10.15198/seeci.2016.39.105-126

RESEARCH

HOW TO ANALYZE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF COMMUNICATION DEPARTMENTS IN HOSPITALS AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES TO CITIZENS? METHODOLOGICAL EXAMPLE

¿CÓMO ANALIZAR LAS CARACTERÍSTICAS DE LOS DEPARTAMENTOS DE COMUNICACIÓN EN LOS HOSPITALES Y SUS CONSECUENCIAS EN EL CIUDADANO? EJEMPLO METODOLÓGICO

Lorena Busto-Salinas1 PhD in Communication, is a professor of international communication at the Pontifical University of Comillas. His research revolves around public relations, health communication, disclosure of assets, corporate communication and media analysis.

1University of Burgos. Spain

ABSTRACT

The article presents the methodology used to study the quality of public relations in hospitals, as well as to determine if the number of communication departments has an influence on the characteristics of this practice and on the information released in the press, and if there are any differences between the public and private sector and between internal departments and external companies. In addition, it has been studied if hospital communication influences citizens to participate in news stories and if it affects their assessment and satisfaction with the healthcare system.

Two communities of Spain (Castilla y Leon and Galicia) with similar social, economic and healthcare system characteristics, but with a different communicative structure, have been chosen as objects of study. Personal interviews and a survey to communication officers in each hospital have been conducted, as well as a press analysis, a study of participation of citizens in internet news and an analysis of the assessment of and satisfaction with sanitation. No evidence has been found supporting the idea that the communicative competence produces better public relations. However, it has been noted that the quality of news stories is higher in places with a greater number of press offices. In addition, citizens of these regions vote and share information more often, they consider health and sanitation issues to be more important, they have a greater assessment of the public healthcare system and would choose this ownership over private centers.

KEYWORDS: public relations, health communication, press analysis, quantitative analysis, qualitative analyses, consumer behavior, health

Recibido: 20/11/2015

Aceptado: 10/02/2016

Correspondence: Lorena Busto Salinas, PhD in Communication, is a professor of international communication at the Pontifical University of Comillas.

Correo: lbusto@ubu.es

1. INTRODUCTION

The health and sanitation issues are becoming of greater significance for the citizens, as shown by various opinion surveys (Cangelosi; Ranelli; Markham, 2009; Castiel; Alvarez-Dardet, 2005; Centre for Sociological Research, 2012; Len-Rios ; Hinnant; Park, 2009; Pew Research Center, 2004; Weaver-Lariscy; Avery; Sohn, 2010). Patients now report more about their needs and are no longer subject only to instructions from their doctor, as they take a more active role in decisions related to their health (Del-Pozo-Irribarría; Ferreras-Oleffe, 2011; Freberg; Palenchar, Veil, 2013; Gbadeyan, 2010; Thomas, 2005; Wrenn, 2002). The increase in documents on this subject, as well as information sources, has been able to contribute (Amador-Romero, 2004; Avery et al, 2010; Brodie, Glynn, Van Durme, 2002; Eggener, 1998; Observatory of Scientific Communication, 2008; Roessler, 2007; Viswanath, 2006). And the point is that the news appearing in the mass media have multiplied in recent years, although these are not the only source for information on health issues. Today, people learn about medicine and health through family and friends, advertising, TV shows, websites, forums, blogs, social networks, brochures, etc (Amador-Romero., 2004; Avery et al, 2010 ; Freberg et al, 2013;. Jiménez-Pernett et al, 2009; Kreps, Bonaguro, Query, 1998; Lupiáñez-Villanueva, 2009; Roessler, 2007; Wrenn, 2002).

Consequently, communication in healthcare is increasingly necessary (Anand & Chakravarti, 1981; Costa Sánchez, 2012; Diaz, 2011; Henderson, 2005; Hibbard, Stockard, & Tusler, 2005; Keller et al, 2014.; Kirdar, 2007, Meath, 2006, Menéndez Prieto & Vadillo Olmo, 2010; Pham, Coughlan, & O’Malley, 2006; Scott, Vojir, Jones, & Moore, 2005; Lariscy Springston & Weaver, 2005). The public of the centers dedicated to health is no longer just the patient, but other groups such as employees, family members and visitors, community groups, etc., are also relevant (Anand; Chakravarti, 1981; Balima , 2006; Diaz, 2011; Gordon, Kelly, 1999; Gudykunst; Kim, 1992; Guy et al, 2007; Igartua-Perosanz, 2006; Ivanov; Sims; Parker, 2013; Kirdar, 2007; Kreps, Kunimoto, 1994; Kreps 2008; Kurtz, 1969; Springston, Champion, 2004; Weaver-Lariscy; Springston, 2007; Youmans; Schillinger, 2003). This is particularly important in the case of specialized care centers, given their great human and technological capacity, where a wealth of information both on health-related dissemination and hospital activity can be provided. Communication departments of these centers are a link between the organization and its various publics. Among its tasks is to know and meet the needs of citizens, convey reliable information, liaising with journalists and the scientific community, complete or correct erroneous information, etc.

2. OBJECTIVES

However, so far there are no studies that specifically show the characteristics of the communication departments that exist in health centers or the benefits they bring both with the information disseminated by the mass media and the consequences for the population. Indeed, these are the main objectives of the doctoral thesis entitled “Health communication and its implications for attitudes and accessible information to citizens. Comparative study of Castilla y Leon and Galicia”, defended by the author of this article on the University of Burgos in 2015, the methodology of which is outlined in this article.

Before establishing a working method, a series of hypotheses have been designed. These assumptions are about the presence and characteristics of communication departments in hospitals and the consequences that these have on both media reports and perceptions of citizens about medical issues. Both at the general level and facing the two communities studied, this study is structured according to the following hypotheses:

H1. Because communicative competence, when many hospitals in a region have communication departments, the public relations that are adopted should be more excellent.

H2. The presence of communication departments in hospitals should have an impact on the number and quality of information on health published by the media in the region.

H3. The citizens of the areas with communication departments in most hospitals must be more active in consuming health information in the sense that they comment more frequently about these topics, value and share them with their acquaintances.

H4. The citizens of the areas where there are communication departments should have a better appreciation and a higher degree of satisfaction as regards the health system.

H5. Communication departments of public and private hospitals may have differences in terms of public interest in the use of more or less traditional methods and new communication actions.

H6. Hospitals managed by external media companies would exert more excellent public relations than those with one or two employees on the payroll due to the diversity of public relations staff

3. METHODOLOGY

To meet the hypotheses made, we have selected two regions of Spain with similar social, economic and health characteristics but with a different communication structure. Specifically, we compared Castilla y Leon and Galicia. For example, in the community of Castilla there are 2,765,940 people and the in the Galician community 2,519,875 (National Statistics Institute (INE), 2013). The proportion of women and men and the age of the population are also very similar (National Statistics Institute (INE), 2013). The GDP of the region of Castilla in 2012 is 21,994 euros per inhabitant and in Galicia it is 20,330 (National Statistics Institute (INE), 2012). As for health care, both territories provide very similar figures of equipment, even the number of hospitals in both areas in 2012 is exactly the same: 37. The situation regarding functional dependency does not offer too disparate differences, neither does the number of beds. As for operating rooms in 2012, Galicia records 10 per 100,000 inhabitants, Castilla y Leon, 9. The proportion of operating rooms in public centers compared to those found in private centers is very similar in both regions. Galicia, with 198 public and 74 private has 2.68 times more public than private. Castilla y Leon offers an almost identical ratio: 157 public and 60 private with a multiplication rate of 2.62 (Institute for Health Information, 2009, 2013a).

However, the communication structure is very uneven. Castilla y León centralizes the communication of all public hospitals in the communications department of the Ministry of Health of the regional government, while in Galicia, apart from having a service of this kind in the regional administration, there are cabinets of this type in every major hospital. Thus, in the first region, there are seven communication departments (adding both public and private), while in the second there are fifteen.

The theoretical framework used is that of public relations, focusing on models, roles, defining specific objectives, participation in strategic plans, personal influence, public, tools, stages of a public relations program, etc.

The empirical part focuses on three different tools. On the one hand, there have been personal communication managers of hospitals in the two regions in order to obtain qualitative information about their history, work, independence, improvements to be enforced, etc. On the other hand, these same people have completed a survey with quantitative data to help measure the use of public relations in the hospital setting. Also, a press analysis has been conducted in order to learn whether there are differences in the presentation of health issues in the media according to the communication features of each region. Finally, several surveys have been consulted about the interest of the public on these issues and their satisfaction with the functioning of the health system.

Thus, the empirical part of the thesis combines both qualitative and quantitative paradigms. The first approach aims to create generalizable trends and their data are liable to statistical analysis (Lozano Rendón, 2007). By contrast, the second helps contextualize and frame hypotheses, which cannot be done from a purely quantitative viewpoint (Wimmer and Dominick, 1996, p. 148).

With the union of the two methodologies we achieved the phenomenon of triangulation, a method that is becoming a common scheme in companies and universities (Casetti and Di Chio, 1999, p. 333), since it compensates for the weaknesses of a method with a different method and thus the “most reliable and entirely satisfactory” results are attained (Elias, 2000, p. 38). It is the most advanced stage of integrating various methodologies (complementation, combination and triangulation), since the results of all methodologies converge to reach the same conclusions (Breijo Rodriguez, 2009). a methodological triangulation occurs when at least two research techniques (can be qualitative and quantitative) or two different methodologies are used to understand and analyze the same object. Below is a detailed analysis of each analysis used in research.

3.1. Qualitative analysis: interviews with those responsible for communication in hospitals

In an effort to know the characteristics of communication in the hospitals of Castilla y Leon and Galicia, we conducted in-depth interviews with those responsible for communication in these centers, both public and private. To this end, the National Catalogue of Hospitals (Ministry of Health, 2013) was consulted in order to know the specialized care centers in each area.

Those responsible for communication in public hospitals were located via the communication departments of the Ministry of Health of each community. Meanwhile, those in charge of communication in private centers were found through the information sections of each hospital, which resulted in consultation of employees on the payroll or external companies, as appropriate. Previously, a website with information on the doctoral thesis was created for communication managers to know in more detail the characteristics of the study. On this platform, an overview, objectives, structure, abbreviated curriculum vitae of the directors and the author and contact details were included. When requesting the participation of those responsible for communication, they were explained by phone the particularities of the doctoral thesis and they were emailed a work summary and a link to the website.

Adding public and private hospitals, for the 37 hospitals existing in each region Castilla y León has 7 communication departments (one public and six private) and Galicia 15 (8 public and 7 private). Out of these 22 officers responsible for communications, 19 have agreed to collaborate. Divided by community and ownership, in Castilla y León three private and one public have participated, while in Galicia there have been 8 from public hospitals and 7 from private hospitals. The meetings took place in Galicia during the months of May and June 2013, while in Castilla y León, the meetings occurred in March 2014. As those belonging to the National Health System in Castilla y León do not have a person dedicated to communication but centralize all this work in the communications department of the Ministry of Health, the head of this service was interviewed.

3.1.1. Content of the interviews

At the meetings, issues such as completed studies, professional career, their day to day, the main kinds of public and the actions taken with each of them, liberty or pressures, etc. were dealt with The meetings lasted from 45 minutes to an hour and a half, depending on the availability of respondents and development of the interviews. The general questions of the talk, and from which new ones could arise, are as follows:

1. Professional career.

2. Day to day in the hospital.

3. Main kinds of public, namely: patients, relatives and visitors, employees, political and institutional agents, investors or shareholders (if any), the media, general public ...

4. How do you communicate with each audience?

5. Any new communicative action?

6. Schedule: who does the communications department depend on?

7. Does the person who governs the community or the manager of the hospital have any influence? Examples.

8. Do you know your budget? Is it a major obstacle?

9. How much freedom do you have to perform the actions (content, budget, ideology ...)?

10. What are the pressures that have to endure (right to privacy, right to information ...)?

11. What are the differences between managing communication within the institution or through an external firm? Which one do you consider to be better?

12. Benefits of a communications department for the hospital and healthcare in general.

13. Communicative errors made (both in the hospital and in the field of health in general).

14. Improvements you would make (both in the hospital and in general).

15. Why are these actions not carried out (both in the hospital and in general)?

For the analysis of this part, their views are grouped by region and subject and verbatim statements and real examples provided by workers have been added. In some cases, or by express request of the respondents or on the own initiative of the researcher, quotations are not attributed to a specific character due to the impact they could have on their environment.

3.2. Quantitative analysis: surveys to those responsible for communication in hospitals

Since personal interviews provide only qualitative assessments, a questionnaire has been designed with questions concerning public relations and it has been handed out to those responsible for communication in hospitals for them to fill it out. Thus, quantitative and statistically analyzable data on the following aspects are obtained: models, roles, the model of personal influence, communication plan, participation in strategic plans, target audiences, the phases of a public relations program, types of assessment and preparation for crisis.

In most cases, they filled it out the same day of the interview and, in a few cases and due to the limited time available to talk to the researcher, they filled it out later through an online server. There was a person who, claiming lack of time, did not fill out the questionnaire either in person or online.

Some questions have been drafted by the researcher of this thesis and others have been adapted from other related pieces of research. Four kinds of data collection have been chosen. Most of them are questions of Likert scale from 1 to 5, where one equals “strongly disagree” and five means “strongly agree”. There are also several verification tables or checkboxes for which the respondent should only select, out of fixed options, the variables with which he agrees. In addition, some questions are answered or “yes or no” and, in a few cases, the answer must be selected from a dropdown list.

Questions to determine the use of the four models of J. E. Grunig (1984) have been adapted from the questionnaire of the Excellence Study, also used in other pieces of research, such as those of Gordon and Kelly (1999) and Xifra (2008). Thus, four ideas for each studied model are offered, for a total of 16 questions. It has also been decided to study the presence of persuasive symmetrical bidirectional proposed by José Luis Arceo Vacas (2006), so other four additional statements have been drafted to determine their use, the figure finally being 20, they can be answered in a scale of 1 to 5.

As for the roles of public relations that are used, it has taken into account the selection initially made by Kelly (1994) and later adapted to other pieces of research, such as that by Gordon and Kelly (1999). This piece of research reduced tje 16 questions of J. E. Grunig (1992) to eight, four per each studied role. In this case, a Likert scale has also been used.

The following series of statements in the survey is about defining and achieving specific goals and about participation in strategic plans. Those relating to the first issue have been made by the author of this paper, while those belonging to the second aspect have been taken from Gordon and Kelly (1999). More specifically, the two ideas that have been selected from these researchers are: the strategic planning team usually consults the communications department and a member of the department is part of the strategic team of the hospital. Except for an answer “yes or no”, the rest are designed by scale.

To determine the personal influence model proposed by Sriramesh (1991), we used the questionnaire used by Xifra (2008) in his analysis of the models of public relations in Catalonia, which includes the following: I have good relationships with other employees, I have good relationships with people outside my organization, social relations are one of my most important activities and I try benefits (food, gifts) to gain influence with my personal contacts. Respondents could answer on a scale from 1 ( “strongly disagree”) to 5 ( “strongly agree”).

Having established the importance that those responsible for communication give to social relations, we have tried to see what audience is the most important to the department. To this end, we selected a number of groups that a priori encompasses all audiences in hospitals. These are: patients, relatives and visitors, employees, political and institutional agents, investors or shareholders (if any), the media and the population in general. From this list, respondents were asked to choose, from 1-5, the level of importance given to each group.

Since strategic management of public relations requires specific planning, we have tried to determine the degree of importance that is granted to the different phases by using a scale. From the existing models, we have selected the version of Hainsworth and Wilson (1992) and Guth and Marsh (2000), which divide the stages of a campaign into: research, planning, reporting and evaluation.

To find the tools used by communication departments at each stage, we have set up verification tables or checkboxes with an extensive list of options. Also, the possibility to answer these questions with a box free filling of offered. As for the research phase, many of the tactics have been selected from the manual Public Relations: Strategies and tactics, by Wilcox, Cameron and Xifra (2007), while others have been made by the author of this paper. In terms of planning, all come from the aforementioned manual. Given the number of tools available to implement the phase of reporting and the audiences that can be targeted, the verification tables have been divided according to the major audience for which they are used: employees, patients and visitors, media and population. So both for this section and for evaluation, some options by Wilcox, Cameron and Xifra (2007), Xifra (2007), Castillo Esparcia (2006), Rojas (2008), Palencia-Lefler (2011 ) and others made by the author of this paper have been consulted and taken.

Also, the different kinds of measurement have been studied, as Wilcox, Cameron and Xifra (2007) divide them: production, exhibition, opinion and public attitudes and actions and behaviors of the public. To do this, we used a Likert scale. Subsequently, those responsible for communication have been asked if they have a crisis plan, how often it is reviewed and implemented (these two questions with fixed answers from a drop-down list) and if there is a default team of people for potential conflicts. Finally, we have asked them how important they consider their department is to the hospital and how satisfied they are with the communication activities carried out by the center on a scale of 1-5.

Once the surveys have been completed, the answers have been introduced in the SPSS statistical program and there have been various analyzes, especially descriptive and frequency, the results being divided according to the initial hypotheses. We have also implemented various statistical tests such as chi-square and Student’s t-test, to find statistically significant relations. Significance was set at equal to or less than 0.05. This way, we can determine that there is a statistical relationship and that the results are not fruit of chance. Thus, we analyzed the difference in answers between Castilla y León and Galicia, between the public and private spheres and between internal and external cabinets.

3.3. Press analysis: measuring the exhibition

To study the impact of communication departments on the number and quality of information on health published by the media, we proceeded to analyze the news published by newspapers in each community. To do this, we have used the Iconoce tool, a database of media with an archive service that allows introspective search for news on the Internet since 2001 (Iconoce, 2014). The study period was limited to 2012 and we have selected all regional, provincial and local general newspapers in both communities that maintain open access to that space. Thus, the websites consulted in each community amount to 15, for a total of 30 analyzed newspapers.

Since few electronic journals have a regular section dedicated to health, the news that compose the study sample were obtained by searching through multiple keywords. In the case of Castilla and Leon, the chosen words were: sanitation, health, medicine, physician, hospital, clinic, pharmacy, pharmacist, disease and Sacyl. To find news in Galicia, the Galician translation of the terms in Spanish in those cases where they are different has been added and the Galician Health Service (Sergas), so that the information have been sought through the following chain: sanitation, health, sanidade, saúde, medicine, physician, hospital, clinic, pharmacy, pharmacist, disease, enfermidade and Sergas.

3.3.1. Sampling and error margin

Since Iconoce offers only 200 results at most in one search and, therefore, it is very difficult to determine the number of news published by the media on health over a long period of time, we proceeded to perform sampling to calculate the news disseminated by the different media in a year, in particular in 2012. To this end, we selected a random day of each of the twelve months of the year, trying that they were in different weeks and weekdays. We started with a Tuesday in the first week of January, we have continued with Wednesday in the second week of February and have continued with a Thursday in the third week of March and so on.

The total number of collected news in the 12 days that make up the sample amounted to 713 842 Castilla y Leon and 842 Galicia, or what is the same: 59 daily news in the media in the former region and 70 in the latter.

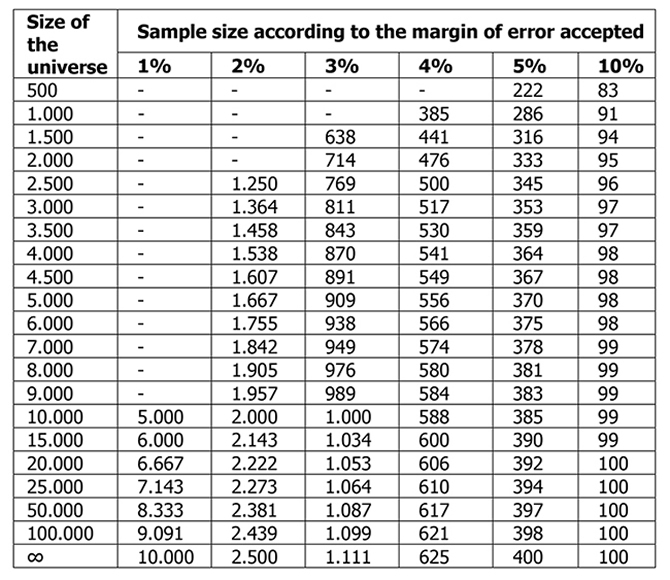

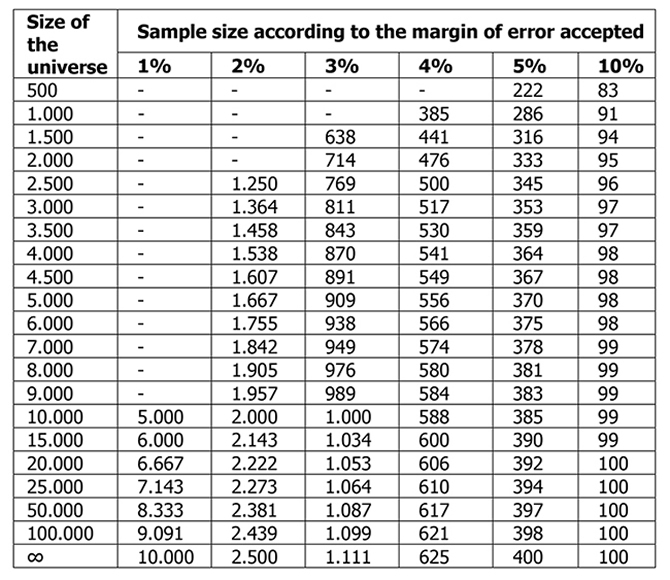

Thus, sampling determines that in Castilla y León there are 21,687 health news in a year and 25.611 in Galicia. To get a sample that is representative in terms of the universe of study, we examined sample size according to the size of the universe and desired error margin.

Table 1. Sample size according to different error margins and size of the universe.

Source: Arkin and Colton, Tables for Statisticians. Taken from J. Bugeda, Technical Manual for Social Research. I.E.P. Madrid, 1970.

To obtain an error margin of 5% and for the sample to be significant, from 392 to 394 news in Castilla y Leon and from 394 and to in Galicia have to be examined. To round off, we decided to study 400 in each territory. Broadly speaking, the elements that have been studied from the media analysis are: number of news, section, authors, location, gender, size, audiovisual, theme, neutrality, reporting organizations, contrast, file, second source, links and interaction of the reader.

The results were entered into the SPSS statistical program and there have been various analyses such as frequencies, descriptive, contingency tables, chi-square, Student’s t test, etc. The significance in statistical tests was set at equal to or less than 0.05. This way, we can determine that there is a statistical relationship and that the results are not fruit of chance.

3.4. Measuring public opinion and attitude

In order to know the opinion and attitude of the population as regards public health, we has made use of the Health Barometer published annually by the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, whose latest results according to the date of research are for the 2013 exercise. This is a report containing the assessment of the public on the operation of the Spanish health system and satisfaction with the quality of services, in both cases with reference to the public domain. It is the only one that divides the results by regions and allows comparison between the two parts of the study. The total sample consists of 7,800 interviews conducted in person at the homes of 237 municipalities of the 17 communities and two autonomous cities (Institute for Health Information, 2013b), using a structured questionnaire. On the whole, it has a sampling error of ± 1.13% for a confidence level of 95.5%. In Castilla y Leon 423 interviews were conducted for the last number and, in Galicia, 441 (Institute for Health Information, 2013c).

This report has analyzed two areas in which public relations can have implication: opinions and attitudes, and the actions and behaviors of the public. To find the first aspect, we consulted the interest of public health for the residents in Castilla-Leon and Galicia and their assessment of the health system and their satisfaction with different aspects. On the contrary, to determine the actions and behaviors of citizens, we have used measurements on the choice of hospitals and the reasons for such determination. This latest analysis divided the elections into public and private dependence centers. Thus, the results of Castilla y Leon and Galicia are opposed to check for significant differences.

4. DISCUSSION

The use of several methods for analysis allows us to obtain more reliable results than what a single methodology would have offered. The analysis of personal interviews and the surveys does not show any serious discrepancies and the analysis of both methodologies provides similar results. Thus, we could verify that the use of public relations is very similar in the two studied communities. In both cases, the use of roles and models is practically the same. The communications in the two territories also have the same possibility of being part of the strategic team and having a default plan and team to face possible crises. The main kinds of public are the same in the two territories, though their order changes slightly. In the two regions, more attention is paid to external communication, mostly the one that is pipelined through the media, the internal one being pending. Likewise, they use similar tools in the different stages of a public relations program, though Galicians use a higher number in the communication phase. The only statistically significant difference has been found in Castilla y Leon, whose communicators give more importance to personal relations.

After the personal interviews and the surveys to those responsible for communication in hospitals, we observed that the highest difference in the use of public relations is found according to the ownership of the center. Thus, public centers usually pay more attention to the media and the political and institutional agents than to private ones. The latter, in turn, are more focused in personal relations, they are more liable to being part of the strategic coalition and have a default plan and team for possible crises. They are also more aware of the different stages of the public relations program and evaluate their actions more frequently than the workers of the public sector. Likewise, they have a wider range of new activities, both as regards new technologies and concerning the organization of events.

External companies tend to be part of the strategic team of plans more often than the persons working internally. Likewise, they usually follow a communication plan and pay more attention to the different phases of a public relations program, with more difference in planning and evaluation. Thus, they usually follow objectives and use more tools and different theoretical approaches to analyze the success of the communicative efforts.

The number of news published by newspapers in each community regarding health is practically identical. The use of audiovisual aids, links as well as data from archive, contrast and second sources does not show any significant differences either. However, in Galicia, where there are more communication departments about these issues, news are usually inserted more frequently in the local section, the new things are framed more often in places belonging to the region and it is more probable that the texts be made by the editors of the newspaper instead than by communication agencies. Besides, they usually disseminate more explanatory and interpretive compositions, beyond the mere information. As for hospitals, they are more recurrent sources of information in Galicia than in Castilla y León, both in the informational and non-informational genders.

Though the readers from Castilla and León comment on health news appearing in the internet newspapers a little more frequently than those from Galicia, the latter go ahead the former as regards frequency and number of votes. They also recommend the news with more regularity in the social network Facebook and share more often and with a larger number the news in Twitter. The first and the two last relations are, in fact, statistically significant.

The Galician citizens consider public health to be a more transcending issue than the citizens from Castilla y León. Likewise, they value more the public system, a view that, in addition, improves in the course of years. Therefore, more Galicians would choose public centers than citizens from Castilla y León and they state more reasons to justify it. However, where it comes to satisfaction relating specialized medical care, the perception of those citizens who went to a specialist physician is more positive in Castilla y León, in spite of the fact that to those who went to a hospital. It is higher in Galicia. As for general satisfaction with the public health system, the citizens from Castilla y León go ahead of Galicians.

Given the results that have been obtained, the starting hypotheses can be answered. Out of the six proposals, two have been accepted, one has been refuted and the three remaining ones have been partially accepted.

H1. Due to communicative competence, when a great deal of hospitals in a region have communication departments, the public relations that are enforced should be more excellent: refuted.

H2. The presence of communication departments in hospitals should have a repercussion on the number and quality of information on health published by the media in the region: partially accepted.

H3. The citizens of the areas having communication departments in most hospitals must be more active in consuming health-related information, in the sense that they comment on these issues more frequently, value them and share them with their acquaintances: partially accepted.

H4. The citizens of the areas where there are more communication departments should value more and be more satisfied with the health system: partially accepted.

H5. The communication departments in public and private hospitals can have differences as regards their interest for public opinion, in the use of more or less traditional methods and in the new communication actions: accepted.

H6. The hospitals managed by external communication companies would have more excellent public relations than those that have one or two employees on the payroll due to the diversity of personnel: accepted

5. CONCLUSIONS

Using triangulation in the analysis of communication that takes place from several entities, in this case health-related ones, gets beneficial results, since it allows us to counteract the weaknesses of each method, offering more reliable results. In this case, we have compared the qualitative data collected during personal interviews with quantitative information derived from the survey, with media analysis and the analysis of public opinion and behavior. As a result, it was possible to draw several conclusions which summarize the contributions of this thesis to the field of public relations and health communication:

1. There is no evidence that there are excellent public relations in a territory in the field of health as a result of a communicative competence.

2. The biggest difference in the use of public relations has been detected by ownership of the hospital. Communication managers in private centers tend to make better use of this discipline than those in public centers.

3. In general, external communication companies responsible for communication in a hospital make a better use of public relations than the people working as internal employees in the center.

4. The number of news media published on health is unrelated to the amount of communication departments that exist in a given territory. That is, interest in health by journalists does not depend on the number of communication departments, since they can get data from other sources.

5. Although the number of stories in newspapers is similar regardless of communication departments in an area, the quality of information is higher in places with a larger number of press offices.

6. In areas with a higher amount of communication departments dedicated to health, citizens vote more often and share more Internet information relating to health, though they do not comment on it more frequently.

7. Citizens in areas with a larger number of communication departments in the health field consider it more important than those with fewer cabinets of this sort.

8. In regions with more public hospitals with communication departments, citizens have a greater appreciation of public health and would choose this ownership before due to a larger number of reasons.

9. Regarding satisfaction with the public health system, there is no difference between citizens regardless of how many communication departments exist in an area.

REFERENCES

1. Amador-Romero, FJ (2004). Medios de comunicación y opinión pública sanitaria. Atención Primaria, 33(2):95–98. doi: 10.1157/13057251

2. Anand RC, Chakravarti A (1981). Public Relations in Hospital. Health and Population (Perspectives & Issues):4(4):252–259.

3. Arceo-Vacas JL (2006). La investigación de relaciones públicas en España. Anàlisi: Quaderns de comunicació i cultura (34):111–124.

4. Avery EJ, Lariscy RW, Kim S, Hocke T (2010). A quantitative review of crisis communication research in public relations from 1991 to 2009. Public Relations Review, 36(2):190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.01.001

5. Avery E, Lariscy R, Amador E, Ickowitz T, Primm C, Taylor A (2010). Diffusion of Social Media Among Public Relations Practitioners in Health Departments Across Various Community Population Sizes. Journal of Public Relations Research, 22(3):336–358.

6. Balima ST (2006). Comunicación para la salud en África: experiencias y desafíos. Comunicar: Revista científica iberoamericana de comunicación y educación, (26):21–26.

7. Brodie RJ, Glynn MS, Van-Durme J (2002). Towards a Theory of Marketplace Equity: Integrating Branding and Relationship Thinking with Financial Thinking. Marketing Theory, 2(1):5–28.

8. Cangelosi JD, Ranelli E, Markham FS (2009). Who is Making Lifestyle Changes Due to Preventive Health Care Information? A Demographic Analysis. Health Marketing Quarterly, 26(2):69–86. doi: 10.1080/07359680802619776

9. Casetti F, Di-Chio F (1999). Análisis de la televisión: instrumentos, métodos y prácticas de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós.

10. Castiel LD, Álvarez-Dardet C (2005). Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en salud pública: las precariedades del exceso. Revista española de salud pública, 79(3):331–337.

11. Castillo-Esparcia A (2006). Las relaciones públicas internas como factor de gestión empresarial. Anàlisi: Quaderns de comunicació i cultura, (34):193–208.

12. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. (2012). Barómetro sanitario 2012 (total oleadas). Recuperado el 15 de septiembre de 2015 de http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=14096

13. Costa-Sánchez C (2012). El gabinete de comunicación del hospital. Propuesta teórica y acercamiento a la realidad de los departamentos de comunicación de los hospitales públicos de Galicia. Doxa Comunicación: revista interdisciplinar de estudios de comunicación y ciencias sociales. Universidad San Pablo-CEU.

14. Del-Pozo-Irribarría J, Ferreras-Oleffe M (2011). La telefonía móvil como instrumento de comunicación para la información y prevención del consumo de drogas. In In Cuesta-Cambra U, Menéndez-Hevia T, Ugarte-Iturrizaga A (Eds.), Comunicación y salud: nuevos escenarios y tendencias (pp. 111–123). Madrid: Editorial Complutense.

15. Díaz HA (2011). La comunicación para la salud desde una perspectiva relacional. In Cuesta-Cambra U, Menéndez-Hevia T, Ugarte-Iturrizaga A (Eds.), Comunicación y salud: nuevos escenarios y tendencias (pp. 33–49). Madrid: Editorial Complutense.

16. Eggener S (1998). The power of the pen: Medical journalism and public awareness. Journal of the American Medical Association, 279(17):1.400.

17. Elías C (2000). Flujos de información entre científicos y prensa. Universidad de La Laguna.

18. Freberg K, Palenchar MJ, Veil SR (2013). Managing and sharing H1N1 crisis information using social media bookmarking services. Public Relations Review, 39(3):178–184.

19. Gbadeyan RA (2010). Health Care Marketing and Public Relations in Not for Profit Hospitals in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(7):117–125.

20. Gordon CG, Kelly KS (1999). Public Relations Expertise and Organizational Effectiveness: A Study of U.S. Hospitals. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11(2):143–165. doi: 10.1207/s1532754xjprr1102_03

21. Grunig JE (1984). Organizations, environments, and models of public relations. Public Relations Research & Education, 1(1):6–29.

22. Grunig JE (1992). Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management (2nd ed.). Hillsdale (New Jersey): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

23. Gudykunst WB, Kim YY (1992). Communicating with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication. New York: McGraw-Hill.

24. Guth DW, Marsh C (2000). Public Relations: A Values-Driven Approach. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

25. Guy B, Williams DR, Aldridge A, Roggenkamp SD (2007). Approaches to organizing public relations functions in healthcare. Health Marketing Quarterly, 24(3-4):1–18. doi: 10.1080/07359680802118969

26. Hainsworth BE, Wilson LJ (1992). Strategic program planning. Public Relations Review, 18(1):9–15.

27. Henderson JK (2005). Evaluating public relations effectiveness in a health care setting. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 28(1-2):282–321.

28. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M (2005). Hospital performance reports: Impact on quality, market share, and reputation. Health Affairs, 24(4):1.150–1.160.

29. Iconoce. (2014). Conócenos. Recuperado el 21 de octubre de 2014 de http://info.iconoce.com/servicios.php

30. Igartua-Perosanz JJ (2006). Comunicación para la salud y sida: la aproximación educación-entretenimiento. Comunicar. Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 26, 35–42.

31. Instituto de Información Sanitaria. (2009). Estadística de establecimientos sanitarios con régimen de internado. Indicadores hospitalarios. Evolución 2000-2008. Recuperado el 1 de septiembre de 2015 de https://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/Evolutivo_2000-2008.pdf

32. Instituto de Información Sanitaria. (2013a). Estadística de centros sanitarios de atención especializada. Recuperado el 1 de septiembre de 2015 de http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estHospiInternado/inforAnual/homeESCRI.htm

33.Instituto de Información Sanitaria. (2013b). Notas metodológicas del Barómetro Sanitario. Recuperado el 3 de septiembre de 2015 de https://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/BS_2013/BS_2013Metodologia.pdf

34. Instituto de Información Sanitaria. (2013c). Ficha técnica del Barómetro Sanitario. Recuperado el 1 de septiembre de 2015 de https://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/BS_2013/BS_2013FichaTecnica3oleadas.pdf

35. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2012). Cuentas Económicas. Contabilidad Regional de España. Base 2008. Recuperado el 25 de marzo de 2015 de http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t35/p010&file=inebase&L=0

36. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2013). Padrón municipal. Recuperado el 25 de marzo de 2015 de http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t20/e260&file=inebase&L=0

37. Ivanov B, Sims JD, Parker KA (2013). Leading the Way in New Product Introductions: Publicity’s Message Sequencing Success With Corporate Credibility and Image as Moderators. Journal of Public Relations Research, 25(5):442–466. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2013.795862

38. Jiménez-Pernett J, Olry-de-Labry-Lima A, García-Gutiérrez JF, Salcedo-Sánchez M (2009). Estudio sobre salud en Internet para adolescentes y jóvenes en la ciudad de Granada. In del-Pozo-Irribarría J, Pérez-Gómez L, Ferreras-Oleffe M (Eds.), Adicciones y nuevas tecnologías de la información y de la comunicación: perspectivas de su uso para la prevención y el tratamiento (pp. 95–102). Logroño: Gobierno de La Rioja: Consejería de Salud y Servicios Sociales.

39. Keller AC, Bergman MM, Heinzmann C, Todorov A, Weber H, Heberer M (2014). The relationship between hospital patients’ ratings of quality of care and communication. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 26(1):26–33. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt083

40. Kelly KS (1994). Fund-raising encroachment and potential of the public relations department in the nonprofit sector. Journal of Public Relations Research, 6, 1–22.

41. Kirdar Y (2007). The Role of Public Relations for Image Creating in Health Services: A Sample Patient Satisfaction Survey. Health Marketing Quarterly, 24(3-4):33–53. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07359680802119017

42. Kreps GL (2008). Strategic use of communication to market cancer prevention and control to vulnerable populations. Health Marketing Quarterly, 25(1-2):204–216. doi: 10.1080/07359680802126327

43. Kreps GL, Bonaguro EW, Query JL (1998). The history and development of the field of health communication. In Duffy BK, Jackson LD (Eds.), Health communication research: A guide to developments and directions (pp. 1–15). Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood Press.

44. Kreps GL, Kunimoto EN (1994). Effective communication in multicultural health care settings. Newbury Park (California): Sage Publications.

45. Kurtz HP (1969). Public Relations for Hospitals. Springfield (Illinois): Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

46. Lariscy RW, Avery EJ, Sohn Y (2010). Health Journalists and Three Levels of Public Information: Issue and Agenda Disparities? Journal of Public Relations Research, 22(2):113–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10627260802640708

47. Len-Ríos ME, Hinnant A, Park SA (2009). Understanding how health journalists judge public relations sources: A rules theory approach. Public Relations Review, 35(1):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.019

48. Lozano-Rendón JC (2007). Teoría e investigación de la comunicación de masas. México: Pearson Educación.

49. Lupiáñez-Villanueva F (2009). Internet y salud: una aproximación empírica a los usos de Internet relacionados con la salud. In del-Pozo-Irribarría J, Pérez-Gómez L, Ferreras-Oleffe M (Eds.), Adicciones y nuevas tecnologías de la información y de la comunicación: perspectivas de su uso para la prevención y el tratamiento (pp. 103–118). Logroño: Gobierno de La Rioja: Consejería de Salud y Servicios Sociales.

50. Meath M (2006). Taking time to care: best practices in long-term care communications. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 11(4):336–352. doi: 10.1108/13563280610713833

51. Menéndez-Prieto MD, Vadillo-Olmo FJ (2010). El plan de comunicación hospitalario: Herramienta de gestión sanitaria (p. 115). San Vicente (Alicante): Editorial Club Universitario.

52. Ministerio de Sanidad, S. S. e I. (2013). Catálogo Nacional de Hospitales 2013. Recuperado el 28 de junio de 2015 de http://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/prestaciones/centrosServiciosSNS/hospitales/docs/CNH2013.pdf

53. Observatorio de la Comunicación Científica. (2008). Medicina y salud en la prensa diaria. Informe Quiral 10 años. Barcelona. Recuperado el 7 de septiembre de 2014 de http://www.upf.edu/pcstacademy/_docs/Quiral10.pdf

54. Palencia-Lefler M (2011). 90 Técnicas de comunicación y relaciones públicas (Vol. Segunda, p. 528). Barcelona: Profit Editorial.

55. Pew Research Center for The People and the Press. (2004). Online news audience larger, more diverse: News audiences increasingly politicized. Washington, DC.

56. Pham HH, Coughlan J, O’Malley AS (2006). The impact of quality reporting programs on hospital operations. Health Affairs, 25(5):1412–1422.

57. Rodríguez-Breijo V (2009). Nuevos retos para el estudio de los efectos de los medios de comunicación. Madrid: Comunicación del XI Foro Universitario de Investigación en Comunicación.

58. Roessler P (2007). Public health and the media - A never-ending story. International Journal of Public Health, 52(5):259–260. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-0226-1

59. Roessler P (2007). Public health and the media – a never-ending story, 52, 259–260. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-0226-

60. Rojas-Orduña OI (2008). Relaciones públicas: La eficacia de la influencia. Madrid: Escuela Superior de Gestión Comercial y Marketing, ESIC.

61. Scott J, Vojir C, Jones K, Moore L (2005). Assessing nursing homes’ capacity to create and sustain improvement. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 20(1):36–42.

62. Springston JK, Champion VL (2004). Public relations and cultural aesthetics: designing health brochures. Public Relations Review, 30(4):483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2004.08.005

63. Springston JK, Weaver-Lariscy RA (2005). Public Relations Effectiveness in Public Health Institutions. Journal of health and human services administration, 28(1/2):218–245.

64. Sriramesh K (1991). The impact of societal culture on public relations: An ethnographic study of south Indian organizations. University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland.

65. Thomas RK (2005). Marketing Health Services (p. 469). Health Administration Pr.

66. Viswanath K (2006). Public communications and its role in reducing and eliminating health disparities. In Thompson G, Mitchell F, Williams M (Eds.), Examining the health disparities research plan of the national institutes of health: Unfinished business (pp. 215–253). Washington D.C.: National Academies Press.

67. Weaver-Lariscy R, Springston JK (2007). Health crises and media relations: Relationship management-by-fire. Health Marketing Quarterly, 24(3-4):81. doi: 10.1080/07359680802119066

68. Wilcox DL, Cameron GT, Xifra J (2007). Relaciones públicas: estrategias y tácticas (Vol. 8a , últim, pp. XXXI, 783; 775–778). Madrid etc.: Pearson Educacion.

69. Wimmer RD, Dominick JR (1996). La investigación científica de los medios de comunicación: una introducción a sus métodos. Barcelona: Bosch.

70. Wrenn B (2002). Contribution to Hospital Performance. Journal of Hospital Marketing &, 14(1):3–13.

71. Xifra J (2007). Técnicas de las relaciones públicas. Editorial UOC.

72. Xifra J (2008). Las relaciones públicas. Revista Latina de comunicación social (pp. 392–399). Barcelona: Ediciones UOC. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-63-2008-789-392-399

73. Youmans SL, Schillinger D (2003). Functional health literacy and medication use: the pharmacist’s role. The Annals of pharmacotherapy, 37(11):1726–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D070