doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2016.40.104-121

RESEARCH

PSYCHOLOGICAL VARIABLES WHICH BOOST DISSEMINATION OF RUMOR

VARIABLES PSICOLÓGICAS QUE IMPULSAN LA DIFUSIÓN DEL RUMOR

María Elena Mazo Salmerón1

1San Pablo CEU University. Spain.mariaelena.mazosalmeron@ceu.es

ABSTRACT

The spreading of rumors is a process based on complex mechanisms, such as the psychological processes that will be identified and analyzed in this article. The rumor, as an example of interpersonal and spontaneous message, holds a special relevance nowadays for its influence in the media, especially in the digital media. Since the Internet arose, rumors have exponentially multiplied their diffusion coverage. Several main effects have been generated: from disinformation to spreading of true “viruses” in the current society. In companies and other organizations, there are conflicts that generate a favorable environment for this kind of messages. The study of persuasion, the cognitive processes, the psychological atmosphere which stimulates rumor spreading and testimony, collaborate to better understanding of the phenomenon under study, as a peculiar and rebellious case among the different kinds of messages generated in the media and corporate environments –companies and institutions.

PALABRAS CLAVE: rumor, variables psicológicas, difusión- persuasión, prejuicios, procesos cognitivos

RESUMEN

La difusión del rumor es un proceso que toma cuerpo mediante mecanismos muy complejos, entre los que se encuentran los procesos psicológicos que se van a identificar y analizar en este artículo. El rumor, como ejemplo de mensaje interpersonal y espontáneo, cobra una especial relevancia en la actualidad por su influencia en los medios de comunicación. Entre ellos cabe destacar su incidencia en los medios digitales. Desde que apareció Internet se ha multiplicado exponencialmente su cobertura de difusión. Además, se han producido destacados efectos, desde la desinformación, hasta la propagación de verdaderos “virus” en la sociedad actual. En las empresas y demás organizaciones también aparecen conflictos que generan un verdadero caldo de cultivo para este tipo de mensajes. El estudio de la persuasión, los procesos cognitivos, el entorno psicológico que favorece la propagación de rumores y el testimonio, entre otros, va a colaborar en la mejor comprensión del fenómeno objeto de estudio, como un caso peculiar y rebelde entre los diferentes tipos de mensajes que se generan en los medios y en los entornos corporativos –empresas e instituciones-.

PALABRAS CLAVE: rumor, variables psicológicas, difusión- persuasión, testimonio, prejuicios , procesos cognitivos

Recibido: 21/03/2016

Aceptado: 03/06/2016

Publicado: 15/07/2016

1. INTRODUCTION

From a polyhedral reality to the prism of Psychology

In the article published by the author in the journal Opción (Mazo Salmeron, M.E .: 2015), it is stated that the rumor is a multidimensional communication process that must be analyzed from a multidisciplinary perspective. This consideration is shared by most communication researchers. A. Ortí and F. Conde are a clear example (J.M. Delgado and Gutierrez, J., 1994). In fact, Conde proposes an interesting process of reduction and formalization of this “polyhedral” reality (Delgado, JM & Gutierrez, J., 1994, p 97-119), starting with the classification into levels suggested by Ortí –level of facts, level of discourse and level of motivational processes- it suggests clearing this phenomenon from the different disciplines of study.

This paper analyzes the psychological variables that drive the actors in this type of communication to disseminate and propagate, spontaneously and exponentially, a type of so peculiar messages.

Dissemination of rumors occurs through a very complex process influenced by different variables. These include psychological factors impinging upon this type of interpersonal and spontaneous message. The scope of the study will be, on the one hand, the derivative of its impact on the media. Especially, we must include digital media -from the moment the Internet arose, rumor dissemination has exponentially been multiplied and prominent effects, from misinformation to the spread of “viruses”, are taking place. On the other hand, the author is interested in analyzing the corporate environment of companies and other organizations.

From the point of view of psychology, there are many factors that influence rumor: persuasion, cognitive processes, the psychological environment favoring the dissemination of rumors and testimony, among others, will help to better understand this phenomenon under study. Rumor is a peculiar and “rebellious” case among the different types of messages that are generated in the media and in corporate contexts.

2. OBJECTIVES

The following research objectives are established:

– Analysis of the psychological variables that determine the dissemination of rumor. The study will focus on the more determining psychological factors that favor the dissemination of these messages.

– Arrive at conclusions of interest for better understanding of this so peculiar phenomenon. The fact that its process is spontaneous and ambiguous greatly hinders research. For this reason, the author aims to provide rigor and order in these complex communicative contexts.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Documentary phase: limited bibliography, abundant and lax digital documentation

In this first phase of documentary research, it has been shown that there is a clear disproportion between the literature devoted to the psychological elements of rumor and sources provided by the Internet. Lax writings about rumor proliferate and only a few address its psychological processes in a more detailed and systematic way. In that sense, the author has sought high-quality documentary sources to provide her arguments with rigor. This searching phase has remained until the final closing phase of this writing. The valid prior knowledge about rumor in psychology is characterized by having been approached by few authors.

3.2. Methodology of social sciences: a spontaneous and “elusive” case

Below we analyzed the material obtained by applying critical thinking processes necessary to achieve the necessary conclusions. It should be noted that this object of study is a spontaneous, “slippery” and frequent message in the communicative day after day of individuals. It occurs on a daily basis but scholars rarely stop to delve into its functioning. This phase of analysis is required to provide the considerations proposed in this document with seriousness.

Regarding the methodology used by the author, we should mention the one corresponding to a paper of theoretical research of a social phenomenon. Therefore, we should apply the analysis methodology of social sciences.

Diez Nicolas establishes the following limits as methodological problems of social sciences(Diez Nicolas, J., 1986): first it should be kept in mind that academic findings cannot be considered universal because of the relativity conferred by every culture and era upon the social fact; In addition, the continuing evolution of the behavior of individuals of a given society causes scientific prediction to always be probabilistic; it also include the inability to propose objective causes due to the subjective nature of social phenomena and value judgments of the researcher. Nicolas Diez (Diez Nicolas, J., 1986, p 147) recalls that “objectivity seems to boil down to little more than a certain intersubjective agreement among social scientists.” Along with the above considerations, let us remember the difficulty of holding the variables of the experiments and, in the case of rumor, in which controlling them produces a distorting effect of the natural spontaneous process of the message. Other difficulties mentioned by Ortí in the work of Juan Manuel Delgado and Juan Gutierrez on Qualitative Methods and Techniques of Research in Social Sciences (Delgado, JM & Gutiérrez, J, 1994, p 85-93) are as follows: the process through which the researcher of the social fact becomes an individual influenced by the multiple dimension of what is real; the distinction of at least three levels in social facts: facts, a level that is quantifiable and measurable; significance, which shows consistent messages to their meaning. This second level gives a different meaning depending on the society and culture analyzed; and finally, the level of motivations, generated by impulses and desires that result from the causes of social interaction.

Gonzalo Musitu, a social psychologist who has contributed much in his studies on rumor (Musitu, G., 1978, p 20-21), distinguishes certain advantages and disadvantages from the methodological point of view when performing an experimental laboratory analysis of this message. The former include the ability to control the source of information –a fact that, on the other hand, would detract from spontaneity to the process-; the realization that the communication process has finished; prior establishment of environmental variables; the possibility of quantifying the phases of leveling, stressing and assimilation; and finally, the ability to exercise control over the message at any time of the dissemination. Regarding drawbacks, Musitu highlights the modification of results compared to the natural study of the process; the forced intervention of the researcher in the study process; the risk of simplifying the communication mechanism; the loss of spontaneity that characterizes this message; the risk of not having the cooperation of the analyzed subject and the influence of the emotional elements in the interpretation of the information obtained. Another difficulty that arises when researching this phenomenon is the ability to communicate a phenomenological analysis like this one (Castilla del Pino, C., 1970). This researcher argues that the verification is completed only through communicability and from subjectivity.

The methodology that the author applies to this piece of research combines already mentioned complementary forms of work: the descriptive-analytic method of psychological variables affecting rumor; the comparative method, which allows systematical contrasting of this phenomenon from different contexts and obtaining causal relationships among different realities; and the critical-rational method, which achieves rigorous reflection of the variables under study, their relationships and their effects.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Psychological variables that drive the dissemination of rumor

Psychology studies the internal processes of the individual in their interaction with himself and the environment. The psychological discipline that more closely approaches the study of these messages is social psychology. Early systemized studies about rumor from this scientific specialty emerged in the United States in the shadow of World War II. In that historical context, researchers started from premises which conditioned further studies: rumor was considered a reality-distorting process with serious risks for the various armed factions. (Allport, G. W. & Postman, L., 1967, p 254). Allport and Postman made a distinction between the message with “intent” and the “idle” message and even claimed that “in wartime, rumors undermine the spirit of resistance or moral and threaten national security” (Allport GW & Postman, L ., 1967, p 9-10). These authors set in motion more than thirty experiments in their psychological office. The first conclusion they obtained was the difficulty to trace in detail the chain of transmission of rumor. They also said that 70% of the details of rumor are deleted from the 5th transmission of the message (Allport, G. W. & Postman, L., 1967, p 93-94). Another scholar, Robert Knapp, investigated more than a thousand rumors spread during World War II by the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety (International Encyclopedia of Communications, (Knapp, R., 1989, p 489-490), and his main conclusions were based on identifying three categories according to the underlying psychological motivation: rumors that communicate desires, rumors that express fears and rumors of aggressive motivation.

4.1.1.-A message intended to “be believed”

But the main contribution of Knapp is undoubtedly the identification of the rumor as a “declaration intended to be believed, which is linked to nowadays and is disseminated without official verification” (Rouquette, M. L., 1977, p 124). Moreover, Knapp added that the greatest need for information, interpersonal communication, the unification of the feelings of individuals of a particular group and boredom favor the proliferation of these messages.

4.1.2.- From the Clinics of rumors to the focus of credibility (O.W.I)

With the aim of analyzing and “refining” this kind of messages, the Clinics of Rumors were created in the United States during World War II (G. W. Allport and Postman L., 1967, 47-62). Alongside them, the offices for prevention and suppression of wartime rumor proliferated. The main function of these clinics was the neutralization of “false” news disseminated through the media. These organizations requested the collaboration of the US population to “denounce” those messages that were negative for national security. In this context, the journalist W. G. Gavin created the Bulletin “Herald-Traveler” in Boston from 1942 to late 1943, and he was imitated by more than forty newspapers, magazines and radio programs.

From 1943 on, the atmosphere gradually relaxed on both sides, the danger of defeat decreased and these clinics of rumors ended up losing their sense. Allport and Postman analyzed this phenomenon by addressing the following questions (GW Allport and Postman L., 1967.58-61): to what extent clinics of rumors disseminated false rumors more and their effectiveness in reducing the dissemination of rumors. Alongside these “Offices of truth”, the American Office of War Information -O.W.I. under the command of Leo Roster, dissented from their modus operandi. Roster argued that a rumor is canceled with facts and not with words at the preceding stage to falling into disrepute. The O.W.I. was based on the credibility of the issuer and devoted its time to improve the quality of information and arouse greater confidence in the media and their professionals.

These war and interwar stages were characterized, as far as rumor is concerned, by considering it a very effective tactical weapon of the Roman strategy divide et impera.

4.1.3 Mode of privileged expression

In Europe, Louis Michel Rouquette was the French author who has contributed more to knowledge of this message. He published his doctoral thesis “Rumor Phenomena” at the University of Provence in 1970 and released his book “Rumors” in 1975. The focus of this author is clearly different from that of the American scholars. To him, rumor “is a privileged mode of expression of social thought” (Rouquette, M. L., 1977, 2). This statement breaks with the American concern for the truth or falsity of the message, because what really becomes interesting and valuable is that this message be an individual manifestation that is a reflection of social status.

In our country, Spain, the social psychologist Gonzalo Musitu was the one who devoted a chapter of his book “Social Psychology” to the Psychology of Rumor (1978). Musitu adopts the version of rumor of Allport -a proposition without reliable means of demonstration- but he provides the distinction between rumors caused by a particular event and those intended to bring about facts and effects wherever they occur. He even argues that rumor is not only reduced to cognitive dissonance, which will be explained below, but it can also create it. This author researches the process of rumor in the media, especially in the press and on the radio. Currently we have also to consider the fact to include the Internet, with its different communicative formats (email, web pages, blogs, video blogs, social networks, videos, etc.).

4.1.4.-The range of psychological terms unfolds in relation to rumor

Below we are going to study in depth various psychological factors that shape the reality of rumor. First we will analyze the variables that determine persuasion, which is the framework in which these messages move. Then the author stops in those that demarcate the psychological environment -the individual in the group, the individual’s culture, his vital interests, the prejudice-forming processes, the Intricate complex of fulfilled and unfulfilled desires and the defense mechanisms that come into play in this phenomenon-. We must include in this paper the cognitive processes and, finally, the psychological value of testimony, a communicative concept that contains valuable nuances of analysis.

4.2 Psychological factors of persuasion

The Spanish professor of Social Psychology Francisco Carrera Villar emphasized, in his lectures at the Complutense University of Madrid, Klapper’s work in the decades of 1950s and 1960s on persuasive communication. (Carrera Villar, 1987). The professor said that, in this process, one had to act on predispositions and attitudes. They can be transformed and, first, be reinforced, as the most frequent choice; they can also change in intensity –as a minor change that happens as a second alternative, sporadically-; or they can undergo a real conversion -as a major change in sense and as a less likely third alternative.

Carrera Villar analyzed the psychological determinants of behavior and reminded us that they are all individual factors: cognition, perception, learning, personality, motivation and attitudes. In this paper, we analyze the last two elements, as we consider them key elements in the formation and dissemination of rumors.

The Theory of Motivation (Carrera Villar, 1987) comprises two states: the one that occurs transiently, activation, which allows the individual to “be” in a particular “state”; and the one called Permanent Motivational Disposition, which is influenced by selective targeting and constitutes the “being” of the individual. According to Carrera Villar, DMP or Permanent Motivational Disposition, will allow us to make predictions and, with them, to get to control certain behaviors. Thanks to these dispositions, the issuers of rumor are not only subjects who usually disseminate this kind of messages, but we can also get to predict who “enjoy” doing it and how they behave during the process.

Regarding the behavior of subjects, we should look at Allport’s thesis to understand the following explanatory units. A first key group that includes instincts, motives, feelings, attitudes and habits is established. The second group, which is considered complementary, includes impulses, appetites, desires and needs.

Among all the above terms, it should be clarified that the concept of attitude is the one that has aroused more interest. It can also be expressed with the premise (Expectation x value). In 1972, the theoretician Martin Fishbein proposed the following explanatory formula for this concept (Fishbein, 1975):

Ao = attitude toward an object

Bi = beliefs

Ei = evaluations of those beliefs

N = number of beliefs about the object

Carrera Villar questions the application of this attitudinal model as a strategic persuasive-communicative model and solves it by arguing that if we intend to persuade -that is, modify the attitudes of a particular group- we have to modify the beliefs, modify the evaluations or modify both by contributing a new belief and valuing it positively. This theory of persuasion is very useful to understand rumor, an eminently persuasive message that achieves strengthening the ties of individuals who are part of a particular group.

Carrera Villar rearranges the units mentioned on the previous page in the following blocks:

1. Fundamentally inherited motivational dispositions: instinct, impulse-need-desire-appetite.

2. Fundamentally acquired motivational dispositions: feeling-image-attitude-intention and habit.

Since 1960, this author identified the 4th phase experienced by Psychology applied to the study of consumer behavior as the Sequential Model of Effects. That is, to rigorously know the behavior of individuals, one had to study the sequence Image-Attitude-Intent and Behavior.

In the definition of Persuasive Communication provided by Carrera, the above concepts are included (Carrera Villar, 1987): communication in which the source tries to change -generation of beliefs and attitudes, reinforcement of the existing ones and change or conversion-, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of their receivers.

With regard to rumor, there is no doubt that the sender tries to reinforce preexisting attitudes with his message, either to please the receiver and strengthen his personal relationship with him or to imply that he matches his confident in his beliefs and values.

The behavior of transmission of rumors seems to follow the usual guidelines in this communication process: selection of confidants, mainly verbal behavior -in the case of being transmitted through the Internet, one works with very synthetic texts and in a code that simulates the verbal one in terms of spontaneity-, and reproduction of selective and exponential behavior.

4.3.- Psychological environment that shapes the communicative situation of rumor

The communicative context of rumor is defined by the set of external elements that have a clear influence on its process. The fact that the issuer and the receiver are involved in a group that has its own functioning, its shared values, its interests and its behavior -in short, its intrinsic culture- causes the rumor to be delimited by this environment to a lesser or larger extent. The vital interests of rumor agents will also be studied, as well as the psychological processes of prejudice and the creation and frustration of desires.

4.3.1.-The individual and his best environment, the group

As mentioned in the introduction to this section, the communicative situation of rumor is shaped by the influence of the group over the individual. In this area, Olmsted says that the studies on the influence of the group on the individual show that the latter is more positively stimulated if he is with other individuals than if he is alone (Olmsted, 1972). This stimulating or inhibiting influence will depend on the type of activity carried out by the group and the perception that exists in the individual regarding the group. In general, there is consensus to declare that the individual tends to comply with group regulations, especially if they have been “created” with the participation of the individual. Furthermore, it is considered that the influence of the group on the emotional elements of individuals clearly affects

their personality. Both the content of the message to be transmitted in the form of rumor and the choice of receivers of the group is implicitly determined by each individual of the team. The rumor will have here a cohesive and reinforcing function of the group.

4.3.2. The culture of the group and its gratifications

The term culture is understood in a broad sense as a process of adjustment made by members of the group to propose, amend and consolidate focuses of interest and languages of their own, when making assessments, when adding counterproposals, when contrasting meanings. Each group undergoing this process of adjustment will get a subculture of its own (Olmsted, 1972).

This subculture will undoubtedly condition both topics of interest in the group --also those of rumor- and the people who will deserve contact or those who will not be included in the range of relationships within the group.

What is clear is that the culture of the group gradually consolidates the potential gratifications entailed in behaving according to it, as well as the implied sanctions resulting from denial to follow them.

In this sense, rumor transmission in the group has a clear gratification to the subject, due to both the reinforcement of adherence to it and the group recognition of the participation of each subject in the constructive process of meanings and emotions.

4.3.3 The age of subjects and vital interests

People undergo an evolution throughout their life on their vital interests. The psychologist José Luis Pinillos studies this dynamic projection by analyzing the proposals of Marta Moers in 1953. (Pinillos, 1991).

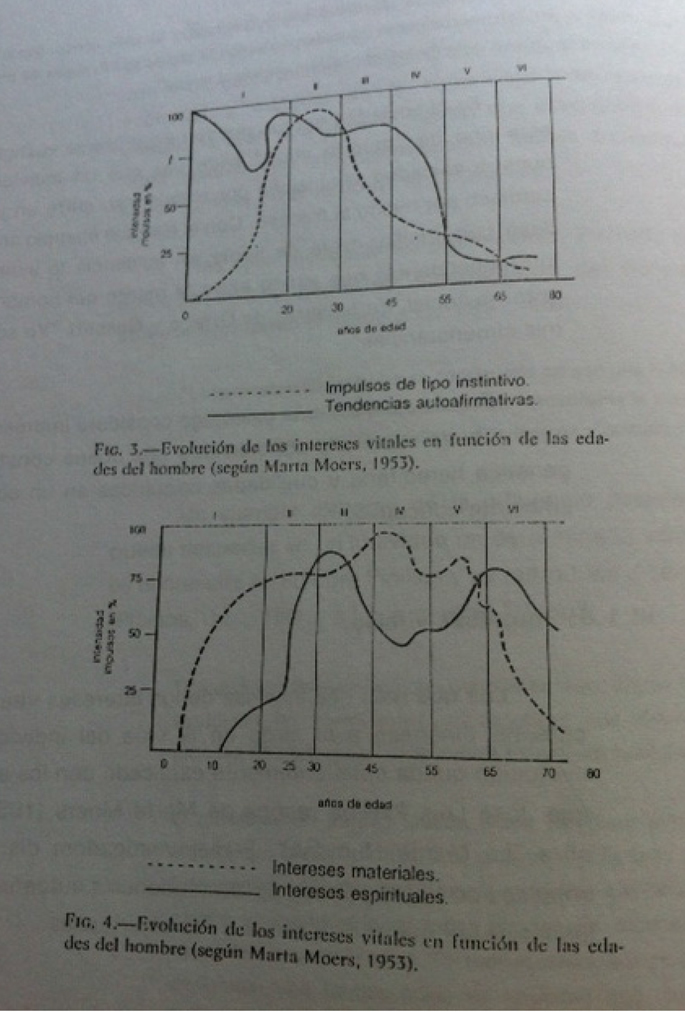

In the chart on the next page, Moers distinguished the instinctive impulses of the self-assertive tendencies of individuals. The curve of the former, the vital instinctual interests, sharply goes down from 30 years, while self-assertive tendencies are maintained at a high level up to 45 years. From this date on, the decline is radical and very fast.

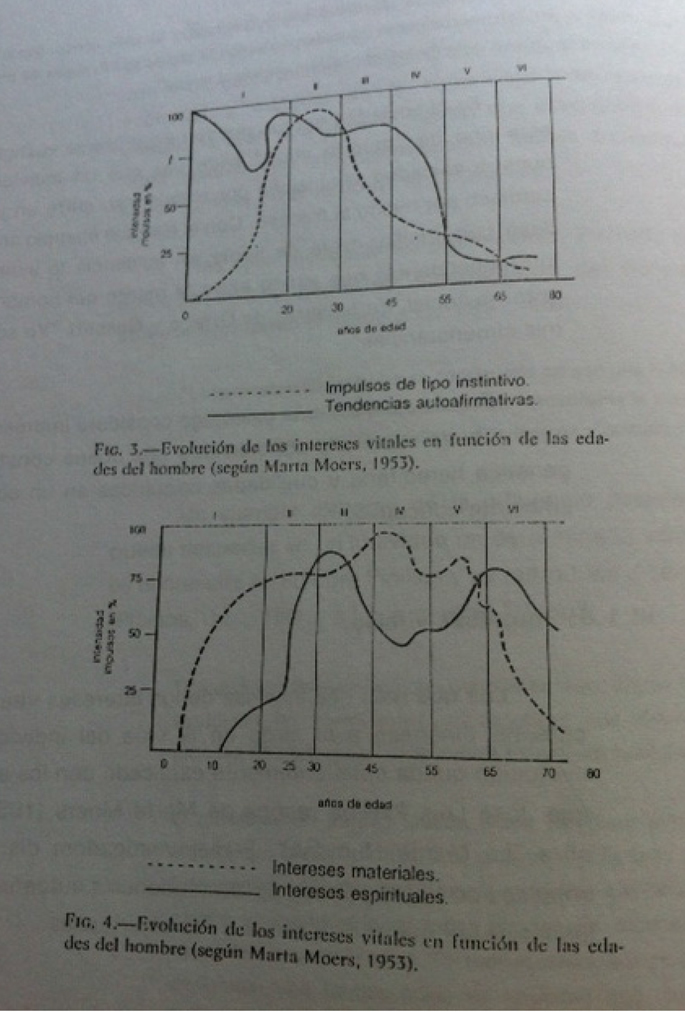

Regarding the curves showing what subjects experience when studying the material interests against the spiritual ones throughout their life, it should be noted that material interests are particularly strong since childhood and remain until about 60 years approximately. From that age on, the interest for what is worldly drastically drops. However, the curve of spiritual interests rises up to 30 years of age, then it softens up to 65 years, and there is a slight decrease above that age.

Figure 1: Evolution of vital interests in terms of the ages of man.

Source: Marta Moers, 1953 (Pinillos, 1991)

The aforementioned vital interests also determine, to some extent, the creation and dissemination of rumors. According to the age of the subjects, they will be more or less prone to be interested in instinctive, self-assertive, material or spiritual contents. Given that rumor is an interesting and ambiguous message, it can be expected that there is some consensus between the issuer and the receivers when identifying relevant contents.

4.3.4 The powerful influence of prejudice

The work that is a reference in the study of prejudice is “The nature of prejudice” by the American researcher Gordon W. Allport in 1962. Then we recalled the words that Allport gathered from Charles Lamb to understand his concept of prejudice (Allport, 1962 : 17): “For my part, bound as I am to earth and chained to the scene of my activities, I confess I feel the human, national and individual differences…In plainer words, I am a bundle of prejudices (made of preferences and aversions), a true slave of sympathy, apathy and antipathy.”

In this statement, it is clear that we are all victims of this process. Allport cites categorization and generalizations as the start and creation of prejudice. The previous judgment resulting from them will become a prejudice if it actively resists any evidence that can disturb it. In all prejudices, there is, on the one hand, a favorable or unfavorable attitude to something and, on the other hand, an excessively generalized belief.

The process of Categorization has the following characteristics (Allport, 1962): the individual categorizes their experiences to guide their daily adjustments in their behavior –the individual typifies an isolated event, places it in a familiar environment and acts accordingly-; It implies maximum simplification; it allows easy identification and perception of reality; It brings together the meaning and feeling or emotion we experience; in most cases, the categories are very resistant to change -the individual resists contrary evidence but has the recourse of the “exception” -.

This cognitive process that mixes emotional, cultural and personal factors occurs on a daily basis. Most life relationships can be done with less effort if we simply live with those who are more like us socially, economically and culturally. So groups tend to remain separated by the same economy of effort, ability to get along and pride for what belongs to one’s own. In this sense, rumor will act as a uniter of individuals within a group by sharing a special message that is not communicated to those who are not part of that group.

This American psychologist argues that prejudice is gradually shaped as the expression of a psychological reaction that occurs within a group against another alien to it. Allport called these groups “Endogroups” and “Exogroups”. The former are reference groups to which the subject is linked and identifies himself, or aims to be psychologically linked. The endogroup is the group to which an individual belongs. The distance between it and the “exogroup” is evident. The latter is the group that will be clearly psychologically distanced from the former. What most interests the author in relation to these two groups is the rejection of exogroups. Allport establishes five kinds of rejecting behavior: verbal rejection, avoiding contact, discrimination, physical attack and extermination. For the study of rumor, verbal rejection is the most revealing one. There are three psychological processes in this process: the inclusion of a prejudice in the conversation, which produces a pleasant “catharsis” in the individual who uses it; naming and belittling the exogroup to consolidate their endogroup, and the reflection of both actors of the communication of their attitudes.

4.3.5 Frustration of desires and defense mechanisms

In Chapter VII of his work “Human Mind” -dedicated to “Man’s desires”, the Spanish psychologist José Luis Pinillos developed the hierarchical nature that characterizes the desires of the individual mentioned by Maslow (Pinillos, 1991). The first needs are physiological, but together with them, there appear superior ones that overlap in a hierarchical order: the need for security, the need for love and affection; the need for self-esteem and the esteem of others –a desire to be asserted against the world and a desire for reputation and prestige-; the need to know; aesthetic needs and, once all of them have been met, the individual experiences the desire to realize himself.

In 1932, A.T. Poffenberg mentioned interpersonal relationships, which ranked sixth among the basic motives of human beings. The tenth place belonged to a group and the desire to be accepted by others. In 1938, H.A. Murray distinguished six groups of interesting needs for this case study: needs associated with inanimate objectives; needs of ambition, power, prestige and desire to do things; needs to exercise, resist or promote power -domination, deference, mimesis, autonomy, spirit of contradiction; needs to cause harm to oneself and to others; needs for affection and socially relevant needs.

Returning to Pinillos, the most outstanding aspect of his theory of human motivation is its plasticity and creative character, so that its needs are not just simple necessary drives but desires subject to the regulation of their will.

When the individual experiences a blockade of his desires because of physical, moral or psychological barriers, then there is frustration -an emotional state that is characterized by disorganization of behavior manifested by confusion, anxiety, frustration, anger, aggressive response, embarrassment, etc-. According to Pinillos, the states of frustration are generated by three kinds of factors: first physical, social, moral obstacles; secondly deficiencies -lack of something that the individual feels he is entitled to. In fact, excessively high levels of aspiration alienated from one’s own abilities produce states of chronic frustration; thirdly, conflicts –which arise due to the existence of several incompatible motives-.

Faced with this frustration, the individual launches several defense mechanisms (Pinillos, 1991: 183-186):

1. Justification, so in many cases the individual just fools himself.

2. Projection, which consists of attributing to the others the undesirable traits that we suffer ourselves.

3. identification, which means taking the good qualities of others as one’s own to be identified with those desirable qualities of others.

4. Reaction, through which the subject hides a certain subject from himself and emphasizes the opposite.

5. Dissociation, when part of behavior splits from the whole and becomes compulsive movement.

6. Excessive theorizing.

7. Repression, which is the negation of undesirable impulses.

8. Substitution, as a more positive mechanism for “egodefense”. It means to replace undesirable objectives of conduct with desirable objectives. There are three types of substitution: sublimation, compensation and overcompensation -Pinillos cites the case of Demosthenes, who not only overcame his initial stuttering but ended up being the most famous orator of his time.

To these contributions from psychology we should add that rumor acts in many cases as a verbal defense mechanism for individuals of a particular group. Labor frustration will be a motivation that causes a unique favorable environment for their dissemination. In the environment of the media, the desires of schadenfreude will be an enabling environment for the creation and dissemination of these messages.

4.4.- The value of testimony in rumor

The American psychologists Allport and Postman were especially concerned with memory and testimony, or the result of the informer as informant (G. W. Allport & Postman, L., 1967, p 15).

In the testimony, the central issue should be binding for the issuer and the receiver, just as is the case with rumor. In addition, the facts to which rumor refers must be covered with some ambiguity. These authors propose the formula (R = i x a), as an expression that the intensity of circulating rumors will vary with the “importance” of the matter for those involved, multiplied by the “ambiguity” of the matter. If i / a are “0”, there will be no rumor.

Knopf said that certain contents of messages tend to recur in the case of rumor, just as in the case of testimony. As an example he cites rumors of “poisoning of the masses” in times of war (International Encyclopedia of Communications, 1989, p 489). The French author Rouquette notes that the study of testimony relates to the process of transmitting the rumor (Rouquette, M. L., 1977, p 12-14): it is close, personal and oral, just as in any other interpersonal communication. Further, he states that rumor is disseminated among subjects committed to the same values ??and beliefs. He even takes into account that it is likely that the degree of commitment of individuals with regard to the group and the content of this particular message may also be linked to the degree of commitment of opinion leaders.

Rouquette argues that the distortion of the message content occurs in any process of information exchange. He also highlights the trend of rumor to lean toward what is negative and it is explained by the author (Rouquette, ML, 1977, p 51-57) with the following reasons: first, due to the psychological disposition of the individual since a series of cognitive processes that determine the capabilities of representation of the universe take place. Second, the individual tends to tilt toward what is negative due to the search for evaluative balance of transmitted contents and due to the informative -specification of the message- and expressive -value of positive and negative reinforcements the individuals of the chain of dissemination expect- dimensions. Negativity comes from rumors intended to communicate something more interesting to the receiver.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The analysis in the previous chapter results in very different conclusions about how the psychological variables affect the creation and dissemination of rumor. From the contributions of Social Psychology, rumor is drawn as a form of polyhedral and spontaneous communication that is very difficult to control to study it.

The theses of the Spanish psychologist Carrera Villar stand out from the study of persuasion, these theses comprise persuasion as a reinforcement or modification of the attitudes of a particular receiver, for which the beliefs of individuals and their evaluations on them must be modified. Rumor is an eminently persuasive message, due to the high degree of involvement that it implies for the issuer and its receivers. The predominant role in this process will be to reinforce the preexisting attitudes of these agents of communication. In addition, permanent motivational disposition will make it possible to predict verbal behavior of each link in the chain. Regarding the psychological context surrounding the rumor, the theories of Olmsted about the group’s influence on individuals have been emphasized; the relevance of the culture that creates the group under the mechanism of gratifications and penalties resulting from compliance or noncompliance with the rules agreed therein; the importance of the age variable in determining the vital interests affecting the content of the messages that are exchanged; the powerful influence of prejudices, which, in the case of rumor, allow the individual to reinforce their link to the “endogroup” and reject the “exogroup”; and finally, the identification of the desires and defense mechanisms. In this last aspect, we must include the important function of rumor to strengthen interpersonal relationships among individuals, one of the most important desires, and the use of rumor as a defense mechanism against frustration or blockade of certain psychological and social needs.

Throughout the document, we have reviewed the evolution of this “elusive” message throughout the 20th and 21st centuries under the prism of Social Psychology. From the American researchers of the Second World War to present day, rumor has gone from being considered a “distorting” process to being the “statement intended to be believed, the dissemination of which has no official verification” (Knapp, 1989) passing through “a privileged mode of expression of social thought “(Rouquette, 1977).

Currently, media and interpersonal and corporate communication is undergoing a process of revolutionary change with the advent of the Internet and social networks. Today, controlling this spontaneous process of expression becomes unworkable because it is an extra-official message, but its effects require the scientific community, professionals and researchers of communication to continue approaching its reality in order to analyze and foresee it. This paper is only a first step in the research line of analysis of this captivating message.

6. REFERENCES

1. Allport G. W. & Postman, L. (1946-7). An analysis of Rumor. Public Opinion Quarterly, 10, 501-517.

2. Allport, G.W. (1962). La naturaleza del prejuicio. Buenos Aires: Ed. Universidad de B. A.

3. Allport G.W. & Postman, L. (1967). Psicología del Rumor. Buenos Aires: Ed. Psique.

4. Carrera Villar, F (1987) Apuntes del Curso de licenciatura “Psicología aplicada y métodos de investigación”. Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Facultad de Ciencias de la Información.

5. Castilla del Pino, C. (1969) La Incomunicación. Córdoba: Ed. Península, Nueva colección ibérica.

6. Castells, L. (1999). El rumor de lo cotidiano. Estudios sobre el País Vasco.

7. Delgado, J.M. & Gutiérrez, J. (1994). Métodos y Técnicas Cualitativas de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales. Madrid: Ed Síntesis.

8. Díaz, M. J., Valdehita, S. R., García, J. M., & Moreno, L. L. (2006). La comunicación interna como herramienta estratégica al servicio de las organizaciones. EduPsykhé: Revista de psicología y psicopedagogía, 5(1), 3-32.

9. Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An introduction to Theory and Research. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley

10. Goffman, E. (1987). La presentación de la persona en la vida cotidiana. Buenos Aires: Ed. Amorrortu.

11. Guadalupe, G. A., & García, A. L. G. (2009). Del” Word-of-mouth” al marketing viral: aspectos claves de la comunicación a través de redes sociales. Comunicación y hombre: revista interdisciplinar de ciencias de la comunicación y humanidades, 5, 41-51.

12. Gurmandi, A., & Calciano, A. L. (2012). Comunicación Interna-Gestión de la comunicación informal en las organizaciones. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Belgrano

13. Gutiérrez Ballarín, R. (1986) Rumor y Manipulación informativa: eficacia del mismo. Tesis doctoral, UCM, Madrid. Dirigida por el Prof. Dr. Pedro Orive Riva. Dpto. Estructura de la Información, Facultad de CC. de la Información, Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

14. Hermida Lloret, J.M. (1993). La Estrategia de la mentira: manipulación y engaño de la opinión pública. De los grandes escándalos financieros al caso Bosé. Madrid: Editorial Temas de Hoy.

15. Kapferer, J-N. (1989). Rumores. El medio de difusión más antiguo del mundo. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores.

16. Kapferer, J-N. (1990). Rumors: uses, interpretations and images. France: transaction Books.

17. Lippmann, W. (1997). Public Opinion. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

18. Mazo, M. E. (1997). El rumor y su influencia en la cultura de las organizaciones (Doctoral dissertation, Tesis doctoral, Facultad de CC. de la Información, Universidad Complutense de Madrid).

19. Mazo, M. E. (2015). El rumor en las organizaciones desde una aproximación multidisciplinar. Opción, 31(3), 797-819.

20. Moret, J., & Arcila, C. (2011). Comunicación interna e informal en las organizaciones. Temas de Comunicación, (22), 7-22.

21. Musitu, G. (1978). Psicología Social. Valencia: N.L.

22. Office of War Information, Inteligent report. (1942). Rumors in War Time. O.W.I.

23. Olmsted, M.S. (1972). El Pequeño Grupo. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós.

24. Pinillos, J.L. (1991). La mente humana. Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy

25. Pizarroso Quintero, A. (1990). Historia de la Propaganda. Notas para una historia de la propaganda política y de guerra. Madrid: Eudema.

26. Rouquette, M.L. (1977). Los rumores. Buenos Aires: Ed. El Ateneo.

27. Rouquette, M.L. (1979). Les phénomenes de rumeurs. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Provenza.

28. The Annenberg School of Communications, University of Pennsylvania, (1989). International Encyclopedia of Communications. New York: Oxford University Press, 4 t.

AUTHOR

Maria Elena Mazo Salmerón

PhD in Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid and professor of Theory of Communication and Information at the Faculty of Humanities and Communication Sciences of San Pablo CEU Universidad in Madrid. She combines her teaching undergraduates and graduates with research of communication processes in multidisciplinary working groups of San Pablo CEU University. She also addresses consulting in strategic communication for national and international entities. She has specialized in Internal Communication and its influence on the corporate culture of institutions and companies- she is the author of a doctoral thesis focused on Rumor and its communicative effects within organizations. She participates as a speaker in international congresses, she is a lecturer and author of articles and publications on Communication, including, as a last research line, the communicative aspects that make up the Corporate Responsibility of organizations.

ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2978-5521

Researcher ID: B-8962-2