of the national territory, due to the technology and poor quality appliances they are still using.

The RTNC known as “La voix du Zaïre” during the Mobutu dictatorship was the main means of audiovisual communication, from the 1960s to 1990, the year of democratic and media openness. According to Yves Renard: “Until the 1990s, the Congolese are informed by the Voix du Zaïre, the great Tamas of Marshal President Mobutu. That Voix was the Mouvement populaire de la Revolucion (MPR), the single party, renamed Mourir pour rien by the inhabitants of Kinshasa who hoped that freedom of expression would come before irony over the country’s leaders. “After the fall of the dictator, the governments that have succeeded, that of Kabila Father and Kabila son, in force, continue to monopolize radio and public television as a political and ideological weapon. Therefore, we are dealing with an information and communication system, controlled, manipulated and at the service of power. For several decades, the Congo relied only on the state media. There were hardly any newspapers, radios, or private televisions, except for some magazines and radios of the Catholic Church. At the end of Mobutu’s regime a political pluralism began and a new journalistic era began. We attended the liberalization of the media that until now operated under the control of the State. The number of audiovisual and private and commercial newspapers is born and multiplied.

2.3 Private, commercial and religious media

The democratic opening in the Democratic Republic of the Congo brings with it a change in the private and commercial communication sector. Marie Soleil Frère calls it the beginning “of the extraordinary development of the Congolese media”. There is diversity of means of communication and the number of the latter grows drastically. There are currently 213 daily newspapers legally recognized and a dozen online in DR Congo. The city of Kinshasa has eight daily newspapers: Le Potentiel, Le Phare, L’Observateur, La Référence Plus, Le Palmarès, Forum des As, La Tempête des Tropiques and L’Avenir. There are two press agencies: ACP (Agence Congolaise de Presse) of the State and DIA (Agence de documentation et d’information africaine) of the Episcopal Conference of Congo (CENCO).

As for audiovisual media, there are more than 500 radio stations, of which 450 are community and associative, some 20 confessional radios, some 50 private radios, one UN humanitarian radio besides OKAPI radio, the only one a radio station covering the entire Congolese territory and 52 private and confessional television channels. In this way, the supply of media increases, at the same time, that the number of consumers of these means increases. It should be noted that 60% of these media are concentrated in the capital. While in large cities such as Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, television is the most frequent medium, in rural areas, radio is the favorite medium.

In spite of media pluralism, the commercial and confessional private media have not been able to become alternative references to profit logic, the product of their own partisan and commercial interests. According to Marie-Soleil Frère, the content of the information as well as the journalistic practices of most of these means remain partisan, serving some individuals and large companies.

Hence, the need to seek alternative communication in order to educate, inform and respond to the needs and problems of citizens.

2.4 The third sector of communication: Alternative means of communication

In order to better understand the scope of the communication we explore, we think it appropriate to explain the concept of the “third sector”. We rely on the definitions given by some authors such as: Donati (1997), Jerez and Revilla (1997), Bresser and Cunill (1998) and Montagut (2000).

For Bresser and Cunill, the concept of the third sector refers to a “third form of ownership between the private and the state, which does not pursue profit and its function is directed to the production of social services, not including control over them “On the other hand, Montagut defines it as” a set of entities or organizations that direct their activities, basically to the satisfaction of social needs, have no desire for profit, and are financed, in large part, by the public sector “ .

As for Jerez and Revilla (1997: 29), in designating the third sector as “the space of action between public authority and private companies: it refers to the development of forms of organization and action of private actors for public purposes.” Donate defines it as an “emerging social form that is born from the requirement to diversify the responses to specific social needs, which follow dynamics of decomposition and multiplication and, at the same time, require constant new relationships.” Of all these definitions, the following can be emphasized: the third sector is a non-profit organization or organization, which has a private, free and voluntary character as opposed to state or governmental. Therefore, it is proposed as an alternative to the state and commercial sectors.

However, applied to the field of communication, “the concept of the third sector refers to the media that emerge as initiatives of civil society to present in the public space all those topics of interest that are not represented or distorted presented by the media linked to private, commercial or state enterprises. Therefore, it is called alternative communication to the extent that it contributes to filling the void of state, private and commercial media. In addition, it offers a communicative alternative to the citizens, in which these are.

The concept of the third sector of communication in the Democratic Republic of the Congo explicitly emerges as a new reference associated with the finding of the inability of the mass media to be media of public interest. These are alternative means, which do not belong to any communicative enterprise, independent of any kind of power, other than the community to which it is directed. They are means that aspire to give voice to the voiceless. They have no commercial purpose. In DR Congo, these alternative media are classified as cultural radio stations, rural radios, peripheral radios, popular radios, free radios, humanitarian radios, community and associative radios, the internet, new information technologies and communication (NICTs), and social networks. As for the Internet and its components, that is, social networks, NICTs, only a smaller percentage of citizens have access to them. The Internet is still a luxury in that African country. Therefore, we will focus on community and associative radios, which we consider play an important role in the third sector of communication in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

3. COMMUNITY AND ASSOCIATIVE RADIOS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

The number of community and associative radios, also known as proximity radios, continues to increase in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. If in the nineties, there were a dozen radio stations, today there are 450 officially recognized. The reason for this growth, as shown by the Panos Institute in Paris, “is a response to the failure of public radio in general, which has long been the product of the city and of established power ... In contrast, radios of proximity are close to the population and serve as a space of expression for the deep aspirations of the community.” On the other hand, 82 per cent of the population of the Congo estimated at 80 million live in rural areas and have no access to radio and public television. “On the other hand, it is the community media that carry out the mission of social liaison and fulfill the function of intermediation.”

3.1 Description of Community Radios in the DRC

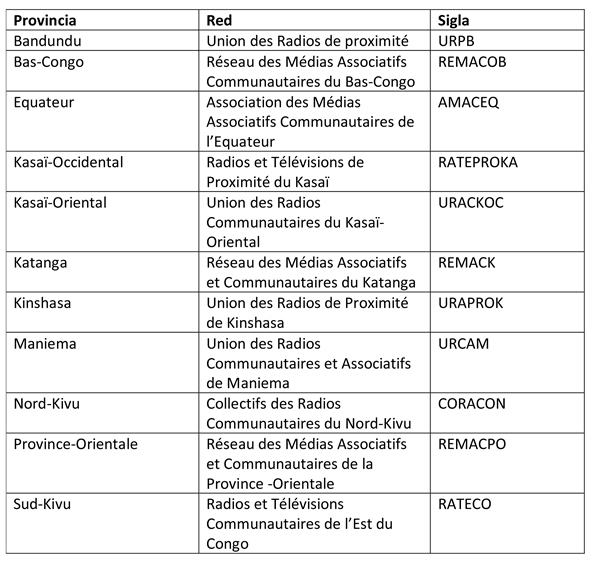

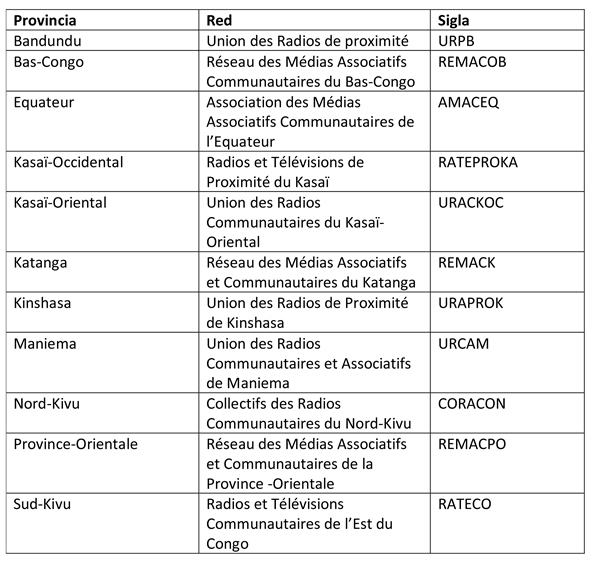

Community and associative radios, also known as “proximity” radios, are organized in provincial networks, on a network by province basis and in a national network, the FRPC (Fédération des Radios de Proximité du Congo), which collaborates closely with AMARC, an international non-governmental organization serving the community radio movement, which brings together about 4,000 members and partners in more than 110 countries. The aim of AMARC is to support and contribute to the development of community and participatory radio in accordance with the principles of solidarity and international cooperation. At the International Council of AMARC are represented all the continents.

“Community radio is a constant doing that relates to people, their life, their history, their dreams, their hopes and their expression.” Community radio stations in the Congo call them “proximity” radios because they are rooted in the community. Rigobert Malalako, national executive secretary of the FRPC, speaks of the establishment of these means and states the following:

“More than a decade ago, alongside public and private (commercial) media, another voice was put up,” which supposedly must defend the interests of citizens. “The one who informs, who helps solve one and a thousand problems of the life of the citizens, a space where the voices of all are heard without discrimination, which makes education a priority, are alternative and close to the realities of our populations for their proximity information. radios of community and proximity, radios of proximity, overcome language barriers, distances, communication difficulties, reach men where they are as a factor of development.

3.2 Names of Community Radios

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, community radios are known as associative, community radio and proximity radios. However, as Marie-Soleil Frère points out, “most of these broadcasters, even though they call them” community “or” associative “, are not actually in their internal organization either in their programs or in their mode of financing. “

In fact, most community radios belong to individuals, NGOs, or religious denominations, so the community has no responsibility for them. Others subsist thanks to the funding of some politicians and institutions. They also serve as a support for the propaganda of these politicians. Some of the radios admit advertising to survive.

3.3 Linking the radio to the local community

Community radio belongs to a community. It is a station for the community, the community and the community. In this sense, the community serves as a frame of reference and “radio is administered in a representative and democratic manner by that community.” However, the concept community can be understood in different ways. For Hollander and James Stappers & Nicholas Jankowski, community is understood not only as a geographic setting, but primarily as a social setting. AMARC defines it as “a group of people or a community that shares common characteristics or interests.” But the case of the Democratic Republic, according to the information we have been able to obtain, is ambiguous. The criteria that define it are flexible and, therefore, inaccurate. Most stations are linked to the community for geographical reasons, especially in rural areas where it does not matter who owns it. In many cases, the radio is first created with the intention of doing something for the community, in this respect, it can be an individual or an association, and then links it to the community. In this case, the owner still remains the owner, partially involving the community, which has no control over the property.

However, community radio stations in the Republic of Congo call them colloquially “la case au milieu du village” (the house in the middle of the village). They play an important role in the dissemination of information, from minor to major importance, such as messages and announcements from the community. The announcements about deaths, about family reunions or important meetings, in short, about different events that affect the daily life of the people. Therefore, the station also plays the role of telephone.

Marie-Soleil Frère states, “Each radio has dozens of examples of situations where a radio communiqué made it possible to find objects or lost cattle, launch a vaccination campaign, mobilize the population to participate in collective efforts to combat erosion or afforestation, announcements of a death or an important meeting. “

3.4 Community involvement in radio

Citizen access and participation in the radio station is the exclusive feature of community radio. The fact that the audience is present in the radio programs is not new. In fact, throughout its history, the radio has been able to offer audiences the possibility to express themselves on the air. Now, although the listeners have access to the stations, they do not feel, however, owners of them. When the direction of the radio is in the hands of a few (companies, power, etc.), this hampers the free and authentic participation of the audiences in the radio spaces.

There, it is where community radios are distinguished merely from traditional radios. One of the specific ways in which the community participates in these stations is the «club radios», which are platforms where listeners of the radio station meet together to listen to the radio programs and then get their criticisms and suggestions. Community radio Maendeleo in Bakuvu, for example, has more than 100 «club radios» that are in contact and regularly exchange content with the broadcaster. 3.5 Partnership with national and international organizations

Community radios in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are members of provincial associations, according to the province to which they belong and the FRPC (Fédération des Radios de Proximité du Congo), therefore members of AMARC. Some of them are linked to other national or international organizations or radio stations, from which they receive materials, technical support or some subsidies. These are some of these organizations: l’INSTITUT PANOS PARIS (a French NGO that supports the training of professionals in some community radio stations); GRET (Research and Technological Exchange Group, a French NGO specialized in economic development); FONDATION HIRONDELLE (an NGO based in Lausane in Switzerland, specialized in creating radios in conflict zones); SEARCH FOR COMMON GROUND (an international NGO based in the United States supports community radios in the peace process by providing credible, accurate and accountable information); La BENEVOLENCIJA (a Dutch NGO whose mission is to promote peace and reconciliation through radio programs in conflict zones); RADIO NETHERLANDS TRAINING CENTER (it is an international training structure within Dutch radio through its INFORMORAC program, which supports community radios); RADIO FRANCE INTERNATIONALE (RFI radio supports some community radio projects such as training journalists and technical support with equipment), UNESCO, etc.

3.6 The content of the programs

Elsa Moreno ratifies, part of the identity of the station is reflected in the selection of its contents. Through its program grid, community radio is understood as an actor and interlocutor of the community and plays its role as spokesperson and community.

The programming of community radio stations in the Republic of Congo is diversified according to the needs of the target audience. Each issue throughout the day aims at a specific audience and aims to respond to a specific need of the community. The variety of programs that exist in these radios range from microprograms, classic programs such as local and national information, social gatherings, interviews, debates, to the radio announcements that allow to cover different types of topics, where you can find some more specific and localized, as customs and traditions, rural animation in different dialects, know how to live, agriculture, small commerce, etc. Others are more general and deal with the problem of family, youth, coexistence between tribes, ethnicities and peoples, education, etc.

In general, the programs cover the different topics of daily life of the population, elementary issues such as education, hygiene standards, to complex issues such as family planning, interpretation of laws, etc. All these programs aim to respond to the needs of the community.

The programs are generally broadcast in the national languages, according to the province in which the station is located. These are the 4 national languages: Kikongo, Lingala, Swahili and Thsiluba. Some specific programs, such as rural animation, are broadcast in the different dialects of the community. Other programs, although very few, are also broadcast in French, the official language of the country. The language used in the programs is simple and understandable for most of the population. Popular expressions are widely used.

3.7 Legislation on community radios

Article 24 of the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, approved by referendum in December 2005, guarantees freedom of opinion and expression and the freedom to receive and disseminate information through the media. However, according to Marie-Soleil Frère, “the legal framework in which the Congolese media is evolving is essentially circumscribed by two texts: the law of June 22, 1996, setting the modalities for the occupation of press freedom in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the law provision of 2 April 1981, which defines the status of journalists working in DRC. “Despite the significant number of community radio stations (450) and despite their impact on people , the current law does not mention or recognize community and associative radios in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Through a memorandum addressed to the Ministry of the Media and to the President of the Higher Council of Audiovisual and Communication (CSAC), the Federation of Radios of Proximity of the Congo (FRPC) calls for the legal recognition of radio stations and the Community. Therefore, “the FRPC calls for the modification of legal and normative texts by integrating specific provisions concerning associative and community radios, the distinction between them and the private and commercial media.” In addition, the Federation considers that the public power should rather encourage the emergence of this new type of media taking into account its specificity and give it a particular legal regime adapted to its essence.

3.8 Use of 2.0 technologies

Of the 450 community radios that are the subject of our studies, only 7 have internet connection, also have websites and are connected to social networks. According to Marie-Soleil Frère, “The teams are old and handcrafted. Most radios do not have numerical equipment and do not have the opportunity to use the resources offered by NICTs. “

3.9 The staff

The precariousness of the professionals is remarkable. Community radio staff suffer from a lack of training globally. However, there are a number of institutions, such as UNICEF and UNESCO, and international broadcasters such as RFI, which seek to ensure the training of professionals in these media and who may be the seeds, in some cases, for the development of journalism as an independent profession and with a clear sense of mission in community radio.

4. CONCLUSION

The present research has allowed, on the one hand, to advance in the empirical knowledge of community radios in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite the enormous difficulties and shortcomings of the majority of community radios in Congo, difficulties and shortcomings attributed mainly to the lack of clear legislation of these stations by the government, the lack of training of professionals, the limited provision of equipment and financial resources, it is worth noting the important work being carried out by these broadcasters in the Congo. After the UN community radio, Okapi radio, which covers the entire Congolese territory, community radios are the media present in all corners of the Congolese territory that reach the most remote places of the country.

On the other hand, this study shows differences in the understanding of the concept community radio taking into account the practices of most of these stations. However, we consider them as limitations that could be supplemented, in part, by strengthening synergies with the training of media professionals and with a law that clearly covers and defines the functions of community radio stations.

Finally, we believe that the present study demonstrates the enormous potential of community radio as a means of the third sector of communication in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. We will agree with Marie-Soleil Frère that community radios are “unavoidable actors that contribute to the strengthening of citizenship. To this end, they are often the privileged partners in development cooperation and funding providers, who support them with equipment, professional training and financial support. “

5. REFERENCES

1. Annuaire des radios communitaires de la République Démocratique du Congo (2012).

2. Asociación Mundial de Radios Comunitarias. http://www2.amarc.org/?q=es/node/131

3. Boulc´h S (2003). Radios Communautaires en Afrique de l’Ouest. Guide à l’intention des ONG et des bailleurs de fonds. Bruxelles.

4. Domingo Ramírez J (2015). La radio comunitaria en el sur de Chile. Análisis del discurso de sus actores. Comunicación y Medios, 31, 66-87.

5. Entrevistas a los directivos de la Federación de radios comunitarias de la República Democrática del Congo (FRPC) (2016).

6. Frère MS (2008). Le paysage médiatique congolais. État de lieux, enjeux et défis. Paris: Éditions Karthala.

7. Frère MS (2005). République Démocratique du Congo: Les médias en transition. Médias, journalistes et espace public. París: Karthala. 49-65.

8. Hollander E, Stappers J, Jankowski N (2000). Community media and community communication. En Jankowski NW (ed.). Community media in the information age. Perspectives and prospects. Cresskill New York: Hampton Press. 19-30.

9. Journaliste en Danger (2016). Rapport 2016, En attendant les élections… La pire saison pour la presse en RD Congo. http://jed-afrique.org/

10. La reconnaissance légale des radios communautaires du Congo. Memorandum adressé au Ministère des Médias et au président du Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel et de la Communication (CSAC) par la FRPC (20179). http://www.frpcmedias.net

11. Moreno E (2005). Las “radios” y los modelos de programación radiofónica. Comunicación y Sociedad, XVII(1):1-52.

12. Renard Y (2008). Des médias entre proliferation anarchique, impunité et pauvreté : le défi de la reconstruction du champ médiatique en RDC. Afrique contemporaine, 227, 135- 152.

13. Reporters Sans Frontières (2017). Classement mondial de la liberté de la presse 2017. https://rsf.org/fr/classement

14. Rodríguez López J (2005). Tercer Sector: Una aproximación al debate sobre el término. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, XI(3):464-474.

Anexo 1

Fuente: Annuaire des radios communitaires de la République Démocratique du Congo, Édition 2012. P. 10

AUTHOR

Modeste Munimi Osung

Degree in Journalism from the University Center Villanueva, Madrid, assigned to the Universidad Complutense de Madrid; Bachelor of Ecclesiastical Studies from Catholic University of Eastern Africa (CUEA), Nairobi-kenya; Master in Social Communication. Communication, Social Change and Development by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid; Doctorate student in Audiovisual Communication, Advertising and Public Relations at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. He has participated in the 9th International Congress on Ethics and Information Law (Mission of journalism in developing countries: the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The ethical and social responsibility of informative companies (COSO Foundation).