doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2016.41.155-180

RESEARCH

INFLUENCE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION OF FIRMS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL COMPACT 10 PRINCIPLES

INFLUENCIA DE LA INTERNACIONALIZACIÓN DE LA EMPRESA EN LA IMPLEMENTACIÓN DE LOS 10 PRINCIPIOS DEL PACTO MUNDIAL DE NACIONES UNIDAS

Carmen Alba Ruiz-Morales1

1She holds a degree in Law from the Autonomous University of Madrid, LLM in Commercial Law from the University of Bristol (UK) and a Master in Management and Management of Global Marketing and New Markets from Universidad Camilo José Cela (UCJC)

ABSTRACT

The UN Global Compact is one of the biggest international CSR initiatives. The Spanish local network is the local network with the largest number of signatories worldwide. The internationalization process of Spanish firms has largely increased in the last years. Previous studies have examined the relationship between internationalization and CSR. This piece of research intends to analyze the progress made in the implementation of the UN Global Compact 10 Principles according to the UN Global Compact Management Model and the influence of the internationalization of firms on it.

KEY WORDS: Corporate Social Responsibility, United Nations Global Compact, Global Compact Spanish Local Network, Internationalization.

RESUMEN

El Pacto Mundial de Naciones Unidas es una de las mayores iniciativas empresariales internacionales de responsabilidad social corporativa. La red española de la iniciativa, es la red local con mayor número de firmantes a nivel mundial. A su vez, el proceso de internacionalización de la empresa española ha ido en aumento en los últimos años provocando que haya un gran número de compañías españolas operando en mercados internacionales. Estudios previos han planteado la relación entre el fenómeno de la internacionalización y la responsabilidad social corporativa de las empresas. En este trabajo se pretende analizar el avance en la gestión de los 10 Principios del Pacto Mundial, según el Modelo de Gestión desarrollado por el Pacto Mundial, y la influencia con el proceso de internacionalización de las empresas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Responsabilidad Social Corporativa, Pacto Mundial de Naciones Unidas, Red Española del Pacto Mundial, Internacionalización Empresarial

Received: 10/10/2016

Accepted: 02/11/2016

Published: 15/11/2016

Correspondence: Carmen Alba Ruiz-Morales

carmen.alba@universidadeuropea.es

1. INTRODUCTION

This article is structured as follows. Initially an introduction is proposed that contextualizes the subject of study, presenting those concepts that determine research. Next, the objectives that are intended to be reached are presented, and then it continues with the description of the methodology that has been used in this piece of research. Finally, the results are discussed and analyzed in an epigraph of discussion, to conclude with the conclusions that are derived, as well as their economic and business implications.

The United Nations Global Compact (PM) is one of the largest initiatives of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) worldwide. Since its inception in 2000, this initiative has experienced rapid growth, consolidating itself as one of the global projects of Greater recognition at the international level (Waddock 2008, Arévalo et al., 2013). At present, more than 12,000 entities, from 170 countries, have joined the initiative (8,000 companies and 4,000 non-business entities). In the Spanish case, 2,600 organizations are linked to it. This makes the Global Compact Spanish Network (REPM) the largest local network in the world (REPM, 2016).

Several studies have considered the relationship between the phenomenon of internationalization and CSR (Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2014). The number of Spanish companies with a presence in international markets is increasing, with the impact of their commercial actions on their corporate results and the markets where they operate (Navarro and García-Marzá, 2009).

For all of these reasons, it seems advisable to study in depth the progress that the internationalized Spanish companies that have adhered to the initiative in the implementation of the Global Compact 10 Principles could have

1.1. Business internationalization

Internationalization involves the expansion of firms across national borders with the aim of producing and selling products and services (Hitt et al., 1997). The concept of internationalization has been studied in recent years and this has led to an extensive literature on this subject. There are a variety of explanatory proposals on the phenomenon of internationalization from different analytical perspectives (Villarreal, 2005). Some authors emphasize internationalization as a corporate strategy of the company (Guisado, 2002, Pla y León, 2004). Others emphasize internationalization as a strategy for the growth and entrepreneurial development of organizations (Luostarinen, 1979). It is also observed that one of the components that are repeated in several definitions is that the process of internationalization is a dynamic process, understood as a phenomenon of an evolutionary and gradual nature (Johanson and Wiedershein 1975; Johanson and Vahlne 1977; Vahlne, 1990, Vahlne and Nordström, 1993, Jarillo and Martínez 1991, Albaum et al., 1994, O’Grady and Lane, 1996, Alonso, 2005, and Rialp and Rialp, 2005).

A conceptual synthesis of the different meanings of the internationalization process could be the one proposed by Villarreal (2005, p.58):

Internationalization of the company is a corporate growth strategy for international geographical diversification, through a long-term evolutionary and dynamic process that gradually affects the different activities of the value chain and the organizational structure of the company, with a commitment and increasing involvement of its resources and capabilities with the international environment, and based on augmentative knowledge.

More recently, the authors Ortega and Espinosa (2015) define entrepreneurial internationalization as “that cultural process of the business world through which companies develop capacities to do business in different countries that constitute markets other than their natural geographical environment”. To the aforementioned authors, corporate internationalization implies that the company develops activities with countries other than the country of origin of the company. These activities may be of a different nature, as long as there are relationships with other markets. Internationalization covers activities such as export of products and / or services, import of products and / or services, commercial implementation through subsidiaries or branches or productive investment abroad.

1.2. The process of internationalization of the Spanish company

The process of internationalization of Spanish companies has been driven mainly by the incorporation of Spain into the European project in the years 1986 and 1992 (Garcia and Crecente, 2014). Since the beginning of the 1990s, Spanish companies have experienced a progressive internationalization of their activities, first focused on finding customers in international markets and later on in the productive area through direct foreign investment (Buisán and Espinosa, 2007).

Foreign trade and international investment of Spanish companies have been characterized by a process of strong growth, leading in recent decades to an increase in the number of Spanish companies operating in international markets (García and Crecente, 2014).

According to data from the Ministry of Commerce, the Spanish companies that dedicated part of their activity to export in 2014 were 147,731. As mentioned, another form of business internationalization is through direct foreign investment (Hollensen and Arteaga, 2010). In 2013, INE registered 4,760 subsidiaries of Spanish companies abroad. This statistic includes companies engaged in industry, construction, commerce and non-financial services. These activities, with the exclusion of non-financial services, focus the universe of Spanish companies abroad (García and Crecente, 2014).

1.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

To de la Cuesta and Valor (2003), CSR management involves recognizing and integrating social, labor, environmental and human rights concerns into management of the company and its operations. In order to meet these concerns, companies will generate policies, strategies and procedures that will also shape their relationships with their partners.

The European Commission’s Green Paper (2001) defines CSR as “the voluntary integration of social and environmental concerns into business operations and relations with all stakeholders”.

In Spain, the Expert Forum convened by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs developed in 2007 (Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 2007, page 7) in more detail this definition:

The Social Responsibility of the Company is, in addition to strict compliance with current legal obligations, the voluntary integration in its government and its management, in its strategy, policies and procedures, of social, labor, environmental and respect for human rights that emerge from the transparent relationship and dialogue with its stakeholders, thus taking responsibility for the consequences and the impacts that derive from its actions. A company is socially responsible when it responds satisfactorily to the expectations of the different interest groups on its operation.

To the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2010), CSR involves all the actions that companies take into account so that their activities have a positive impact on society and affirm the principles and values ??by which they are governed, both in their own internal methods and processes and in their relationship with other stakeholders.

CSR can therefore be defined as the active and voluntary contribution to social, economic and environmental welfare by companies beyond legal requirements (Kolk and Van Tulder, 2010).

1.4. United Nations Global Compact

In the last 20 years, various CSR initiatives or global frameworks have proliferated to encourage and guide CSR and provide companies with procedures to assess, measure and communicate their social and environmental performance (Gilbert and Rasche 2008).

PM is one of the most globally recognized CSR initiatives at the international level (Waddock 2008, Arévalo et al., 2013). It currently has more than 12,000 signatory entities in 170 countries, out of which 8,610 are companies (United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), 2016).

The origin of PM was conceived on 31 January 1999 at the World Economic Forum in Davos in the voice of Kofi Annan, Secretary General of the UN. The initiative materialized on 26 July 2000 when Kofi Annan called on the heads of companies to join a major Pact to implement the commitment made in Davos a year earlier (REPM, 2016).

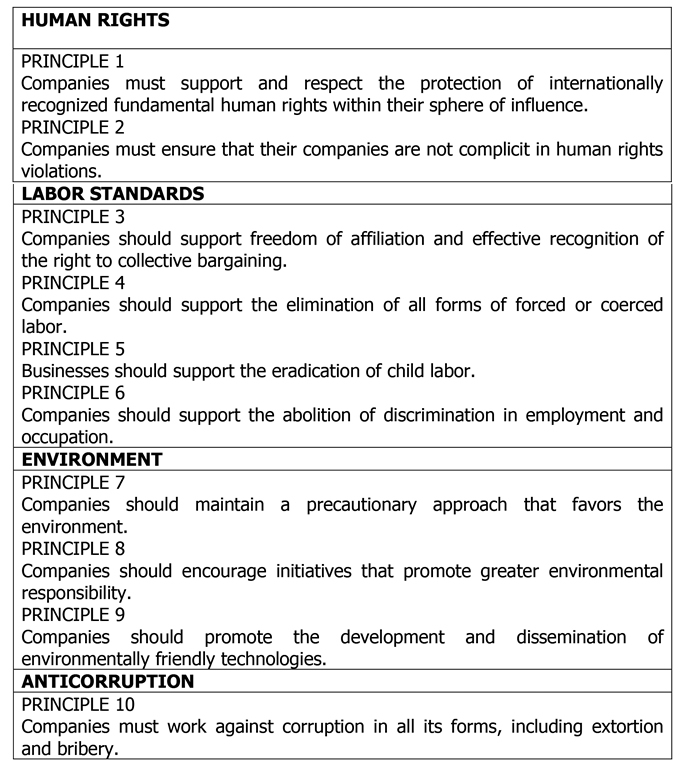

PM is an international initiative of the United Nations that promotes the implementation of 10 universally accepted Principles (see Table 1) to promote CSR in the areas of human rights, labor standards (NNLL), environment (MA) and fight against corruption (CA) in business activities and business strategy (REPM, 2016).

Table 1. The Global Compact 10 Principles

Source: REPM (2016)

The 10 Principles were selected for their relevance to the development of international standards, their importance in advancing social and environmental issues, and the degree to which they had intergovernmental support (Kell and Levin, 2002). Specifically, the Global Compact 10 Principles on Human Rights, NNLL, MA and AC enjoy universal consensus and derive (Kell and Levin, 2002) from the principles established in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ILO Declaration on The Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and the United Nations Convention against Corruption.

Unlike other CSR initiatives, PM has neither the intention nor the capacity to force or measure the behavior of the signatory entities (Ayuso et al., 2016). This voluntariness sometimes raises controversy and, therefore, the initiative has received some criticism (Dasí et al., 2015).

The voluntary approach and the PM relationship with certain multinational companies have been the main focus of criticism of the initiative (Whitehouse, 2003). In some cases, the critical comments originate from different NGOs that have warned about the abuse of certain companies, taking advantage of the UN’s reputation, to improve their image without improving their CSR efforts (Arévalo et al., 2013). Some NGOs have also criticized the lack of transparency regarding compliance with the 10 Principles (Hughes et al., 2001, Ruggie 2001, Hemphill 2005).

PM, as Arévalo et al. (2013) point out, has made progress in this regard by introducing a more complete communication platform for its signatories with the aim of supporting them during the different levels of implementation of the 10 Principles.

In Spain, the initiative of PM begins its activity with Rafael del Pino Foundation in the year 2002, and it is the 15 of November of 2004 when the Spanish Association of the Global Compact is created, now known as the Global Compact Spanish Network (REPM).

REPM currently has 2,600 entities, out of which 12% are large companies, 72% are SMEs and 16% are other entities (third sector, trade unions / business associations and educational institutions) (REPM, 2016). Since its inception, the Spanish Network has been one of the first national platforms of PM and the Local Network with the largest number of signatories.

1.5. Global Compact Management Model

With the aim of providing companies with a model that facilitates the companies’ efforts in integrating the 10 Principles, PM designed in 2010, together with Deloitte, the PM Management Model (UNGC, 2010) . It is a tool that ensures that the sustainability strategy of companies is aligned with the PM 10 Principles.

Figure 1. Global Compact Management Model.

Source: UNGC (2010)

As can be seen in Figure 1, the model contains 6 steps: commit, evaluate, define, implement, measure and communicate. The model explains what each step implies for organizations:

1. Commit: this step implies for the signatory entities the commitment of their leaders to integrate the principles of PM into their strategies and operations and to take actions in support of the broader objectives of the UN in a more transparent way (UNGC 2010).

2. Evaluate: the next step of the model is related to the evaluation of risks, opportunities and impacts in all areas of PM. Once the company is committed to PM and in support of the objectives of the UN, in this step, the company evaluates its risks and opportunities, as well as the impact of its operations and activities on the thematic areas, on an ongoing basis, in order to develop and refine its objectives, strategies and policies.

3. Define: in the third step of the model, the company defines objectives, strategies and policies. In line with the risk assessment set out in the previous step, the company develops and defines specific objectives and indicators to its operational context. In addition, the company creates a work plan to carry out the designed program.

4. Implement: In the next step, the model proposes to implement strategies and policies in the company and along the value chain. In this step, the model establishes that the company develops and guarantees continuous adjustments to its daily and essential processes of the company, involves and educates its employees, develops capacity and resources and works with its value chain partners to approach and implement Its CSR strategy.

5. Measure: step number five consists of measuring and tracking the impacts and checking progress towards the set goals. The tool proposes that in this step the organization should adjust its performance management systems to collect, analyze and monitor the performance indicators established in the “Evaluate” and “Define” steps. Progress is contrasted with the set goals and, if necessary, adjustments are made to improve performance.

6. Communicate: The last step is to communicate progress and strategies and involve stakeholders for continuous improvement. During this step, the company communicates its progress and strategies aimed at implementing its commitment and engages stakeholders to identify ways to continuously improve performance.

The scope of the model focuses on the steps that companies take once they have made their commitment to PM. It is a dynamic and continuous process, designed to help companies achieve higher levels of performance over time (UNGC, 2010).

1.6. Relationship among CSR, Global Compact and entrepreneurial internationalization

Several studies have considered the relationship between the phenomenon of internationalization and CSR (Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2014).

Several authors (Bansal, 2005; Perrini et al., 2011) point out the pressures received by different interest groups for international companies to carry out socially responsible behavior.

To Aguilera-Caracuel et al. (2014), internationalized companies can choose to homogenize social initiatives in the different countries in which the company operates, and as a result, companies could strengthen their transparency (Christmann, 2004) reputation and legitimacy. (Bansal, 2005). Aguilera-Caracuel et al (2014) emphasize that reputation and legitimacy are especially important in companies with an international presence and are directly linked to the implementation of advanced CSR practices (Fombrun, 1996).

Ayuso et al (2016) suggest that internationalized companies have a greater opportunity to learn because they are exposed to new and different ideas from diverse national contexts and various social, cultural and environmental challenges. Thus, some authors emphasize international experience as a resource-based variable (Bansal, 2005) and others consider it to be a knowledge-based variable (Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2012). Companies with international experience can take advantage of the knowledge gained in different jurisdictions and develop a set of best CSR practices based on acquired learning (Ayuso et al., 2016).

To Ayuso et al. (2016) companies operating in international markets also gain experience in communicating, negotiating and establishing relationships with stakeholders, and will thus be able to develop greater sensitivity in how to adapt their CSR policies to the local context.

Several authors have suggested that institutional pressures have pushed multinationals to higher standards of CSR (Sharfman et al., 2004). In addition, Ayuso et al (2016) point out the incentives they raise in this regard to increase CSR policies, the pressure exerted on organizations by the different interest groups of the country of origin of the company, as well as the role of scrutiny and monitoring carried out NGOs on the activities of companies.

Aguilera-Caracuel et al. (2014), in turn, emphasize that the influence of the internationalization of companies in their CSR has been widely debated, having a diversity of points of view.

On the one hand, there are authors who talk about the complexity and difficulty of implementing CSR policies in the different markets where the company operates. Thus, Peng et al (2008) emphasize that internationalization can lead to high coordination costs by handling a large amount of information from a wide range of environments. Van Raaij (1997), in turn, highlights the difficulty of standardizing CSR practices due to the fact that companies have to interact with different cultures; levels of differentiated economic development, as well as meeting diverse needs of interest groups. On the other hand, Surroca et al (2013) point out that certain companies could carry out opportunistic social behavior by locating certain activities in countries with looser social and environmental legislation.

On the contrary, there is research that emphasizes that, through internationalization, companies will be exposed to greater social (Strike et al, 2006) and environmental (Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2013) learning. Thus, Aguilera-Caracuel et al (2014) emphasize that internationalization can enable companies to acquire valuable knowledge from different markets that results in substantial improvement in their social performance (Strike et al., 2006). To Keinert (2008), CSR can positively contribute to internationalization processes.

There is, therefore, a certain consensus that there is lack of exploratory studies and conclusive answers on certain relevant aspects that shed light to the relationship between CSR and internationalization (González-Pérez and Leonard, 2015).

The relationship among PM, internationalization and CSR has been analyzed by authors such as Ruggie (2001), Thérien and Pouliot (2006) and Cetindamar and Husoy (2007). In reviewing the literature on this subject, it has been observed that there are different points of view.

Some authors point out that there is a clearly beneficial relationship and others have an opposite point of view. In addition, recent studies have observed that the fact that companies are internationalized does not necessarily mean that this is a factor that favors the implementation of the 10 Principles (Ayuso et al., 2016). Among other aspects, the authors did research on whether internationalized companies were more motivated to allocate tangible and intangible resources to the implementation of the PM 10 Principles. Contrary to what was expected, the authors found that internationalized companies feel less inclined to use their resources to implement the PM principles by observing that the internationalization of the company does not have a positive effect on implementation of the PM principles.

Rasche (2009) and Ayuso and Roca (2010) emphasize that, while certain pieces of research explore the factors that seem to influence the decision to adhere to the initiative, there are still few empirical studies on the impact of this initiative on the current practices of the companies adhered to and the implementation of the 10 Principles in companies. The fact that there is little literature on this subject could be due to the fact that this is a relatively recent initiative (Cetindamar and Husoy, 2007) and difficult access to data. The first empirical studies on the initiative were carried out by McKinsey & Company (2004) and United Nations Global Compact (UNGCO, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012).

2. OBJECTIVES

Out of the reviewed literature, it can be concluded that the relationship between PM and the process of internationalization of companies raises a great scientific interest, but to date its study has not been sufficiently deepened. Based on the previous conclusion, the present article raises as main objective to know and analyze the progress in management of the PM 10 Principles and the influence of the internationalization of the Spanish companies that signed the initiative during the 2004-2014 period, through the following question:

Is the process of internationalization of companies a determining factor for the degree of progress and commitment in management and implementation of the PM 10 Principles?

From the previous question, the formulation of the hypothesis of this piece of research derives:

The process of internationalization of companies is not a determining factor for the progress and commitment in management and implementation of the Global Compact 10 Principles.

3. METHODOLOGY

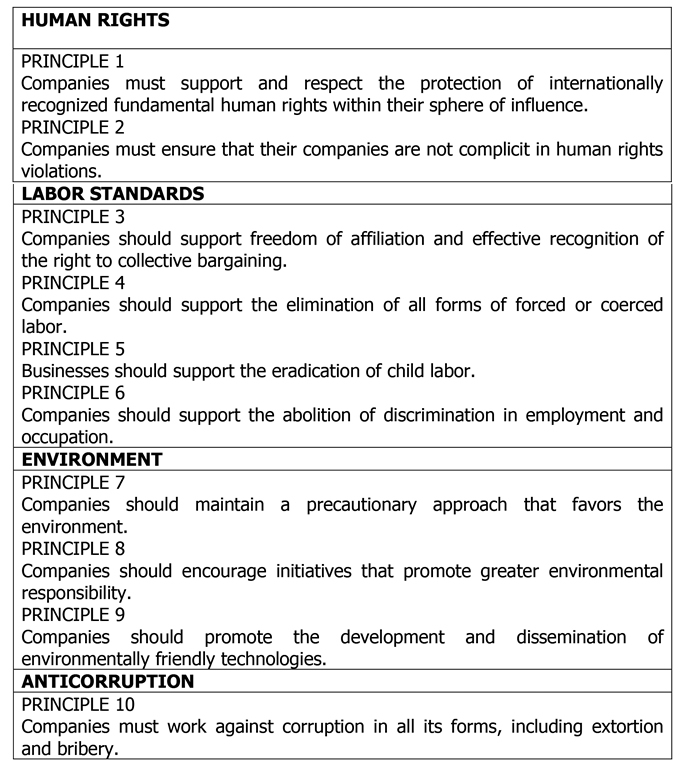

For the accomplishment of this paper, a descriptive exploratory study has been carried out. It has studied the effects that the process of internationalization of Spanish companies can cause in the progress in implementation of the PM 10 Principles. The period of study is from 2004 to 2014. The collection of data was done through sending a questionnaire by REPM on the occasion of its tenth anniversary. Data collection took place during the months of June and July of 2014 (Table 2)

Table 2. Sample data sheet

Source: Made by the author

Out of the 215 companies that answered the questionnaire, 47% were internationalized. Among the internationalized companies that answered the survey, 45% were SMEs and 55% were large companies.

In addition, the author has held numerous meetings with the team and the directorate of REPM, both for the preparation of research and after research, to analyze and discuss the results obtained.

4. DISCUSSION

In this section, we will present the sample information that will try to answer the question of research. We have differentiated large companies from SMEs and, in turn, whether they were internationalized or not.

To measure the degree of progress and commitment to the PM initiative, companies were asked in the questionnaire what steps of the PM Management Model they had completed and to what degree. This tool allows us to indirectly measure the degree of progress without considering only the particular criterion of the companies in their degree of progress. It is, therefore, a procedure subject to a lesser extent to the subjectivity of each company and which provides results with greater comparability.

For each of the four areas in which the initiative (DHHH, NNLL, MA and AC) worked, the evolution of the steps proposed by the PM Management Model was questioned:

1. evolution in the definition of risks

2. evolution in the definition of policies

3. evolution in the definition of objectives

4. evolution of implementation of actions

5. evolution of the measurement of results

6. evolution in the communication of results

In each of the steps and for each area of PM, there are three possible values: value 1 when the degree of achievement is zero, 2 when the degree is average and 3 when the degree of attainment is maximum. In order to synthesize this vast information in a simple way, differentiating large companies from SMEs and internationalized and non-internationalized companies, we have chosen to construct a synthetic indicator or simple compound for each area of ??analysis described below.

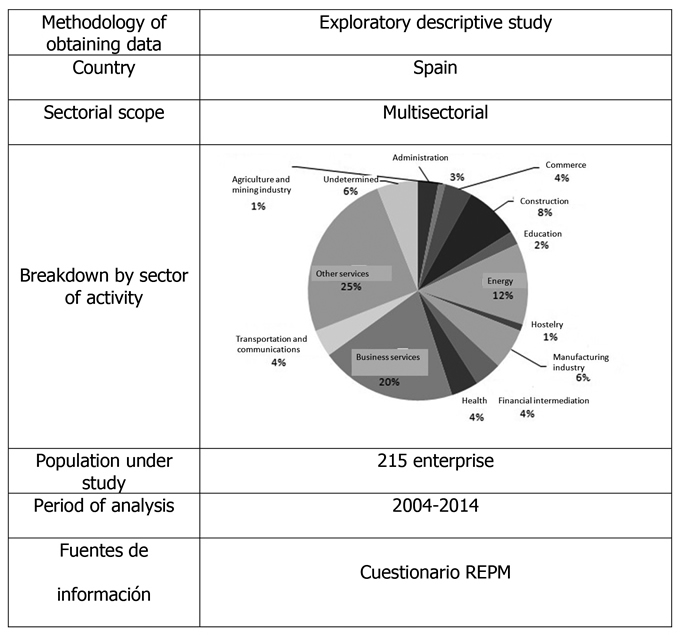

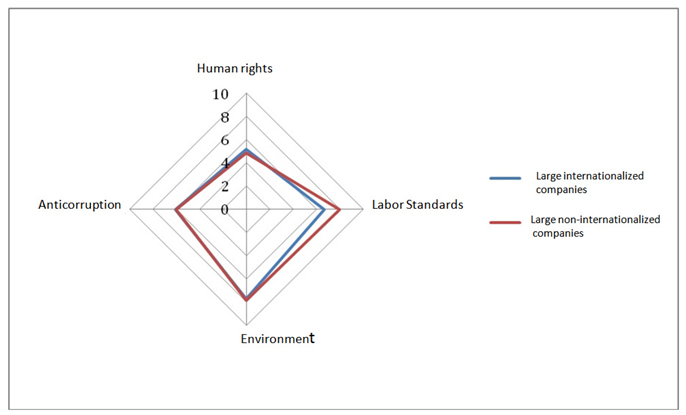

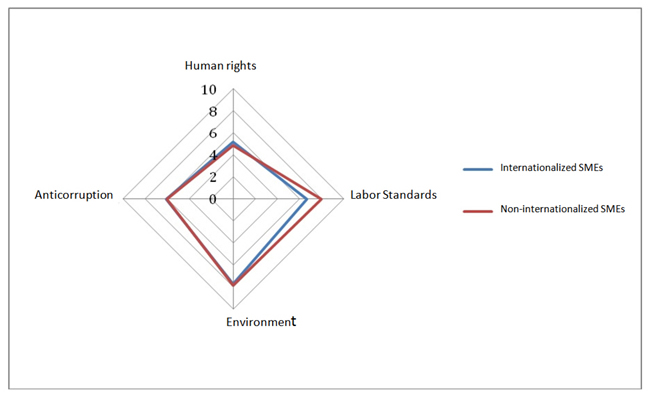

We begin by performing a transformation of the sum of scores obtained in each step in order to obtain a scale from 0 to 10. The minimum score in each area of ??6 points (null achievement level in each of the six steps) is transformed in value 0 and the maximum score in each area of ??18 points (complete achievement level in each of the variables) in 10 points. Figure 2 and Figure 3 have created rectangles whose vertices are the average score obtained in each area for each subsample of analysis.

Figure 2. Advancement by areas according to PM Management Model large companies.

Source: made by the author based on data from the questionnaire sent by REPM

Figure 3. Advancement by areas according to PM SMEs Management Model

Source: made by the author based on data from the questionnaire sent by REPM

The first conclusion is that there are no large, generalized or significant differences between internationalized and non-internationalized companies, regardless of size. However, in the case of large companies, it is observed that the internationalized ones are below the level of evolution in the area of ??NNLL. In the case of SMEs, a similar phenomenon occurs in the area of ??Human Rights.

Generally speaking, larger companies score higher in all areas, especially NNLL and AC.

There is a remarkable fact, the evolution in the area of ??MA of all companies, especially the big ones, resulting in some levels of achievement of relevant factors. This may partially be due to the overrepresentation of the energy sector in the sample.

Among the large companies, the area with a lower degree of progress according to the PM Management Model is that of HR, followed by the CA area. In both the NNLL and MA areas the degree of progress is remarkable.

As for SMEs, the areas with the greatest progress in their management are those of MA and NNLL, the areas of HR and AC being the ones with less progress.

After data analysis, it can be affirmed that there is quantitative evidence to prove the validity of the hypothesis. It is shown that internationalized companies do not necessarily advance management and implementation of the 10 Principles more than non-internationalized companies. Therefore, it could be said that the process of internationalization of companies is not a determining factor for the progress in management and implementation of the Global Compact 10 Principles.

5. CONCLUSIONS

If we analyze the degree of implementation according to the PM Management Model, it can be concluded that there are no generalized or significant differences between internationalized and non-internationalized companies, regardless of their size.

REPM, they point out that they are aware that companies have better understanding of how to act in the NNLL area. For this reason, since 2013 they have developed specific HR programs for SMEs and large companies and programs in the area of ??CA, specifically for SMEs, with the aim of guiding and equipping companies in these areas.

Larger companies score higher in all areas, especially in NNLL and AC. In fact, since 2013 PM has developed specific programs for SMEs in the areas of HR and AC to improve their performance in these areas.

There is remarkable evolution in the area of MA of all companies, especially the big ones, resulting in some levels of achievement of relevant factors. This may be partially due to the over-representation of the energy sector in the sample. Also, this could be due to the fact that there are more standards and certificates for the area of MA (ie: ISO 14000).

In line with what Ayuso et al (2016), it is observed that the internationalized companies are less inclined to deploy their resources to implement the PM 10 Principles. This result may suggest that operating in international markets forces companies to devote a large amount of their available tangible and intangible resources to other objectives (Peng, 2001) to the detriment of improving their application of the PM 10 Principles (Ayuso et al. Al., 2016).

On the other hand, this result may indicate that companies exposed to an international context (and the challenges addressed by the 10 Principles) find in the international markets such complexity that makes it difficult to implement CSR policies in these markets. This conclusion would be in line with what was pointed out by Peng et al (2008) and Van Raaij (1997), who emphasize that internationalization can lead to high costs of coordination by handling a large amount of information that comes from very diverse environments and, in turn, makes it difficult to standardize CSR practices due to the fact that companies have to interact with different cultures and levels of economic development.

This means, according to PM representatives, that it is still a pending task to improve the development of CSR policies in the markets to which companies come when they are internationalized.

It would be advisable, therefore, that internationalized companies should develop a set of measures relating to their CSR policies in the new countries where the company operates. CSR should be integrated in all the processes of the company in its international expansion, otherwise, the data seem to indicate that there are no mechanisms to guarantee CSR policies when companies expand internationally.

The complication of applying CSR policies in certain international markets may be more complex than in the domestic market. From the various conversations with the directorate of REPM, it follows that, in the case of the NNLL area, which is the area where performance was lower by applying the Global Compact Management Model, the fundamental reason could be that in many of the markets where companies are internationalized, legislations are more lax and there is less control. In addition, according to the directorate of REPM, other reasons could be related to lack of maturity in certain markets to apply CSR policies, the cost of controls to verify if policies are being implemented, management complexity entailed in verification and, sometimes, it could be due to lack of training of the people responsible for applying these policies in the subsidiaries. However, in many of these markets, it is necessary to develop business sustainability policies that improve corporate policies and practices.

On the other hand, the involvement of companies in CSR projects seems to have taken a path of no return. The preponderance of Spanish companies in REPM is another example of this. Also, the internationalization of the company as a form of innovation (Andersen, 1993), in the face of an unfavorable international economic situation and a depressed internal market (especially since 2008) is part of the strategy of Spanish companies that need to diversify their sales (Ortega, 2010).

However, this exploratory study intends to lay the foundations for new research that will bring new conclusions to the study of CSR and the relationship and implications of this with the process of business internationalization that, on the other hand, will contribute to solving and contrasting questions and issues that other authors have been raising in recent years about this.

5.1. Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted within its possible limitations.

Considering the previously mentioned results and conclusions, it is important to emphasize that this study is confined to the signatories of PM of the Spanish business environment. Although the extrapolation of the conclusions to other markets could be considered, further empirical deepening and testing is desirable. Another limitation of this piece of research is the modest response rate to the survey. Non-response is a generalized phenomenon in the sample statistics due mainly to the fact that companies are fed up with a growing number of questionnaires from different sources. The statistical burden is especially relevant for smaller companies in which there are no specialized resources to collect and transfer the required information with quality minimums in the established deadlines. Obtaining a response rate of 11-20% in the field of Social Sciences seems to be frequent (Cetindamar and Arikan, 2004; McKinsey, 2004). Therefore, the response obtained is within the expected range in this area of ??knowledge.

In addition, the possible greater involvement or better assessment, both of PM and of REPM, of companies that have satisfactorily answered the questionnaire should be kept in mind, since it seems reasonable to think that companies that have answered the questionnaire on time are those that are more involved in everything that implies adhering to the initiative.

5.2. Future lines of research

In the review of the literature it is detected that the subject of this piece of research is in an emerging state so it would be convenient to continue to delve into this field.

Our research has been carried out in the Spanish business environment. In this sense, it would be of great interest to analyze the conclusions described here in order to verify if they are applicable to other countries and economic environments. For this reason, we propose to replicate the study in other countries and to analyze if the results obtained are generalizable to any geographical environment.

This study has been carried out for the 2004-2014 period, so there are companies that have adhered relatively recently compared to others that are signatories since the origin or soon after. For this reason, there are companies that have had a shorter implementation time of the 10 Principles than previously adhered companies. It would be interesting to propose a similar study to carry out a comparative study later.

Also, future studies could focus on analyzing what differences exist in the implementation of the 10 Principles among companies that carry out different activities at an international level. Thus, it would be of great interest to analyze if there are differences between those companies that have factories abroad versus those that have commercial subsidiaries. Likewise, it would be of great research interest to analyze the possible differences among companies operating in different countries and to observe if there are substantial differences in the way companies act according to the different countries where they operate.

The influence of the reasons driving the company to internationalize would also be interesting to be researched in the future. A priori, one could think that there could be differences, for example, in the behavior of companies that are internationalized in search of new clients and those seeking relocation to lower costs. Finally, it would be of interest, both to the academic world and to those who are dedicated to business management, to analyze the behavior and perception of the analyzed entities taking into account the sector of activity of each company with the objective of observing if there are substantial differences by sectors.

REFERENCES

1. Aguilera-Caracuel J, Hurtado-Torres NE, Aragón-Correa JA (2012). Does international experience help firms to be green? A knowledge-based view of how international experience and organizational learning influence proactive environmental strategies. International Business Review, 21(5):847-861.

2. Aguilera-Caracuel J, Hurtado-Torres N, Aragón-Correa JA,. Rugman A (2013). Differentiate deffects of formal and informal institutional distance between countries on the environmental performance of multinational enterprises. Journal of Business Research, 66(12):2657-2665.

3. Aguilera-Caracuel J, Delgado-Márquez, BL, Vidal-Salazar MD (2014). The influence of internationalization on firm corporate social performance. Cuadernos de Gestión, 14(02):15-32.

4. Albaum G, Strandskov J, Duerr E, Dowd L (1994): International Marketing and Export Management. Cambridge: Addison-Wesley.

5. Alonso JA (2005). El proceso de internacionalización de la empresa: Algunas sugerencias para la política de promoción. Claves de la Economía Mundial. ICEX, pp. 71-80.

6. Andersen O (1993). On the internationalization process of firms: A critical analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(2):209-231.

7. Arévalo JA, Aravind D, Ayuso S, Roca M (2013). The Global Compact: Analysis of the motivations of adoption in the Spanish context. Business Ethics: A European Review, 22(1):1-15.

8. Ayuso S, Roca M (2010). Las empresas españolas y el Pacto Mundial. Cátedra De Responsabilidad Social Corporativa, 8.

9. Ayuso S, Roca M, Arévalo JA, Aravind D (2016). What Determines Principle-Based Standards Implementation? Reporting on Global Compact Adoption in Spanish Firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(3):553-565.

10. Bansal P (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate us tainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3):197-218.

11. Cetindamar D, Arikan Y (2004). Diffusion of Environmentally Sound Technology: Findings from the Turkish Case. 12th International Conference of Greening of Industry Network, 6-11th of November, Hong Kong.

12. Cetindamar D, Husoy K (2007). Corporate social responsibility practices and environmentally responsible behavior: The case of the United Nations Global Compact. Journal of Business Ethics, 76(2):163-176.

13. Christmann P (2004). Multinational companies and the natural environment: Determinants of global environmental policy standardization. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5):747-760.

14. Comisión Europea (2001). Libro Verde: Fomentar un marco europeo para la responsabilidad social de las empresas. CEE.

15. Dasí M, Dolz C, Linares-Navarro E (2015). Why Do Spanish Firms Engage in the Global Compact Initiative? An Explanation from Institutional and Social Identity Theories. The UN Global Compact: Fair Competition and Environmental and Labour Justice in International Markets (pp. 123-144). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

16. De-la-Cuesta M, Valor C (2003). Responsabilidad social de la empresa. Concepto, medición y desarrollo en España. Boletín Económico de ICE, Información Comercial Española, 2755, 7-20.

17. El Sector Exterior en 2014 (2015). Boletín Económico De ICE, Información Comercial Española, (3065), Secretaría de Estado de Comercio.

18. García A, Crecente FJ (2014). La internacionalización de la empresa española: Oportunidades y riesgos. Madrid: Fundación MAPFRE.

19. Gilbert DU, Rasche A (2008). Opportunities and problems of standardized ethics initiatives: A stakeholder theory perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3):755-773.

20. González-Pérez MA, Leonard L (2015). The Global Compact: Corporate Sustainability in the Post 2015 World. In: Beyond the UN Global Compact: Institutions and Regulations (pp. 1-19). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

21. Guisado M (2002). Internacionalización de la empresa: estrategias de entrada en los mercados extranjeros. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide.

22. Hemphill TA (2005). The United Nations Global Compact: the business implementation and accountability challenge. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 1(4):303-316.

23. Hitt MA, Hoskisson RE, Kim H (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40(4):767-799.

24. Hollensen S, Arteaga J (2010). Estrategias de marketing internacional. Pearson- Prentice Hall.

25. Hughes S, Wilkinson R, Humphreys D, Macmillan T, Rae ID (2001). The Global Compact: promoting corporate responsibility?Environmental Politics, 10(1):155-177.

26. Jarillo JC, Martínez J (1991). Estrategia Internacional. Más allá de la exportación. Madrid: Mc Graw-Hill.

27. Johanson J, Vahlne J (1977). The internationalization process of the firm. a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8, 23-32.

28. Johanson J, Vahlne JE (1990). The mechanism of internationalisation. International marketing review, 7(4):11-24.

29. Johanson J, Wiedersheim F (1975). The internationalization of the firm—fourswedish cases 1. Journal of Management Studies, 12(3):305-323.

30. Keinert C (2008). Corporate social responsibility as an international strategy. Springer Science & Business Media.

31. Kell G, Levin D (2002). The evolution of the Global Compact network: An historicexperiment in learning and action. The Academy of Management Annual Conference, Denver, Agosto, 11-14.

32. Kolk A, Van-Tulder R (2010). International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. International businesss review, 19(2):119-125.

33. Luostarinen R (1979). The internationalization of the firm. Helsinki: Helsinki School of Economics.

34. McKinsey & Company (2004). Assessing the Global Compact´s Impact. United Nations Global Compact. Recuperado de http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/news_events/9.1_news_archives/2004_06_09/imp_ass.pdf.

35. Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales (2007). Informe del Foro de Expertos en Responsabilidad Social de las Empresas. Recuperado de http://www.empleo.gob.es/es/sec_trabajo/autonomos/economia-soc/resposocempresas/foro_expertos/contenidos/INFORME_FOROEXPERTOS_RSE.pdf.

36. Navarro F, García-Marzá D (2009). La RSC en el marco de la cooperación al desarrollo y la internacionalización de la empresa española en países de renta media y rehabilitación post bélica. Revista española del tercer sector, 11, 115-143.

37. O’Grady S, Lane HW (1996). The psychic is tanceparadox. Journal of international business studies, 27(2):309-333.

38. Organización Internacional del Trabajo (2006). Declaración tripartita de principios sobre las empresas multinacionales y la política social. Recuperado de http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_124924.pdf.

39. Ortega A (2010). La internacionalización de la empresa española y la decisión de exportar como solución a la crisis. Revista de Sociales y Jurídicas, 6, 88-111.

40. Ortega A, Espinosa J (2015). Plan de internacionalización empresarial. Manual práctico. Madrid: ESIC Editorial.

41. Peng MW, Wang DYL, Jiang Y (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5):920-936.

42. Perrini F, Russo A, Tencati A, Vurro C (2011). Deconstructing the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1):59-76.

43. Plá J, León F (2004). Dirección de empresas internacionales. Madrid: Pearson Educación.

44. Rasche A (2009). A necessary supplement’: What the United Nations Global Compact is and is not. Business and Society, 48(4):511-537.

45. Red Española del Pacto Mundial (2016). Recuperado de http://www.pactomundial.org/.

46. Rialp A, Rialp J (2005). Las formas actuales de penetración y desarrollo de los mercados internacionales: Caracterización, marcos conceptuales y evidencia empírica en el caso español. Claves de la Economía Mundial, ICEX, pp. 99-108.

47. Ruggie JG (2001). Global_governance.net: The Global Compact as learning network. Global Governance, 7(4):371-378.

48. Sharfman M, Shaft T, Tihanyi L (2004). A model of the global and institutional antecedents of high-level corporate environmental performance. Business and Society, 43(1):6-36.

49. Strike VM, Gao J, Bansal P (2006). Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6):850-862.

50. Surroca J, Tribó JA, Zahra SA (2013). Stakeholder pressure on MNEs and the transfer of socially irresponsible practices to subsidiaries. Academy of Management Journal, 56(2):549-572.

51. Thérien JP, Pouliot V (2006). The Global Compact: shifting the politics of international development? Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 12(1):55-75.

52. United Nations Global Compact & Deloitte (2010). UN Global Compact Management Model. Recuperado de https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/news_events/9.1_news_archives/2010_06_17/UN_Global_Compact_Management_Model.pdf.

53. United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) (2016). Recuperado de https://www.unglobalcompact.org/.

54. United Nations Global Compact Office (2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2014). Annual review. United Nations Global Compact Office.

55. Vahlne JE, Nordström KA (1993). The internationalization process: impact of competition and experience. The International Trade Journal, 7(5):529-548.

56. Van-Raaij F (1997). Globalization of marketing communication? Journal of Economic Psychology, 18 (6):259-270.

57. Villarreal O (2005). La internacionalización de la empresa y la empresa multinacional: una revisión conceptual contemporánea. Cuadernos de Gestión, 5(2):55-73.

58. Waddock S (2008). Building a new institutionalinfrastructureforcorporateresponsibility. TheAcademy of Management Perspectives, 22(3):87-108.

59. Whitehouse L (2003). Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Citizenship and the Global Compact. Global Social Policy, 3 (3):299-318.

AUTHOR

Carmen Alba Ruiz-Morales

Law degree from the Autonomous University of Madrid, LLM in Commercial Law from the University of Bristol (UK) and Master in Management and Direction of Global Marketing and New Markets from Camilo José Cela University (UCJC). She has developed all her professional activity in the world of foreign trade and the internationalization of the company: first in the Public Administration (Commercial Office of the Spanish Embassy in New York, USA) and later in SMEs and multinationals. Currently, she combines teaching in various universities and Business School with her activity of specialized consulting in strategy and business internationalization. In addition, she is a doctoral student in the Communication program of the UCJC and her area of research is the adhesion to the United Nations Global Compact of business sustainability and the process of internationalization of Spanish companies.