doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.48.65-86

RESEARCH

THE PRO HOMINE PRINCIPLE AS A BASIS FOR THE LEGISLATION OF GENDER PROTECTION MEASURES

EL PRINCIPIO PRO HOMINE COMO BASE PARA LA LEGISLACIÓN DE MEDIDAS DE PROTECCIÓN DE GÉNERO

O PRINCÍPIO PRO HOMINE COMO BASE PARA A LEGISLAÇÃO DE MEDIDAS DE PROTEÇÃO DE GÊNERO

Laura V. Córdova P.1, Víctor H. Córdova A.1, Héctor F. Gómez A.1

1Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador Sede Ambato. Ecuador.

ABSTRACT

The protection measures are those attitudes and decisions that the State takes into account through its various public institutions, in order to make effective the care and protection of the victim of the aggression, with respect to the aggression itself and its aggressor; they are mechanisms that seek to provide support and protection to the victims of the aggressions and prevent their continuation. The present research work seeks to establish the current situation regarding the granting of protection measures, as well as the application of the Pro Homine principle at the moment of issuing them, as a philosophical basis for the elimination of vulnerability in gender. This work shows definitions and application of the principle as well as conclusions and recommendations in the decision making under its elucidation.

KEY WORDS: woman, violence, protective measures, principle Pro Homine

RESUMEN

Las medidas de protección son aquellas actitudes y decisiones que toma en cuenta el Estado a través de sus diversas instituciones públicas, a fin de hacer efectivo el cuidado y protección de la víctima de la agresión, con respecto a la agresión misma y a su agresor; son mecanismos que buscan brindar apoyo y protección a las víctimas de las agresiones e impedir la continuación de estas. El presente trabajo de investigación, busca establecer la situación actual referente al otorgamiento de medidas de protección, así como la aplicación del principio Pro Homine al momento de la emisión de las mismas, como fundamento filosófico de la eliminación de la vulnerabilidad en género. Este trabajo muestra definiciones y aplicación del principio además de conclusiones y recomendaciones en la toma de decisiones bajo su dilucidación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: mujer, violencia, medidas de protección, principio Pro Homine

RESUME

As medidas de proteção são aquelas atitudes e decisões que toma em conta o Estado através de suas diversas instituições públicas, afim de fazer efetivo o cuidado e proteção das vítimas de agressão, em relação a agressão e seu agressor; são mecanismos que buscam brindar apoio e proteção as vítimas das agressões e impedir a continuação das mesmas. O presente trabalho de investigação, busca estabelecer a situação atual referente ao consentimento de medidas de proteção, assim como a aplicação do princípio Pro Homine ao momento da emissão das mesmas, como fundamento filosófico da eliminação da vulnerabilidade em gênero. Este trabalho mostra definições e aplicação do princípio ademais de conclusões e recomendações na toma de decisões em base a sua elucidação.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: mulher, violência, medidas de proteção, princípio Pro Homine

Correspondence: Laura V. Córdova P.: Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador Sede Ambato. Ecuador.

laura.cordova@uasb.edu.ec

Víctor H. Córdova A.: Technical University of Ambato. Ecuador. victorhcordova@uta.edu.ec

Héctor F. Gómez A.: Technical University of Ambato. Ecuador.

hf.gomez@uta.edu.ec

Received: 21/03/2017

Accepted: 09/01/2019

Published: 15/03/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

According to what Montufar (1994) states: “Violence against women is a form of action as old as the most remote historical memory, and probably has existed since the first babbling of sociability” (p. 15), with what is established it is clear that violence against women is a performance within society, which has always been given, establishing a status of superiority of man over women in society, both in public and private aspects. (Ojeda, 2010) she says, “while the man is obliged by society to work in the public sphere, the woman had the “moral” responsibility to stay herself in the private sphere, to work in household chores and to raise children” (p. 88), it is clear that this conception has been maintained from generation to generation, there has been a system of marked roles given for each gender, which has been inculcated in education that establishes models to follow both for women, in their role of caring the home and the children, that is to say that their performance was in the private sphere of the home. The problem of violence against women and other members of the family is born of anthropological issues, not merely social or cultural issues, since from ancient times these roles have been established for each sex, both male and female, from prehistoric times in which the man had to go out to search for food and the woman to stay in the care of the home and the family, all this has been a guideline so that each culture has established this behavior as a mandatory parameter within society. With the entry into force of the new (Organic Comprehensive Criminal Code, Official Gazette: No. 180, 2014), physical as well as psychological violence against women and members of the family was established as a crime of public action contemplated in article 155 of the aforementioned Code. It is a change within the legal system, which has presented procedural difficulties in terms of the correct and effective application of protection measures for the victims of these crimes. With the previous Penal Code, this type of aggressions was processed within the Unit of Violence against Women and the Family, an institution where, when receiving complaints regarding violence against women, protection measures were immediately issued for the victim, with the aim of preserving its integrity and protecting it from future aggressions.

Within the Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador, the principles of the exercise of rights are established, specifying that in matters of constitutional rights and guarantees, public, administrative or judicial servants must apply the norm. This is in direct agreement with what is established by the precept of the Pro Homine principle itself, which requires that the legal interpretation seek the greatest benefit for the person, that is, that the broader norm should be applied to extensive interpretation when it comes to protected rights, with priority if it implies the benefit to the integrity, security and protection of the victim. It is based on the foregoing that the effectiveness of the judicial proceedings regarding crimes of violence against women and members of the family nucleus is questioned, specifically in the timely granting of protection measures, which are not established immediately and can even be denied if there are no elements that motivate the provision of the same, which leaves the victims of this type of crime in a state of insecurity and helplessness, increasing the risk of being subject to aggression again or in turn be victim of a more serious crime. This problem arises when a complaint for assault against the woman or members of the family, the prosecutor must ask the judge to grant the protection measures which must have valid grounds to grant them, which makes that the measures of protection are not immediate. This is originated in the regulations which determine the procedure to be taken within cases of violence against women or members of the family nucleus, which establishes that the granting of protective measures must be motivated, both in the request of the prosecutor and in the granting of the Judge.

This work constitutes a research project regarding the granting of protection measures in the crimes of violence against women and members of the family nucleus, because within the Ecuadorian legislation there has been a change to the procedure to be followed in these cases, since that is currently classified as a crime, therefore it is a process that must be processed by the Government Attorney Office and difers from the procedure followed by the previous law, specifically with regard to the granting of protection measures. The purpose of this investigation is to know how this type of delay affects the victims of this type of violence, as well as to know how it endangers their integrity and above all to establish clearly what are the protection measures applicable to these cases and which way these could be more effective in terms of their granting. To make our proposal clear, in Chapter I, Theoretical Foundations, we find the state of the art, which is a review of the previous research in relation to the subject; followed by the description of the problem posed, which is the exposition of the causes and consequences of the investigation; at the same time the exposition of the basic questions that help to understand the problem; later there are both general and specific objectives, which are the goals to be achieved within the investigation; the study question is also indicated, which is the result of the investigation. We also have the signaling of variables, since a cause-effect relationship intervenes; then the network of conceptual inclusions and finally the theoretical foundations, where the topics and sub-themes related to research are developed.

In Chapter II, Methodology, the research methodology is described, identifying the approach, the modality and types of research used in the development of the work, the sources of research and the techniques and instruments used, in order to achieve the objectives stated above. In Chapter III, Results, we find the analysis and interpretation of the results, establishing a detailed analysis of what we receive as a derivation and as responses to the application of the research instruments. Finally, Conclusions and Recommendations, which emerged from the present research project strengthening the importance of it.

In terms of this (Chávez, 2012) it establishes that this type of violence cannot be addressed as an individual problem or an isolated act, considering the particular circumstances between the aggressor and the victim but as a social problem that anchors its roots in the social relations of inequality. Within the investigation of (Quiña, 2010) developed in the canton Ambato establishes that a large percentage of people know the definition of intrafamily violence but almost the same percentage of people do not know about the protection measures against these aggressions, as well as those who have benefited from protection measures have not used them, what has produced the recidivism of violence. This is in direct agreement with what is established by the research carried out in Canton Ambato de (Quinatoa, 2012), which concludes that there is a lack of knowledge of the measures of protection by the population, which prevents a proper exercise of the administration of justice, leading to new cases of intrafamily violence.

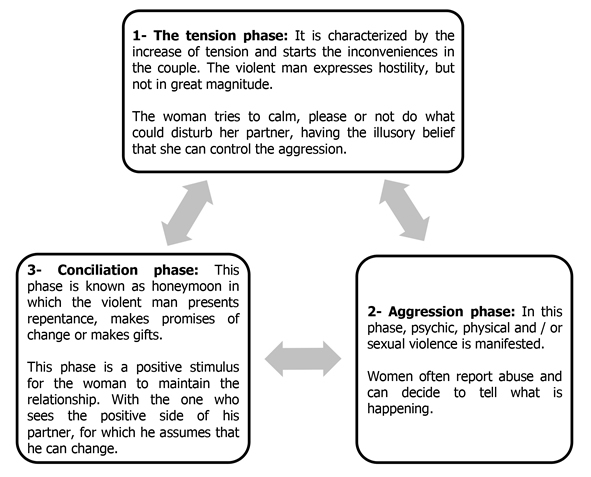

It is clear that the violence that exists within a home is a conscious act that manifests from one member to another, always these parameters of inequality have been established within the guidelines of society, indicating that there will always be a figure of superiority and in turn the other members must maintain a position of subordination, this hierarchy is defined as previously explained, by factors of gender and age. In order to have a clearer explanation of how the aggressor operates on the victims, it is important to cite what (Walker, 1979) establishes, this author says that when there is a relationship of violence, the woman is within a cycle which It consists of three phases: 1) the tension accumulation phase, 2) the violent exploitation phase and 3) the honeymoon phase. Each of them has specific characteristics that mark a violent relationship.

Source: Self made.

Graph 1. Cycle of violence.

This cycle of violence clearly explains how violence complies with a cycle which, over time, presents certain changes, the aggression phase is repeated more often or is maintained all the time between tension and aggression, barely goes through the conciliation phase, which implies a higher level of violence. It is important to point out that during two phases of this cycle the violated person endures such violence with the expectation of changing their partner or in turn when showing repentance and a good attitude, it preventing the victim from having a clear decision to stop the violence.

As we have been able to indicate in the cycle of violence, this is taken as a normal dynamic, in which in most cases who is the victim of the aggressions, feels responsibility that they have occurred and feels that they must take an attitude of submission for not causing a future aggression.

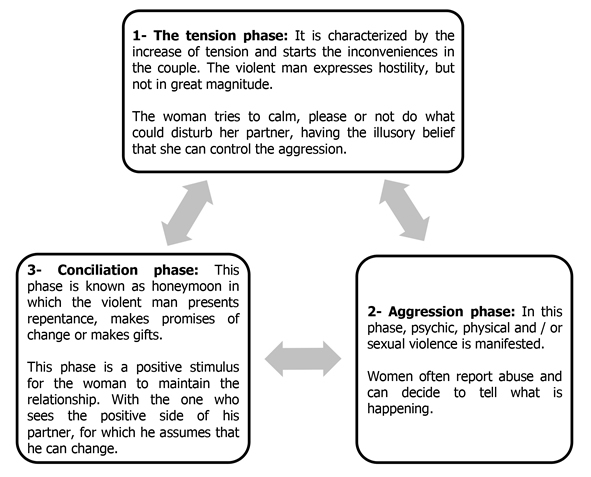

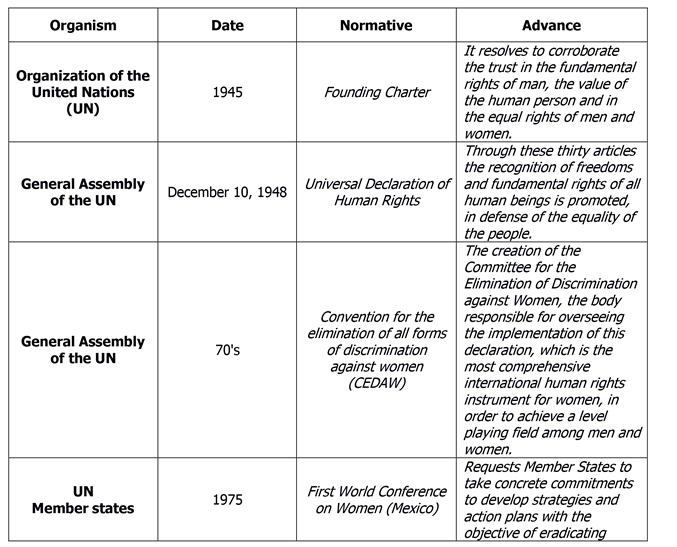

When talking about gender as well as intrafamily violence, it is clear that it is a problem of importance dealt with at a global level, which has generated a general awareness, which through collective efforts has been qualified as a collective interest. Thanks to this awareness process which has been born from some movements of struggle and defense of rights, recognition has been achieved within the international community, these efforts have been reflected in international treaties and conventions that today have constitutional status and even supraconstitutional.

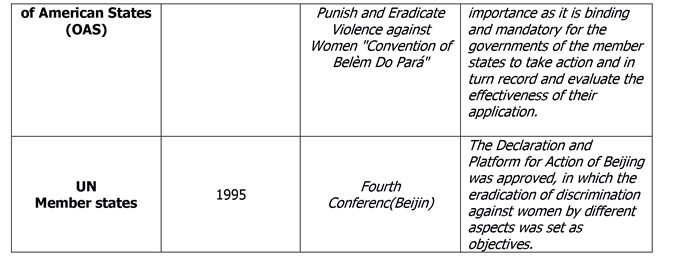

The evolution of human rights in general and specifically in relation to the subject of gender and intrafamily violence can be seen in the following table:

Table 1. Evolution of rights in gender and intrafamily violence at the international level.

Source: Self made.

1.1. Gender and intrafamily violence from a national perspective

As it has been possible to establish, gender violence is a global problem, which is not alien to the reality of our country, which as we know has also been susceptible to changes and developments in terms of rights and protection thereof, for which It is important to establish the most relevant facts that have been developed in the country throughout history regarding the central theme of this research.

To be able to have a starting point we can establish the beginning of the government of Jaime Roldós Aguilera, in this mandate more importance was given to the issue of rights violation, but still not focused on gender violence.

One of the most notorious changes could be seen from the 80s, taking into account the difference between genders, awareness is born in turn about the issue of violence against women, by certain groups.

Already in the 90s, the social pressure exerted through feminist organizations gave rise to the establishment of projects regarding public policies with a focus on the elimination of all types of violence, whether against women or intrafamily, from this point they have initiated facts of greater relevance as far as the progress in this subject, of which we can establish some:

The first agency pro women to be created was the National Women’s Directorate (DINAMU), which was part of the Ministry of Social Welfare, which became the National Women’s Council (CONAMU), since the year 1997, as stated in the Official Registry No. 128, this entity is created from the commitment agreed at the Conference of the Women in Beijing, this entity had the purpose of promoting public policies for the benefit of gender equality and respect for the rights of women, in this time also other organizations were born which established the first free legal offices to take gender and intrafamily violence specifically. It is important to point out that gender and intrafamily violence was not considered a problem of a public nature, which, being only a matter of private profile, became more difficult for their treatment and the safety of the victims.

In 1994, the creation of one of the most relevant institutions in terms of gender and intrafamily violence was started, which are the Women’s and Family Commisariats, but its field of action was limited since they lacked a legal foundation for the protection of justice in matters of gender and intrafamily violence, so that there were no effective legal actions that could be ordered.

Already by the year 1995, the first law to be able to judge crimes of gender and intrafamily violence is approved, which was approved on December 11, in the Official Registry No. 839, the Law Against Violence against Women and the Family, also known as Law 103, the same law that established intrafamily violence as an infraction, thus providing for sanctions and protection mechanisms in favor of victims. This law was enforced through the Women’s Commissariats, previously established.

After three years there is another important advance within the Political Constitution of Ecuador (1998), within which states that the State is obliged to take measures to prevent, eliminate and penalize violence against children, adolescents, women and people of the third age.

In 2008, with the enactment of the current Constitution of the Republic, recognition is given to personal integrity, in all aspects, both public and private. Therefore, in the case of intrafamily and gender-based violence, priority and specialized attention is guaranteed both to the victim and to the judgment, in virtue of which the State adopts the necessary measures to prevent, eliminate and penalize all forms of violence, especially the one against women and the family nucleus. For the execution of all the exposed within the Organic Code of the Judicial Function (2009), it is arranged that the jurisdictional authority will be exercised by the judges in specialized form, according to the different areas of the competition; At the same time, it is indicated that in cases of gender and intrafamily violence, mediation or arbitration is not possible and the Courts for Violence against Women and the Family are created.

For the year 2013, the judges specialized in the matter of violence were just given possession, which started the work of the Judicial Units against Violence against Women or Members of the Family Nucleus.

In 2014, with the entry into force of the Comprehensive Criminal Organic Code, in Official Gazette No. 180, the topic of gender and intrafamily violence takes a new direction, since violence is no longer considered only as a contravention, for be classified as a crime, therefore the body responsible for its procedure becomes the Government Attorney Office, with trial in Criminal Court.

As we have seen, gender and intrafamily violence has been a problem of transcendence within our country, which has had a somewhat late evolution, but which in recent years has had many projects and efforts to change its situation.

1.2. Gender and intrafamily violence from a provincial perspect

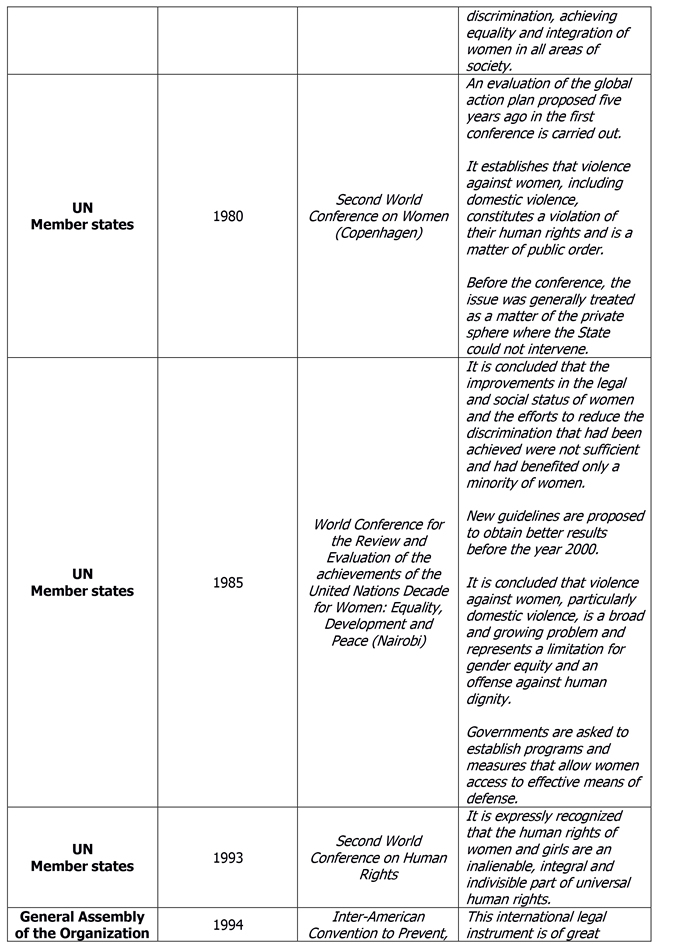

When talking about the problem of gender and intrafamily violence, it is important to highlight the current situation that frames our province. Therefore, the situation of the same can be established by means of graphs.

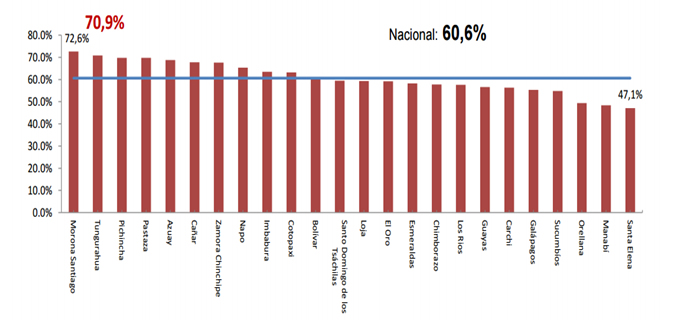

The National Institute of Statistics and Census - INEC (2011), established the First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women - Tungurahua, which was a response to the need for information about our environment focused solely on the issue of gender and intrafamily violence, which gives off the following information:

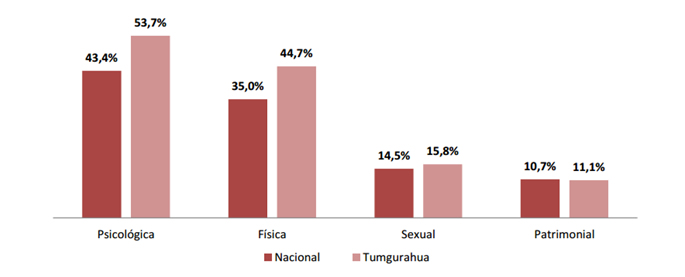

Source: First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women – Tungurahua.

Graph 2. Women who have experienced some type of violence - By province

According to the survey conducted, Tungurahua is the second province that registers greater violence against women with 70.9% compared to 60.6% of women nationwide. Considering all types of violence: physical, psychological, sexual, patrimonial.

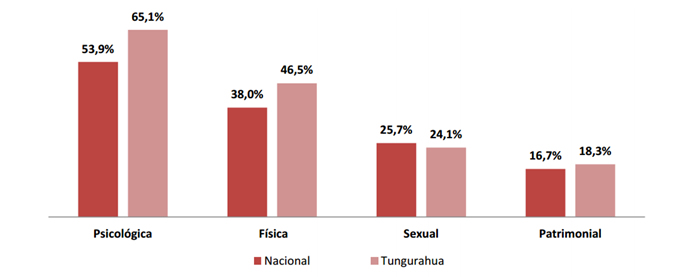

Source: First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women – Tungurahua.

Graph 3. Women who have experienced psychological, physical, sexual and patrimonial violence - General

According to the Tungurahua survey, psychological violence is the most recurrent form of gender violence with 65.1%, even at the national level, followed by physical, sexual and, finally, patrimonial violence.

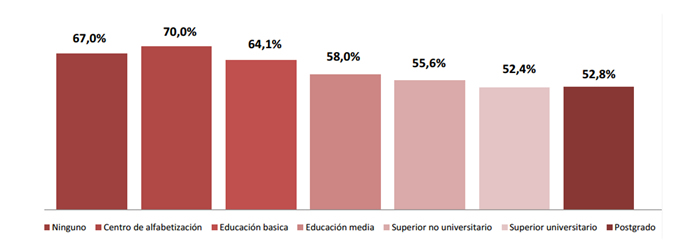

Source: First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women - Tungurahua.

Graph 4. Women who have experienced some type of gender violence by level of education.

It can be established that at all levels of education, gender violence exceeds 50%, but in women with less education, violence reaches 70%, which indicates that the problem of violence affects not only a specific group but it is still governed only by people with little education, but on the contrary, it affects anyone without counting their level of academic preparation.

Source: First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women - Tungurahua.

Graph 5. Women who have experienced physical, psychological, sexual and patrimonial violence by their partner or former partners.

53.7% of women in Tungurahua have experienced psychological violence in their relationships, that is, more than half, in turn, the index of physical violence in the province is very high, which almost reaches half of the women of the province.

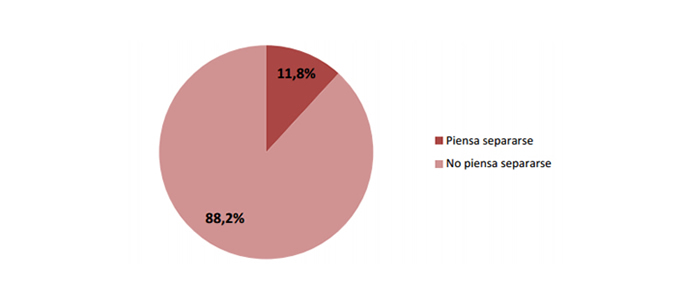

Source: First National Survey of Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women - Tungurahua.

Graph 6. Women who have suffered gender violence, according to their decision regarding their partner.

Contrary to what one would think, most women who have suffered or suffer some type of violence, do not think about becoming separated, instead only a minimum percentage considers it.

According to what is established, gender and intrafamily violence in a problem of great impact in society and mostly within our province, it is clear that culture and customs, have established that in general violence is normal within the development of a couple or a family, which prevents this problem from ending.

1.3. Fundamental parameters for legislation and prosecution on violence against women

The characterization of violence establishes an important advance in terms of the guarantee of rights, which demonstrates the commitment of the States and the international community to eradicate this problem. According to what it indicates Fries & Hurtado:

There was not much debate about where to lodge the treatment of violence legally, since any other jurisdiction that was not the criminal one tended to devalue gender violence against the treatment of other violence such as those committed by a stranger and mainly referred to homicide, injuries and sexual crimes. It also assumed the need for it to be a criminal type (in the code or in a special law) and not subsumed in the existing criminal types that had not historically collected this problem. (Fries & Hurtado, 2010, p. 16).

When talking about the characterization of violence, it should be framed within a criminal type, since the violation of rights that this implied is at the same level as other crimes that violate people’s fundamental rights. In turn, its classification should be particular and not fitting into other types of crime regulated previously, since its particular classification, even in creating a special law, demonstrates the importance given to this problem.

2. METHODOLOGY

The present investigation used the paradigm (qualitative quantitative), the same as the bibliographic-documentary modality and the field modality, in the documentary-bibliographic modality through the use of academic articles, books, doctrine, journals, theses, legislations , etc. , which were the source of help for the collection of information on the subject of research, in addition the information received was applied on the basis of valid and reliable documents in the form of primary information, thanks to which we were able to determine which protection measures are applied to victims of violence against women or members of the family nucleus and, in turn, to know about the Pro Homine Principle.

Referring to the field modality we can determine that we went as researchers to different institutions in order to obtain information about the subject of research, this has allowed us to assess the real situation of the problem posed.

2.1. General Method

The general method applied to the investigation was the Inductive, because it allowed to analyze a series of facts and events of a particular nature to arrive at generalities that serve as a reference in the investigation; with which it is possible to establish a general conclusion that affects the generality of cases.

2.2. Specific Method

The specific method that has been used in this present investigation has been the analytical method, since the research has been decomposed in all its elements.

2.3. Information Collection Techniques and Instruments

Within the technique used in this investigation, the gathering of information on the subject was carried out in the Tungurahua Provincial Government Attorney Office; thus, an interview was also conducted to the First Instance Judges of the Criminal Judicial Unit based in Canton Ambato.

The fundamental technique that was applied is the structured interview to capture the information of experts and people related to the research to be able to capture their criteria and points of view related to the subject.

3. EXPERIMENTATION

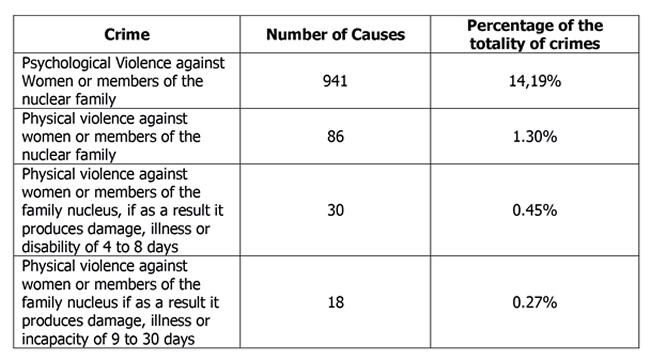

In order to comply with the first objective of the investigation, corresponding to diagnose the situation of the protection measures in the crimes of violence against women and members of the family, the information was collected in the Provincial Government Attorney Office of Tungurahua where indicators were taken related to the subject, which shows the following results:

Table 2. Percentage of complaints related to crimes of violence against women or members of the family in the Tungurahua Government Attorney Office, January- June 2015.

Source: Tungurahua Government Attorney Office Data.

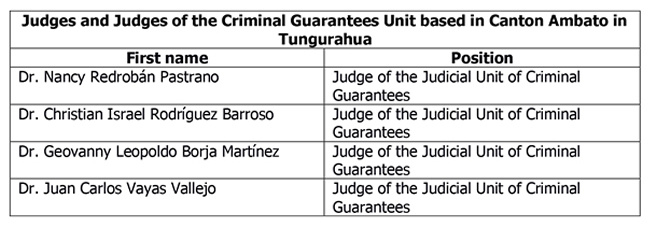

To comply with the second and fourth objectives of the investigation, which are to establish the protection measures applicable to victims of crimes of violence against women or members of the family nucleus and to compare the measures for the protection of victims of crimes of violence against women or members of the family nucleus in relation to the Pro Homine Constitutional Principle, interviews were conducted to Judges of the Criminal Guarantees Unit based in Canton Ambato in Tungurahua.

Table 3. Judges interviewed.

Source: Judicial Unit of Criminal Guarantees.

4. ANALYSIS OF INTERVIEWS AND INFORMATION GATHERING

4.1 Gathering information

Within the information that was granted by Dr. Adelaida Palate, of the totality of cases that are processed within the Provincial Government Attorney Office of Tungurahua, the crime that is processed in a greater percentage within this institution is that of Psychological Violence against the woman or members of the family nucleus, in comparison with this one there is no index as high as this of crimes of physical violence against this specific group, but within both crimes there is a need to issue protection measures, which is not done immediately or no requirement is given to them.

4.2 Judges interview

4.2.1. Judge 1

During the interview with the judge, she was able to state that the protection measure most applied to victims of violence against women or members of the family is the extension of a ticket for assistance.

At the same time regarding the knowledge of what the Pro Homine Constitutional Principle implies, it established that this principle is a form of legal interpretation which must seek the benefit for the human being, in concrete application to the crime of violence against women or members of the family nucleus would speak of the interpretation of the rule in favor of the victims of these crimes, who are being violated in their rights, this principle is guaranteed both by national and international standards.

The criteria on which the issuance of protection measures is based is the protection and in turn the prevention of any violation that the person may suffer, that is, these measures are issued with the purpose of taking care of the integrity of the person, as regards the effectiveness of the same ones knew to establish that the same if they are effective, inasmuch as the measures that are issued keep away the aggressor from the victim, which takes care of the integrity of the her. To conclude, the interviewee expresses that in order to improve the system in terms of protection measures for victims of violence against women or members of the nuclear family, the enactment of the norm in this case must be given (Integral Penal Organic Code, Official Registry: No. 180, 2014), which as a rule is effective in the protection of victims of this type of crime.

4.2.2. Judge 2

Within the interview to the judge, regarding the measures most applied to victims of violence against women or members of the family nucleus established that within our circumscription as Canton Ambato, the most applied are the issuance of a help ticket, the prohibition of approaching the victim to the victim or in turn ordering the aggressor to leave in cases in which housing is shared with the victim of violence. In relation to the knowledge of the interviewee about the Pro Homine Constitutional Principle, it indicates that within our constitution it is provided in article 11, paragraph 5, which states that the norm must be applied in a manner that is more favorable to its effective validity, in this case the right of the people, for which as judges it is within their obligations in the administration of justice to take into account this principle of application.

Regarding the criteria that are considered for the issuance of protective measures, he indicates that the specific case must be analyzed and in turn the grounds established by the request holder, which would be the Government Attorney Office, which seeks to stop the aggression or prevent a new aggression.

In turn, regarding the effectiveness of the same, he establishes that after the promulgation of the (Organic Comprehensive Criminal Code, Official Gazette: No. 180, 2014), the effectiveness of increased protection measures, since all types of violence is typified as a crime within this Code, giving more relevance to the victims of this type of crime, in turn since the validity of the (Comprehensive Organic Penal Code, Official Registry: No. 180, 2014) is defined the breach of protection measures, which gives a greater guarantee of protection to those who have in their favor this type of measures, this compared to previous types that ignored the provision of these measures.

Regarding the way in which the system of protection measures can be improved in the judicial environment, the interviewee states that although the changes have been positive, one cannot speak of effectiveness at one hundred percent, for this reason the State should create an independent body which can deal with this problem, as established in regulations of other countries, which have as their objective the follow-up of the issuing of the measure, since the State in turn also seeks to preserve and protect the nuclear family, that can be affected by these measures, whereby it is important not only to issue the measures but also value what effectiveness it has, and at the same time seek the regeneration of the family nucleus by means of a follow-up by experts of different areas belonging to this system in advance, as a complement to what is exposed by the interviewee emphasizes that this type of crime happen in all types of homes, not matter the social or cultural nature.

4.2.3. Judge 3

In this interview the Judge knew how to state that the measures most applied to victims of violence against women or members of the family nucleus are firstly the aid ticket, in turn, the prohibition of the aggressor from approaching the victim is often requested, this in relation to the prohibition of acts of harassment or intimidation towards the victim and the departure of the aggressor from the domicile in which he lives with the victim.

Regarding the knowledge of the principle Pro Homine he establishes that this principle has the objective of seeking the well-being of the person, in relation to the protection measures; this implies that they give protection to any member of the family, not necessarily the woman, that is, the issuance of these protective measures seek to safeguard the integrity of the person in general. Regarding the criteria that are taken to grant protection measures, it states that they, to issue protection measures as judges, must consider the rationale that is sent by the Government Attorney and not only a legal basis but also the circumstances of the specific case; based on this they have the power to issue or not such measures, since the criterion of the interviewee is that these can be misused; because of that their effectiveness that according to the respondent criteria they are, can be harmful in certain cases. And as to how to improve the administration of these, he indicates that there must be greater control at the time of their issuance as they must have a valid rationale, that is to say that the need for these measures is verified, to prevent their misuse.

4.2.4. Judge 4

The most applied protection measures are the aid ticket for the benefit of the victim, in the foreground; the second is the prohibition of approaching the victim and then the prohibition of acts of intimidation either by themselves or through other persons and, this being so, that the threat of the aggressor be very high, the exit from the place where he shares the home with the victim is ordered. About the pro homine principle, it states that it arises from human rights and is linked to the person, which aims to protect the rights of the person prima facie, that is, at first sight before the judge. Regarding this principle in relation to the extension of protection measures, the judge must verify the existence of merits, which are remitted by the Government Attorney Office, hence the analysis made by the judge takes into account this principle, in this case in the benefit of the victims, that is, it is the obligation of the judge to take into account them.

In the opinion of the interviewee, there is effectiveness in the protection measures, but taking into account that their effectiveness is influenced in the performance of other factors such as the immediate response by the police servers, another factor stressed by the interviewee is the progress that has been made in criminalizing non-compliance with these measures since the promulgation of the COIP, which has helped to reduce this type of aggression. Regarding the improvement that may exist in terms of protection measures, he indicates that this covers different institutions, first to the Government Attorney Office, since the lack of knowledge about the subject of violence, can take as an impeachment very superficial issues which would contribute nothing to the process itself, another important aspect is the notification to the aggressor, thereby not violating the right of the other party, in terms of improving the effectiveness of the measures themselves, it is indicated that public policies can be established in terms of training on the subject not only to professionals, but children, adolescents, etc.; to divulge the rights and means by which to enforce them in the case of violence, since many times the victim retracts from the complaint filed.

4.3. General Analysis

According to the information collected, it is clear that when typifying violence against women or members of the family nucleus, the indices of these complaints cover the vast majority of the processes that are expedited within the Government Attorney Office, therefore this directly affects the speed with which that they are processed; in turn the change of legislation had a direct change in the process of these crimes, which meant that the protection measures are not immediately available, therefore the victims of this type of crime are in a state of vulnerability; in relation to this the interviewees state that it is necessary to establish grounds for the judge to consider whether they are necessary or not, since they may affect the party denounced, but the integrity of the victim is disregarded and there is a contradiction to a certain extent, since the judges indicated that this principle is of great importance and is linked to the human rights, that is, that the judge must ensure the integrity of the victim in any circumstance, which has been violated as of this change. It is important to recognize that there is a diversity of measures that can be applied, both before, during and after the process, which seeks to take care of the victim’s integrity without affecting the defendant.

5. CONCLUSIONS

After the change of legislation on violence against women or members of the family, there was a change in the procedure in this area. It is clear that the protection measures have been and are a guarantee of security for the victim, and of course there is a problem at the time of requesting them due to the high number of cases that are processed within the Government Attorney Office. That is, that there is no proper issuance of these measures, nor is there any importance or priority to this issue, arguing that within this institution there are more important crimes to be managed, which puts the integrity of the person who establishes the complaint at risk when not receive an immediate guarantee as it was given with the previous law.

The protection measures applicable to cases of violence against women or members of the family are established within the (Comprehensive Criminal Code, Official Registry: No. 180, 2014) Article 558. These measures have not changed in comparison to those established under Law 103. When talking about crimes of violence against women or members of the family, certain protection measures are specified, which seek to protect the victim’s integrity, which in order of greatest use are: Extension of a support ticket in favor of the victim or family members in the case of violence against women or members of the family, prohibition of the accused person from approaching the victim, witnesses and certain persons, in any place where they are, prohibition of the person being prosecuted from carrying out acts of harassment or intimidation against the victim or members of the family nucleus. by himself or through third parties and order of eviction of the person processed from the house or dwelling, if the cohabitation involves a risk to the physical, mental or sexual safety of the victim or witness, since they are premised on the cessation of existing violence and prevent a more serious crime. It is clear that the measures must be issued according to the specific case, but there should be greater application of protective measures such as ordering the respective treatment to which the person processed or the victim and their children must submit, since it is a measure that is not it is used, but in itself, it would be the most effective in this type of crime, seeking stability for both the victim, the aggressor and their family environment. The Pro Homine Constitutional Principle is an interpretive criterion that informs all human rights law, by virtue of which one must resort to the broadest norm, or to the most extensive interpretation, when it comes to recognizing protected rights. This principle is and should be an important instrument for the judge, since the protection of women’s rights are reflected in international regulations, as well as the guidelines for the process. This principle can also be manifested or applied by the other legal operators. Without a doubt, it is a principle that must be observed in turn by the legislator in order not to create regressive-limiting norms of the protection and validity of human rights. The protection measures are dispositions and orders created to protect the security of the people, in order to make effective the care and protection of the victim of the aggression, with respect to the aggression itself and its aggressor; are mechanisms that seek to provide support and protection to victims of aggression and prevent the continuation of these, in turn the Pro Homine principle teaches the basis for interpreting fundamental rights and in turn has a protective sense, which must be adjudged to the interpretation in favor of the weakest and how a jurisdictional decision should be settled, the most beneficial solution should be given to the rights of the individual.

This principle indicates that the judge must select and apply the rule that is most favorable to the human person, for their freedom and exercise of their rights, that is, that the judge, when faced with a request for protection measures, should verify the existence of merits, which are remitted by the Government Attorney Office, hence the analysis made by the judge takes into account this principle, in this case for the benefit of the victims, that is, that it is the duty of the judge to take into account them, that the integrity and security of the victim of violence is at stake, this immediately and effectively as it is part of the Inter-American Convention to Prevent, Penalize and Eradicate Violence against Women. Based on the fundamental parameters for legislation and prosecution of violence against women established by the United Nations, many of them have been met, but there are also some deficiencies that prevent an optimal procedure for this type of crime.

REFERENCES

1. Ardrey, R. (1966). The Territorial Imperative: A Personal Inquiry into the Animal Origins of Property and Nations. New York: Atheneum.

2. Banchs, M. (1966). Violencia de Género. Revista Venezolana de Análisis de Coyuntura, 2, 15. Recuperado de http://www.ucv.ve/fileadmin/user_upload/faces/iies/ANALISIS_DE_COYUNTURA_VOLUMEN_II_No_2_JULIO_DICIEMBRE_1996.pdf#page=15

3. Boulding, E. (2010). La violencia y sus causas: Las mujeres y la violencia social. Paris: UNESCO.

4. Bunch, C. (1991). Los Derechos de la Mujer como Derechos Humanos: Mujer y Violencia Doméstica. Santiago de Chile: Instituto de la Mujer.

5. Cabanellas, G. (2003). Diccionario Jurídico Elemental. Heliasta S.R.L.

6. Castilla, K. (2009). El principio pro persona en la administración de justicia. Cuestiones constitucionales, 20, 65-83. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-91932009000100002&lng=es&

7. Código Orgánico Integral Penal, Registro Oficial Nº 180. Quito. (10 de Febrero de 2014).

8. Comisión Andina de Juristas (2003). Los derechos humanos y la Globalización: avances y retrocesos. Lima, Perú: CAJ.

9. Constitución de la República del Ecuador, Registro Oficial Nº 242 del 20 de Octubre del 2008. (s.f.).

10. Constitución Política de la República del Ecuador, Registro Oficial Nº 278 18 de marzo de 1998. (s.f.)

11. Convención Interamericana de Belem do Para, B.O. (9 de Abril de 1996).

12. Corsi, J. (2006). Maltratos y abuso en el ámbito doméstico. Quito, Ecuador: Patronato San José.

13. Departamento de Asuntos Económicos y Sociales - División para el Adelanto de la Mujer (2010). Manual de legislación sobre la violencia contra la mujer. Nueva York: Naciones Unidas.

14. Díaz, A. (2009). La efectividad de las medidas de protección frente a la violencia familiar. Recuperado de https://trabajadorjudicial.wordpress.com/la-efectividad-de-las-medidas-de-proteccion-frente-a-la-violencia-familiar/

15. Diccionario RAE - Real Academia Española (2001). Diccionario de la lengua española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

16. Fries, L., & Hurtado, V. (2010). Estudio de la información sobre la violencia contra la mujer en América Latina y el Caribe. Chile, Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas.

17. Galarza, M. (2010). La falta de aplicación de las Medidas de Amparo dictadas por la Comisaría de la Mujer y la Familia dentro de las acciones legales, en el primer semestre del año 2009, provoca el incremento de violencia intrafamiliar en el cantón Ambato. Provincia de Tunguragua.

18. Gutiérrez, F. (2005). Manual de Aplicación de Normas Internacionales de Derechos Humanos en el Ámbito Jurídico Ecuatoriano. Guayaquil, Ecuador: Impresos Anabel.

19. Henderson, H. (2004). Los Tratados Internacionales de Derechos Humanos en el orden interno: la importancia del principio Pro Homine. Revista IIDH. 39(29). Recuperado de http://angelduran.com/docs/Cursos/CCDC2013/mod02/02-023_L3-Henderson.pdf

20. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos (2011). Primera Encuesta Nacional de Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género contra las Mujeres Tungurahua. Recuperado de http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/violencia-de-genero/

21. Laurenzo, P. (2005). La violencia de género en la Ley Integral Valoración político-criminal. Revista Electrónica de Ciencia Penal y Criminología, 07-08, 08:1-08:23. Recuperado de http://criminet.ugr.es/recpc/07/recpc07-08.pdf

22. Lorenz, K. (2002). On Agression. Londres: Routledge.

23. Ojeda, L. (2010). Violencia, delincuencia e inseguridad en el Ecuador. Quito: UNAP.

24. Unidas, C. F. (1945). Estados Unidos: San Francisco.

25. Walker, L. (1979). The Battered Women. Nueva York: Harper and Row Publishers.

AUTHORS

Laura V. Córdova P: Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador Sede Ambato, associate attorney in free professional practice for the Legal Advice Study “ESDALEX”, lawyer in free practice, member of Youth UNASUR Ecuador.

laura.cordova@uasb.edu.ec

Víctor H. Córdova A: Business engineer, doctor by the Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain. Professor - researcher, Technical University of Ambato, postgraduate coordinator, FCADM - UTA. Teacher - tutor in master programs, UTA.

victorhcordova@uta.edu.ec

cordovav2@yahoo.es

Héctor F. Gómez A: Computer engineer, doctor by the National University of Distance Education UNED, Spain. Professor - researcher, Technical University of Ambato, postgraduate director - UTA. Teacher - tutor in UTA master programs.

hf.gomez@uta.edu.ec

hfgomez6@gmail.com